Swegn was the eldest son of a prolific family. His father, Godwine of Wessex, worked his way up from relative obscurity to the most powerful Earl in the country. Swegn’s future could have been assured if only he had behaved himself and not acted like a rogue and an outlaw. He was the only one of his brood who seemed totally evil from the first. What happened?

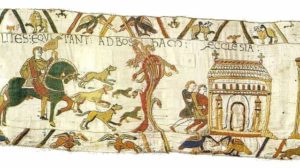

We know very little aside from the basic events which look very bad indeed. Initially Swegn held an important earldom which included Herefordshire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, and Somerset. In 1046, as he was returning from a successful expedition into Wales, he is said to have abducted the abbess of Leominster, had his way with her then sent her back in disgrace. For this deed he was exiled and lost his earldom.

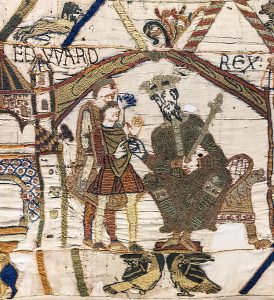

Swegn eventually submitted to the King and asked to be restored his lands. At first Edward agreed, but his brother Harold and cousin Beorn, who were given parts of Swegn’s divided earldom, refused to turn over their possessions. King Edward decided to accept their refusal and gave Swegn four days safe conduct back to his ships, anchored at Bosham.

At the same time, England was threatened by a Danish fleet; there was a lot of back and forth as Godwine and sons moved their ships to defend the Kentish coast. Threatened by severe weather, Godwine anchored off Pevensey and Beorn apparently searched him out there (to defend his actions?). Swegn did as well, and I assume there was some heated discussion before Beorn agreed to accompany his cousin back to the king and make amends. Reluctant to leave his own ships unsupervised any longer, Swegn persuaded Beorn to return to his home base at Bosham, from whence they would continue to King Edward at Sandwich.

Poor Beorn never made it to Sandwich. Once at Bosham, he was allegedly seized, bound, and thrown into a ship, where he was murdered by Swegn and his body dumped off at Dartmouth. Or possibly, Beorn and Swegn quarreled before the killing, which undoubtedly happened no matter what the cause. This time, Swegn had gone too far. Declared nithing (or worthless) by king and countrymen, Swegn was deserted by his own men and took refuge in Flanders.

Amazingly, the next year he was reinstated in his old earldom with the help of Bishop Ealdred, known as the peacemaker. But trouble was on the horizon (nothing to do with Swegn this time). In 1051 Eustace of Bologne created a huge ruckus in Dover then fled to the king complaining that he lost 21 men to the vicious townspeople. Taking advantage of the opportunity to assert himself, King Edward ordered Godwine to punish the offenders. The earl refused, putting himself on the wrong side of the law. The crisis escalated into an armed confrontation, with Godwine and Swegn cast as rebels. But no one wanted civil war, so Godwine backed down and was eventually driven into exile along with his family. Swegn accompanied his father to Flanders once again, but, overcome with remorse, continued to Jerusalem on a pilgrimage from which he never returned.

It’s easy to dismiss Swegn as the black sheep of the family. But perhaps his story goes a little deeper than that. First of all, consider the circumstances of Godwine and Gytha’s marriage. King Canute gave Godwine—a commoner—in marriage to this high-ranking Danish woman whose brother had recently been killed by Canute’s orders. This doesn’t sound like an auspicious beginning, and I wonder if the early years of their marriage weren’t a bit tempestuous. Perhaps their first son was born in the midst of bitter recriminations? This might explain Godwine’s stubborn defense of his wayward son in face of almost universal disapproval. It was reported that during his second banishment, Swegn put it about that King Canute was his real father, which caused Gytha to strenuously and very publicly object. What was the motivation behind this outrage?

The abbess of Leominster story has a possible explanation. There is circumstantial evidence Eadgifu may have been related to the late Earl Hakon, nephew of King Canute. She may possibly have been childhood friends with Swegn, and perhaps more; it doesn’t make sense for him to have kidnapped a high-profile total stranger. The Worcester tradition states that he kept her for one year and wanted to marry her, but was forbidden by the church and commanded to return her to Leominster, which caused him to leave the country.

As for Beorn, there seems little defense. It has been said that it was Harold rather than Beorn that stubbornly refused to release the territory to Swegn, and this is why Swegn was able to persuade Beorn to accompany him to the king in Sandwich. Perhaps Beorn wanted to please Godwine, his uncle-by-marriage, and agreed to negotiate. Regardless, Beorn must have been the victim of Swegn’s bad temper (at best) or revenge (at worst). Swegn’s decision to go on pilgrimage seems to have been the last attempt to redeem himself.

It is said that Swegn died on his way back from Jerusalem exactly fourteen days after Godwine’s successful return to England. By all reports, Swegn was mourned by no one except his father. No one was to know it yet, but this was the beginning of the end for Earl Godwine; he fell into decline and didn’t last out the year.

You can read more about this in my novel, GODWINE KINGMAKER.