OK, it’s only fair to call him by his full title, Edward, 2nd Duke of York. But, for the purposes of this article, he wasn’t Duke of York yet; his father died in 1402. So, during most of Richard II’s reign he was the Earl of Rutland, and for a short time, from 1397-1399, he was Duke of Aumale (or Albermarle). Of course, that came to an end after Richard’s deposition. How much did he contribute to his king’s downfall?

Edward was undoubtedly Richard’s favorite. It was even rumored that the king was considering announcing Edward as his heir, which would have shoved Henry Bolingbroke and Edmund Mortimer aside. The king certainly showered his cousin with titles and responsibilities; Edward was admiral of the northern fleet, constable of Dover castle, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, constable of the Tower, and Lord of the Isle of Wight. And these were just some of his greatest honors. On the down side, he was obliged to do much of the king’s dirty work, such as being held responsible for dispatching the Duke of Gloucester (to put it judiciously). Even that didn’t really come to light until after Richard’s deposition, though a few insiders knew about it.

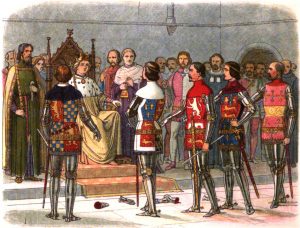

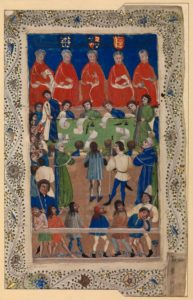

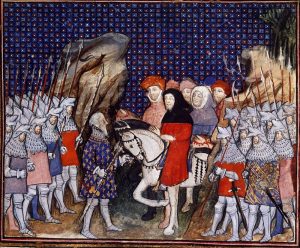

When Richard decided to wreak revenge on the three senior Lords Appellant he recruited his most intimate followers to accuse them; historians have called them the Counter-Appellants. Rutland was among their number. During the Revenge Parliament of 1397, Richard Earl of Arundel, Thomas Duke of Gloucester, and Thomas Earl of Warwick were convicted of treason for their actions during the Merciless Parliament ten years previously. Warwick’s death sentence was remitted because he begged for mercy, but the other two were not so lucky. After a lively defense Arundel was dragged off to the scaffold, and the Duke of Gloucester died in prison—after he wrote a confession. Was he murdered? Most everyone thought so, but who was going to accuse the king? It was much easier to point to the finger at Richard’s accomplices.

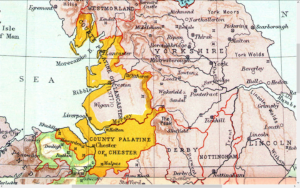

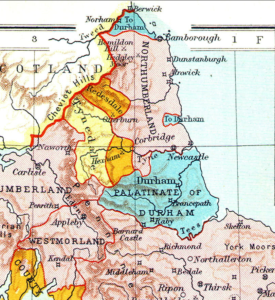

Most of the Counter-Appellants were given new titles; all were rewarded with lands forfeited by the traitors. Rutland was doing pretty well for himself. He had just been appointed Warden of the West Marches toward Scotland and was busy doing his duty when the king crossed over to Ireland on his second expedition. For the first few weeks, Richard looked anxiously for his cousin; Edward was running very late. When he finally showed up in Dublin, Rutland claimed he had needed more time to ensure that the Scottish border was quiet. Was this really the case, or was he up to something suspicious? No one knew for sure. But shortly after Edward’s arrival, Richard received word of Henry Bolingbroke’s invasion, which threw him into a panic. The king was all for dropping everything and immediately returning to England, but Rutland was the main dissenter to this plan; they needed time to reorganize the troops, and recall the scattered ships. Why not send the Earl of Salisbury ahead to gather an army in Cheshire and North Wales, and the king could join him later? Let Richard return via Milford Haven in South Wales and join the Duke of York—the acting regent—who was planning to wait for him in Bristol. Then together they could march north and join forces with Salisbury.

Reluctantly, Richard agreed to his suggestion, which turned out to be an utter disaster. Unbeknownst to him, the Duke of York had already gone over to Bolingbroke. There was no army waiting for the king in the south. In fact, he was denied entrance to Bristol altogether. Worse than that, Salisbury was unable to hold his recruits together for as long as it took Richard to get to Conway. Of course, the king didn’t know that, either, until it was too late.

As soon as Richard landed at Milford Haven with as many ships as he could muster—more were still to come—his army started to desert. Attempts to recruit more Welshmen failed miserably, and once Richard discovered that York had abandoned his cause, he decided to make a dash for Conway and Salisbury’s army. He traveled along the coast of Wales, accompanied by only a handful of men in an attempt to disguise himself and move as quickly as possible. Edward stayed behind to take command of the forces that were left. Apparently Richard still trusted him.

Later, it was reported that Rutland had received a letter from his father, telling him that all was lost and that he had changed sides. This would certainly account for the sudden reversal, for the morning after Richard disappeared, Rutland and Thomas Percy—steward of the royal household—announced the king’s abandonment to the army. In tears, Percy disbanded the royal household and broke the baton of office. Richard’s army dispersed and Rutland and Percy rode north and joined Bolingbroke.

This was Richard’s worst betrayal and he afterwards suspected Rutland of collusion all along. Did Edward intentionally give him bad advice in Ireland, thus stalling him and giving the Duke of York enough time to change sides? No one ever knew.