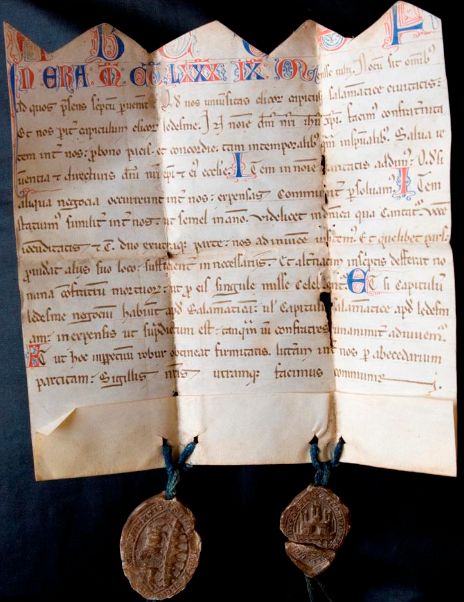

Put simply, an indenture was a contract written in two identical parts and divided irregularly—or indented—so that both halves could be joined together in the future. This post is mainly concerned with indentures made between King Henry V and his nobles for the invasion of France.

Funding an army was an intricate operation. An astonishing amount of paperwork has survived from the reign of Henry V, informing us of the exactitude practiced by the exchequer clerks. Several steps along the way guaranteed that every soldier was accounted for. But how were they paid?

For the most part, the king did not pay the soldiers directly. He would be responsible for his own household, as well as recruiting specialists such as gunners, 119 miners, 100 stonecutters, 120 carpenters and turners, 40 smiths, 60 waggoners, and the like (Anne Curry, 1415 Agincourt, p.71). For the rest, the nobles indented to bring a certain number of men-at-arms and archers with them. By now, the old feudal system had mutated into what many historians now call Bastard Feudalism, more of a fee-based agreement between the king and noble, or noble (I’ll call him the Captain) and his retainers (or retinue). For military service, the indenture might be drawn up for one year or less, depending on the plan of campaign. For the Agincourt campaign, the indentures were for twelve months.

So when the Captain applied his seal to the indenture, he was paid, up front, one half of the first quarter’s wages (the king having raised the money through taxes and loans). The second half of the first quarter would be paid at the muster, when the Exchequer’s officials actually counted the men to determine that everyone showed up. For the second quarter, because funds were short, the Captain was given jewels or some equivalent collateral to be redeemed at a future point (some were still outstanding in the reign of Henry VI). He was expected to pay the second quarter’s wages out of his pocket. The third quarter’s wages were supposed to be paid after six weeks of that quarter, and so on, though as the months progressed, things got a little messy.

But, as everyone knew, the real fortunes to be made would come from booty and, especially, ransoms. This, too, had a very specific breakdown. For anything worth more than ten marks, the Captain was entitled to a third share from every man in his retinue, regardless of rank. The king took a third part of the Captain’s gains, and a third of a third from each soldier and archer. Prisoners of certain rank, like dukes, would automatically get turned over to the king, and the soldier would expect some sort of compensation.

Men were recruited in a three-to-one ratio: three archers to each man-at-arms. The latter included earls, bannerets, and knights. The earls, knights, etc. that were recruited by the great dukes would in turn recruit the men-at-arms and archers. From what I can gather, many servants doubled as archers, but not all. Some household servants were directly paid by their masters, and were not in receipt of military wages. Those numbers are unknown. The greater the noble, the larger his contribution. The Duke of Clarence, Henry’s brother, indented for one earl, two barons, 14 knights, 222 esquires, and 720 mounted archers. The Duke of Gloucester, the next brother, brought 800 men total. After that, the numbers fell considerably; York and Arundel brought 400 each, Suffolk 160 and Oxford 140. Many of the knights indented directly with the Exchequer for somewhere between 40 and 120. So there were many small indentures, all of which had to be accounted for. The men were counted on their return, as well, including those invalided home after Harfleur.

Wages were calculated on a daily basis. A duke earned 13s 4d, an earl would get 6s 8d, a baron 4s, a knight 2s. an esquire 12d, and an archer 6d—this at a time when a skilled craftsman earned between 3d and 5d per day. So the incentive for archers was high. The king was responsible for shipping to and from France, including horses, harnesses, and supplies—another huge expense, when it is calculated that over 25,000 horses were needed for this campaign.

Each of the king’s copies of the indentures was kept in a drawstring pouch at the Exchequer with the Captain’s name on it. Any documentation that accrued during the campaign was added to the bag, such as muster rolls and wage claims. What a pile that must have been! Interestingly, since the Agincourt campaign ended before the third quarter began and many had been invalided home, the accounting was considerably complex. Some men were left behind to garrison Harfleur, and of course, there were those who had died during the siege or had been killed in the battle. Ultimately, the king decided to fix the start and end dates of the campaign, and even determined to pay the men who had been killed the full amount. This generosity was not forgotten, at least by the yeomen. The nobles, on the other hand, who had paid the second quarter in full, were shortchanged by the king’s decision to end the campaign forty-eight days early. It was left to them to petition Parliament for their loss. For some of the nobles, it was easier to compensate them with castles and land, and in some cases, admission to the Order of the Garter. Not everyone was happy, but who was going to complain to the hero of Agincourt?