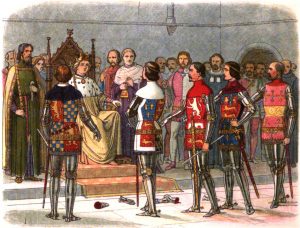

Being a medieval king came with all sorts of challenges, chief among them how to stop people from rebelling and in general causing unnecessary upheaval in your country. Sheesh: couldn’t they just accept that the one in charge was the king? Only the king? Clearly, something had to be done to keep people on the straight and narrow, which is why – or so the story goes – late in the 13th century, Edward I decided he needed to up the death-penalty somewhat, make it even more of a deterrent. Specifically, Edward I wanted people considering treason to think again – which was why, on October of 1283, he had the last Prince of Wales, Dafydd ap Gruffydd, subjected to horrific torture before the poor man finally died. Dafydd thereby became the first recorded person to be executed by the gruesome means of being hanged, drawn and quartered. I’m guessing Dafydd would have preferred being remembered for something else… It is still a matter of dispute whether Edward I is responsible for the introduction of this terrible punishment. There are indications Henry III, Edward’s generally rather mild father, condemned someone to die like this for an attempted assassination. I imagine that had Simon de Montfort not lost his life at Evesham, he’d have been a prime candidate for being the first ever nobleman to die thus. Fortunately (well relatively speaking: Montfort’s death was no walk in the park) Montfort did die on the battlefield, and so instead here we have Dafydd as the eternal poster boy for dying slowly and very, very painfully.

Being a medieval king came with all sorts of challenges, chief among them how to stop people from rebelling and in general causing unnecessary upheaval in your country. Sheesh: couldn’t they just accept that the one in charge was the king? Only the king? Clearly, something had to be done to keep people on the straight and narrow, which is why – or so the story goes – late in the 13th century, Edward I decided he needed to up the death-penalty somewhat, make it even more of a deterrent. Specifically, Edward I wanted people considering treason to think again – which was why, on October of 1283, he had the last Prince of Wales, Dafydd ap Gruffydd, subjected to horrific torture before the poor man finally died. Dafydd thereby became the first recorded person to be executed by the gruesome means of being hanged, drawn and quartered. I’m guessing Dafydd would have preferred being remembered for something else… It is still a matter of dispute whether Edward I is responsible for the introduction of this terrible punishment. There are indications Henry III, Edward’s generally rather mild father, condemned someone to die like this for an attempted assassination. I imagine that had Simon de Montfort not lost his life at Evesham, he’d have been a prime candidate for being the first ever nobleman to die thus. Fortunately (well relatively speaking: Montfort’s death was no walk in the park) Montfort did die on the battlefield, and so instead here we have Dafydd as the eternal poster boy for dying slowly and very, very painfully.  To be thus executed involved a lot of stages. First, you were tied to a horse (or in some cases several horses) and dragged through the town. Doesn’t sound too bad, you may think, but imagine being dragged over uneven cobbles, over gravel and stones, mud and slime, while the spectators lining the road pelt you with stuff – hard stuff, mostly. By the time the victim arrived at the gallows, he was a collection of bruises and gashes, his garments torn to shreds. Chances were, the man couldn’t stand, but stand he had to, and soon enough he was hoisted upwards, to the waiting noose.

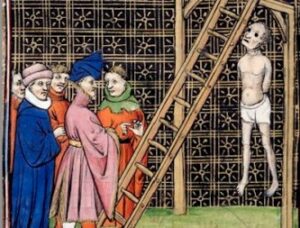

To be thus executed involved a lot of stages. First, you were tied to a horse (or in some cases several horses) and dragged through the town. Doesn’t sound too bad, you may think, but imagine being dragged over uneven cobbles, over gravel and stones, mud and slime, while the spectators lining the road pelt you with stuff – hard stuff, mostly. By the time the victim arrived at the gallows, he was a collection of bruises and gashes, his garments torn to shreds. Chances were, the man couldn’t stand, but stand he had to, and soon enough he was hoisted upwards, to the waiting noose.

The second stage involved the hanging as such. In medieval times, hanging rarely resulted in a broken neck. The condemned man didn’t drop several feet. Instead, the victim was set to swing from his neck and slowly strangled to death. A painful and extended demise, with the further indignity that when a man dies, his bowels and bladder give. However, the unfortunate sod who’d been condemned to being hanged, drawn and quartered, never got to the bladder and bowels part. He was cut down before he died and placed before the executioner and his big, sharp knife. The horror was just about to begin.

In some cases, the executioner started by gelding the man. Loud cheers from the spectators – or not, depending on who was being executed. Executions generally drew huge crowds, people standing about and snacking on the odd fritter or two while watching the condemned die. Nice – but hey, we must remember this was before the advent of TV and stuff like Counterstrike 4. People have always enjoyed being entertained with violence – which says a lot about the human race in general.

