For a long time my only knowledge about Richard II came from Shakespeare. How typical! The great bard established many historical figures in our mind that didn’t match reality (how about Richard III?). I suspect he would have been amazed at how literally we took his memorable characters. So when I decided to take on King Richard, I thought of him as tragic, naturally. I also thought, before he came to a bad end, that he was flippant, arrogant, inconsiderate, and self-centered. It was a tribute to Shakespeare’s skill that I felt sorry for him at the end.

I’m still not sure why I needed to write his story, but thirty some-odd books’ worth of research later, I’m glad I made the journey. My conception of Richard changed along the way, and it’s still probably incomplete. He was a complicated character, and once I found out what Shakespeare left out, I was more amazed than ever.

Born in Bordeaux, Richard didn’t move to England until he was four; apparently he didn’t speak a word of English. He was the second son; his brother, England’s heir, died just before they left France. From what I understand, he did not grow up with a support group since his youth was spent in the household of a dying man—his father, the Black Prince. Crowned king at age ten, the lonely boy started out at a disadvantage. No child should have that kind of responsibility thrust upon him, even if he was only a figurehead. Did he realize he was a figurehead? Or did he take his responsibilities seriously? Since he alone had to face the ringleaders of Peasants’ Revolt at fourteen, I’d say the young king took on more than his share of authority. Did any of his elders give him credit when the crisis was over? It appears not; they were quick to blame him when it came time to suppress the aftermath. I imagine this was the beginning of his “attitude” toward his alleged advisors.

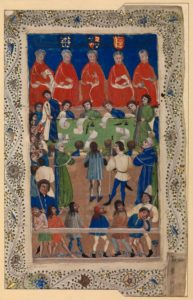

Not willing to suffer the reproaches from his council, he sequestered himself with the men he did trust: Sir Simon Burley, his tutor, Robert de Vere, his childhood friend from Edward III’s court, and Michael de la Pole, his chancellor, among others. These were the very men singled out for destruction by the Lords Appellant—led by the Duke of Gloucester and the earls of Warwick and Arundel. Once their patience ran out with Richard’s “bad government”, the Appellants decided it was time to clean house and get the king under their control (more of this in A KING UNDER SIEGE). As far as the Appellants were concerned, Richard was badly advised by his friends; they had to be eliminated—permanently. To say that the Lords were thorough would be an understatement! By the time the Merciless Parliament was over, Richard had lost his inner circle of friends to either judicial murder or outlawry, and his household members were all dismissed. The reins of power were wrested from his hands. His humiliation was complete. One can only imagine what that trauma would do to a young mind.

So, in 1389 when Ricard declared his majority at age twenty-two, he was a changed man. In fact, for the next seven years he behaved himself so well that everyone thought he had learned his lesson. It was a rare time of peace and prosperity. Chroniclers had nothing to talk about except the weather. Richard had proven that he knew how to rule well. Alas, when Queen Anne died in 1394, he lost his only remaining attachment from his youth. Theirs was a love match and he was devastated. Was she responsible for keeping him under control? When her restraining hand was removed, did he give vent to the rage that was simmering inside? It’s tempting to think so.

But he didn’t strike back until three years later. Historians are in disagreement as to the catalyst, but by 1397 he arrested the three original Lords Appellant and tried them for treason. One was his uncle, the Duke of Gloucester; the other two were the Earls of Arundel and Warwick. These arrests came as a complete surprise to everyone except his new circle of friends, soon known as the Counter-Appellants. All three Appellants were soon dead, and the other two, Henry Bolingbroke and Thomas de Mowbray, had a sinking feeling they were next.

What drove Richard to these acts of revenge? Had he planned them for seven years, just waiting until the timing was right? Did he carry around this terrible hatred for years, which surely would poison the most rational mind? Or did new acts of lese-majesty by the Appellants (never proven) set him off on his destructive path? Nobody knows. What seems to be the case is that he was so terrified that the whole thing would happen again, he decided to launch a pre-emptive strike against his enemies. And when that wasn’t enough, he insisted on sworn oaths to uphold Parliament’s new laws, again and again. Even worse, seventeen southern counties and London were deemed complicit with the Appellants, and he required that they sue for pardons—except that fifty unnamed accomplices would be excepted. Nobody knew if they were among the fifty condemned traitors, and over five hundred immediately came forward to secure their clemency.

Ultimately, I see Richard as someone who never had a sense of security. On the one hand, he was able to instill loyalty with his close friends. Both his wives loved him. His court was among the most cultured in Europe; he patronized men of letters such as Geoffrey Chaucer and John Gower, as well as Oxford University. For the first seven years after he achieved his majority, he reigned quietly and efficiently. England experienced a rare time of peace and prosperity. Chroniclers had little to talk about except the weather. Then, all of a sudden, it seemed that his pent-up anger and frustration burst forth. His enemies, who had been lulled into a false sense of security, were unexpectedly arrested and tried for treason. For a few short months, the Wheel of Fortune raised him to the top. Alas, in the end, his retribution wasn’t enough and he didn’t know when to stop; he felt that the whole country was against him, and took measures accordingly. What would Richard require to feel safe again? I don’t think he ever found out.