A Palatinate (coming from palace) is one of those words bantered around that I never gave much thought to, until I realized how important it was. In Richard II’s reign, there were actually three Palatinates: Lancaster, Durham, and Chester. And what distinguished them from the rest of the country? They were nothing less than a kingdom inside of a kingdom, metaphorically speaking.

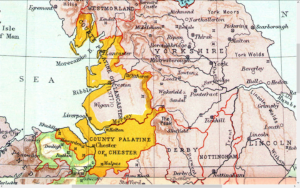

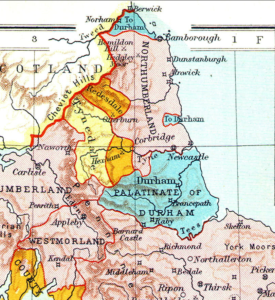

Palatinates date back to the Norman Conquest, and the earls and bishops, essentially, were given “princely” powers over their own jurisdictions — to help the king rule the marcher territories. Although other counties were given Palatinate powers, by the fourteenth century they had fallen into abeyance, leaving the big three. Durham was ruled by the Bishop of Durham. Lancaster (created in 1351) was ruled by the Duke of Lancaster, then united with the crown after Henry IV’s accession — though still administered separately. Chester was put under the control of the heir to the throne after Henry III, though Richard II promoted it to a Principality in 1398 (he entitled himself Prince of Chester). Henry IV returned it to a Palatinate in short order.

What does all this mean? It was put eloquently by James Wylie in his “History of England Under Henry the Fourth”: “…the County Palatine of Durham, which sent no representatives to the parliament at Westminster, but was governed by its own Prince Bishop, who exercised royal rights and jurisdiction, held his own courts, appointed his own judges, and might assert an actual independence when the central government was weak and distracted.” The Palatinate had its own chancery, its own seal, its own sheriffs and justices. Its own laws. Revenues stayed within the Palatinate. Bottom line: the king’s writ had no power there. Parliamentary representation came later: Chester in 1543; Durham in 1654, and Lancaster in 1873.

Needless to say, the Palatinate of Lancaster was a huge concern to Richard II. Although the Duke of Lancaster swore fealty to the king, Richard couldn’t touch much of his territory. The Palatinate encompassed Lancashire, but the duke also controlled other territories and castles as far north as Pickering (north Yorkshire) as far south as Pevensey, and as far east as Gimmingham, in Norfolk. These territories were the jurisdiction of the duke under the rule of the king. Nonetheless, when all put together, the Duke of Lancaster was the most powerful noble in the land, and if he chose to rebel, the strength from his Palatinate could present a formidable block.

The Palatinate was a gift from the king; John of Gaunt did not obtain its rule in Lancashire until 1377 (Edward III’s last Parliament), and this grant was only for life. However, in 1390, after achieving his majority, Richard II was so eager to bind his uncle to his cause that he awarded the Palatinate to Gaunt’s heirs male. It wasn’t until the king was firmly in control, seven years later, that he realized his serious error. He was no longer friendly with his cousin Henry of Bolingbroke—if he had ever been—and once Gaunt died there was every possibility that Henry would become a formidable threat. No king wanted that kind of challenger in his own backyard. This goes a long way toward explaining why Richard seized Bolingbroke’s inheritance after Gaunt’s death. What exactly he planned to do about it will never be known, for his usurpation followed a few months later.

When Henry IV became king, he chose to maintain the Duchy of Lancaster as a separate entity; he didn’t want the Duchy to be absorbed into the crown’s possessions. The Palatinate eventually morphed into a parcel of the Duchy and soon the same officers administrated both. This separate status of the Duchy of Lancaster lasted all the way until 1971.