Once the condemned man had been relieved of his manhood (not something he’d ever use again anyway), he was cut open. A skilled executioner would keep him alive throughout the process, ensuring the dying man saw his organs being pulled from his body. And then, once the poor unfortunate finally expired, they chopped him up, sent off selected parts to be displayed in various parts of the kingdom, and buried what little was left over.

Not, all in all, a nice way to die. Men condemned to die that way must have swallowed and swallowed, knowing full well that no one could bear such indignities and die well. Before he drew his last breath, he’d have cried and wept, suffered horrific pain, hoped for the release of unconsciousness, only to be brought back up to the surface so as to fully experience what they did next to him. A truly demeaning death – most definitely a deterrent!

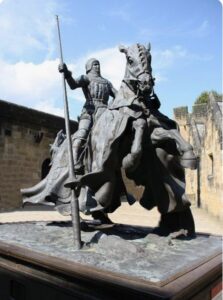

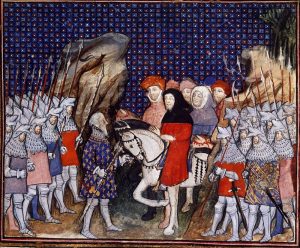

Edward I was quite fond of his new method of execution. Other than the unfortunate Dafydd, Edward had several Scottish “rebels and traitors” – in itself a strange label to put on men fighting for the freedom of their country – hanged, drawn and quartered, notably among them William Wallace and some of Robert Bruce’s brothers.

It is unlikely that any man subjected to such a gruesome death would be in a position to inhale and yell “FREEDOM!” as William Wallace does in Mel Gibson’s interpretation. It is far more likely that by the time the cutting began, the victim was in severe shock, incapable of uttering more than high-pitched shrieks and grunts.

The re were exceptions, though. Well at least if we’re to believe some of the “eye-witness” accounts that have made it down the centuries to us. Take, for example, the case of Thomas Blount, ond of the men who conspired to murder Henry IV and his young sons on Twelfth Night. The conspiracy failed, the rebels were brutally punished, and Thomas was drawn, hanged and was watching his entrails burn when he was asked by one of his guards if he needed a drink. Thomas Blount politely declined the offer, saying that he did not know where to put it…

re were exceptions, though. Well at least if we’re to believe some of the “eye-witness” accounts that have made it down the centuries to us. Take, for example, the case of Thomas Blount, ond of the men who conspired to murder Henry IV and his young sons on Twelfth Night. The conspiracy failed, the rebels were brutally punished, and Thomas was drawn, hanged and was watching his entrails burn when he was asked by one of his guards if he needed a drink. Thomas Blount politely declined the offer, saying that he did not know where to put it…

Back to Dafydd. He too, supposedly, died as well as one can die such a terrible death. No frantic screaming, no begging, although I imagine the poor man could not suppress the odd groan, gasp or whispered prayer.

My recent release, His Castilian Hawk, is set in Wales during those tumultuous years when Edward I crushed the Welsh underfoot. Below, a little excerpt detailing Dafydd’s final hours on this earth as seem through the eyes of my female protagonist, Noor, who has quite the dollop of Welsh blood running through her veins.

Excerpt:

They emerged into a cold and crisp autumn day. People were drifting in the direction of the castle, there were men-at-arms everywhere, and Noor shivered, pulling her cloak tight round her shoulders. A scaffold had been erected at the top of the slope that led to the castle. To the far right stood the church of St Mary; beyond the platform rose the walls of the castle, the royal banner unfurling in the wind.

“This is close enough,” Noor said, coming to a halt. To her surprise, Marured did not protest. She was rocking the babe, eyes lost in the bright blue sky above. Soon enough, they were hemmed in, Nicholas adopting a protective stance behind them. The majority of the spectators chattered and laughed; there were wineskins passed back and forth, pies and pasties shared.

Some stood silent, little groups of mostly men who looked grim and tired. Welshmen, Noor thought, biting back a surprised gasp when she recognised one of them as Rhys, one of the men who had accompanied Dafydd when he’d visited Orton Manor. Rhys inclined his head slightly in Noor’s direction before looking at Marured and lifting a hand in a greeting. She returned the gesture, flitting behind Noor so that she stood close to Rhys, her voice low and intense as she said something to him.

“Do you think Lord Robert is here?” Nicholas asked, narrowed eyes scanning their surroundings.

