Bolingbroke’s decision to go for the crown has puzzled historians for the last 600 years. Certainly his contemporaries were led astray by his declaration that he was only returning from exile to recover his inheritance. Or were they? Many of them probably were—at first. After all, an outlaw ran the risk of losing his head if caught returning illegally, and anyone supporting him ran the same risk. So when Bolingbroke landed at Ravenspur around July 4, 1399 accompanied by a small but faithful retinue, the outlawed Archbishop of Canterbury, and the son of the executed Earl of Arundel, all were fair game to any loyalist looking to stop them. Nonetheless, the insistence that he was only seeking to regain his Lancastrian patrimony garnered a tremendous amount of sympathy from anyone who had something to lose. No one was safe from a king who could destroy their inheritance on a whim. But landowners weren’t the only ones who worried about their status. All Lancastrian retainers and servants stood to lose their positions. They could expect to find themselves replaced by vassals of new royal appointees who were to manage the estates until Bolingbroke’s eventual return—if he was ever allowed back.

Henry wasn’t about to let that happen. Once Richard left the country for Ireland, the time was ripe for Lancaster’s return. The first big encounter—and it happened very soon after Bolingbroke’s landing—was with Sir Harry Percy, known as Hotspur, the son of Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland. This happened at Bridlington, a town about thirty miles north of Ravenspur on the coast. His appearance was a big surprise, and if he had been so inclined, Bolingbroke’s expedition could have come to a screeching halt. But he was not so inclined. Over the last several years, Richard II had been steadily attempting to diminish the Percies’ influence in the North by removing them from key positions, and they were already disgruntled. They were quick to anticipate a golden opportunity—even though Henry assured Hotspur that he only wanted his inheritance back. Did they believe him, or were they already thinking ahead?

And so it began. Bolingbroke quickly garnered more support from the Northerners, making a wide berth around York and stopping off at Pontefract, his family’s stronghold. By now he was sure of his strength and moved on to Doncaster, where he met the earls of Northumberland and Westmorland among many other powerful local magnates. Northumberland had brought with him a large contingent—some said 30,000 men—which gave Bolingbroke the army he needed to challenge the royalist forces. In a very public ceremony he swore an oath that he had only returned to claim his inheritance, and did not have any designs on the crown. This wouldn’t be the last oath he was to make before changing his mind. It’s more than probable that at this point he also declared his intention to put the king under their control and impose a continual council, as they had in 1386.

Did his followers believe him? Historians conjecture that even if Henry had already decided to go for the crown (some think he did even before he landed, though there is no solid evidence), it was too soon to declare his intentions to a guarded populace. They had just barely recovered from Richard’s recent burst of tyranny; would they be willing to expose themselves to another series of threats? But if Bolingbroke came to assert his own rights, unfairly trampled upon, surely this was not treason?

And so, bolstered by a strong army that grew as he marched south, Bolingbroke solidified his credibility when he convinced the regent, Richard’s uncle the Duke of York, to come over to his cause. All along the regent was sympathetic to Henry’s grievances and was seriously distressed by this conflict of interest. After all, he was Henry’s uncle, too. Once again, it is thought that Bolingbroke repeated the same oath to York, convincing him to change sides.

The first action Bolingbroke took that indicated a possible change of intention came along shortly thereafter when they subjugated Bristol and executed three of King Richard’s close advisors—an action quite illegal unless ordered by the king. Afterwards, on their way north to Chester, he appointed Percy Warden of the West Marches toward Scotland—another custom reserved for the king. Yet still, Bolingbroke professed that he had no designs on the crown.

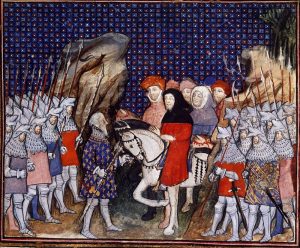

When Percy was chosen to approach King Richard who was by then holed up at Conwy Castle, again it was said that Henry swore the same oath. Did Percy really believe him? He certainly repeated this oath to Richard over a consecrated host, convincing the king to meet Bolingbroke in person. Too bad for Richard! He hadn’t traveled far from his sanctuary when Percy’s hidden soldiers surrounded him and and escorted his little party to Flint Castle, prisoners in fact. When meeting the humiliated king in person, according to the eye-witness Jean Creton, Henry said, “My Lord, I am come sooner than you sent for me: the reason wherefore I will tell you. The common report of your people is such, that you have, for the space of twenty or two and twenty years, governed them very badly and very rigorously, and in so much that they are not well contented therewith. But if it please our Lord, I will help you to govern them better than they have been governed in time past.” And Richard answered mildly, “Fair cousin, since it pleaseth you, it pleaseth us well.” If this wasn’t an acquiescence, I don’t know what more would have been needed!

The game was up, and although Bolingbroke treated the king like a prisoner, he still did not declare himself. With the king in tow, they all returned to Chester where Henry sent out summonses for a Parliament—in the king’s name—to be held the 30th of September. This would be about a month-and-half later. While in Chester, he received emissaries from London, who declared that the people renounced their allegiance to Richard and pledged their loyalty to Henry. It was said they even demanded that Henry put the king to death, but of course he refused. Three days later, Bolingbroke returned to London with his prisoner king, who rode a nag rather than his own horse, and was still dressed in the clothes he was wearing when arrested. When they reached London, Henry turned Richard over to the mayor and another delegation. By now the citizens must have come to their senses, because the officials escorted the king to the Tower, guarding him from the menacing crowd.

Richard was out of his hands. Now Bolingbroke could concentrate on finding a legal way to stage the deposition. By the time he reached London he had undoubtedly decided to go all the way.

Linda Boatwright says:

Very interesting read. I followed a link from Facebook and very glad I did.

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Thanks, Linda!

Alan Hurley says:

“Having sworn that he would not seize the throne he soon came to realise that seizing the throne was the only practicable way out of the situation which his own and Richard’s actions had created. He then discovered that by making rebellion successful he had made it respectable, and for most of his reign he had to contend with the rebellion of others.” — John L. Kirby, ‘Henry IV of England’, 1970

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Love it! I’m sure if he had to do it over he might have reconsidered… Or would he have?