“Robert?” Noor stood on her toes, craning her neck as she turned this way and that, hoping for a glimpse of a familiar leather surcoat. “I wish—”

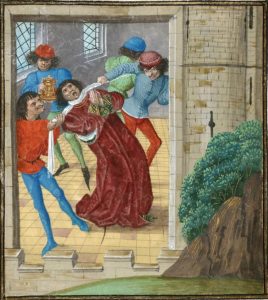

She was interrupted by a group of men-at-arms, yelling at them to make way, make way for the traitor. Behind them came a horse, and dragged behind it was a man. A roar rose from the assembled people. Eggs, stones, offal, rotten apples—the half-naked man tied to the horse was pelted from every direction.

“Dear God,” Noor whispered.

“This is but the beginning,” Nicholas muttered in response.

The horse was brought to a halt by the scaffolds. Two men-at-arms hauled Dafydd ap Gruffydd to his feet and ripped his tattered tunic from him. They made as if to manhandle him up the ladder, but he shook off their hands and climbed up on his own. Naked, dirty, bruised and bleeding, the former prince still carried himself with dignity.

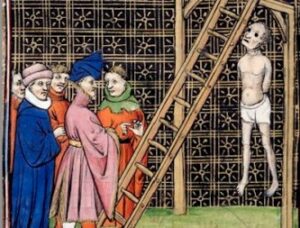

Dafydd stared straight ahead as a noose was placed round his neck. The executioner called out an order, and the rope was tightened. Noor did not want to look but could not tear her gaze away as the naked man was lifted off his feet. Limbs jerked, all of him shook, and Noor prayed and prayed that the executioner would miscalculate, thereby saving Dafydd from the coming indignities. One last twitch. The body hung still. The executioner barked instructions, the rope was released, and Dafydd tumbled onto the scaffold.

He hadn’t died. A staggering Dafydd was heaved up and tied to a ladder. The executioner held up a blade, and the mob bayed in response. From Marured came a strangled sob. From the man tied to the ladder came a high-pitched squeal, like the sound one of the pigs made when it was butchered. In difference to the pig’s squeal, this sound was abruptly cut short, as if the man being tortured had somehow regained control of himself.

Blood. So much blood. Dafydd sagged in his ropes, blood staining his upper thighs. The executioner held something up, and the crowd went wild. Marured wailed. One of the men beside her took hold of her and pulled her close.

Tied to his ladder, Dafydd was still alive. It was not over yet.

“Mother Mary, help him,” Noor groaned. “Give him strength in these his last moments.”

The crowd fell silent. When the executioner yet again approached Dafydd with the blade, Nicholas took hold of Noor and pressed her to his chest. She did not protest, hiding her face against the rough fabric of his tunic. It was as if all the assembled people held their breath, waiting. Other than the odd scuffing of shoes against the cobbles, it was so quiet she could hear her own breathing. Nicholas’ arm tightened round her. More silence, and then she heard Nicholas groan, “God save his soul.” The air filled with the faint scent of burning innards. But from Dafydd, there came not a sound, and some moments later the decisive sound of an axe cleaving flesh and bone had Noor crumpling, hot tears scalding her cheeks.

She straightened up. “May the Lord receive you into his kingdom,” she whispered, making the sign of the cross.

“Amen,” Nicholas said in a low voice. He shook himself. “Not even an accursed traitor deserves to die like that.” He nudged her and nodded in the direction of Marured, standing as if carved from stone some feet away. Her face was awash with tears, her gaze on the men still busy on the scaffold.

Rhys made the sign of the cross and muttered a soft, “Farewell, our prince.” He gestured for his companions to come with him, and they headed in the direction of the Welsh gate, a group of men who walked straight and unseeing, ploughing a path through the people still assembled. No one challenged them. Instead, they moved aside.

“He died well!” someone called out. The Welshmen came to a halt. Rhys turned in the direction of the speaker.

“All Welshmen know how to die,” he said. “It’s a lesson the English king has been kind enough to teach us over and over again.”

Amazon link: http://mybook.to/HISHAWK

MEET ANNA BELFRAGE:

Had Anna been allowed to choose, she’d have become a time-traveller. As this was impossible, she became a financial professional with two absorbing interests: history and writing. Anna has authored the acclaimed time travelling series The Graham Saga, set in 17th century Scotland and Maryland, as well as the equally acclaimed medieval series The King’s Greatest Enemy which is set in 14th century England.

More recently, Anna has published The Wanderer, a fast-paced contemporary romantic suspense trilogy with paranormal and time-slip ingredients. While she loved stepping out of her comfort zone (and will likely do so again ) she is delighted to be back in medieval times in her September 2020 release, His Castilian Hawk. Set against the complications of Edward I’s invasion of Wales, His Castilian Hawk is a story of loyalty, integrity—and love.

CONNECT WITH ANNA:

website www.annabelfrage.com

Amazon page, http://Author.to/ABG

FB: https://www.facebook.com/annabelfrageauthor/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/abelfrageauthor