Shakespeare touches on Harfleur in his famous play about Henry V, and I had always wondered what the significance of this siege was. Was it just a stepping-stone to Agincourt? Well, I discovered that the short answer is no. Agincourt was the unexpected battle; Harfleur was definitely on the agenda. When Henry launched his campaign in late summer of 1415, his destination was a well-kept secret. The French were so busy fighting their own civil war, he suspected they didn’t have the resources—or the incentive—to guard their coast against invasion. But of course, Henry couldn’t be sure. Only his pilots knew for certain where he was headed, but Harfleur was a good choice. Located at the mouth of the Seine, it had a strong walled port and was frequently used as a starting point for pirate raids and French attacks on England. Even better, the Seine led to Rouen and ultimately, Paris. Control of the Seine opened the way for many possibilities.

Initially, Henry V’s intention was to reclaim his patrimony in Normandy; many historians call it the Norman invasion in reverse. I don’t think he really took the concept of gaining the French crown seriously; it may have been in the back of his mind, but the actuality didn’t take place until many years later (I’ll cover that in my next book!). If you look at a map, you’ll see that the Seine pretty much cuts Normandy in half; this puts Harfleur as a port right in the middle of the dukedom. Henry envisioned it as a second Calais—which sits about 165 miles northeast. Since Harfleur is located on the north bank of the very wide Seine estuary, it was a logical jumping-off point for his invasion of Upper Normandy.

As usual, the invasion force got a late start, and they didn’t arrive in France until August 14. Henry chose to disembark at Chef-en-Caux (near modern Sainte-Adresse). It was a long beach before a tall chalk cliff, about three miles from Harfleur. Remnants of some defensive trenching had been long since abandoned, and no one was on hand to resist the English. It was certainly not conducive to unloading, and all the equipment (and horses) had to be offloaded to smaller vessels. It took three days to transfer the army and its supplies to land before they started their journey to Harfleur.

King Henry expected a siege and brought cannons and trebuchets, etc.to expedite the operation. He expected it to last only a couple of weeks, but the residents put up a stout defence and the English were tied down for six weeks, which brought them into late September. Worse than that, the army was stricken with dysentery, which put thousands of men out of action. By the end, between the twelve hundred soldiers left to garrison Harfleur, nearly two thousand invalided home, desertions, and untold deaths, the army was reduced by a third. He had somewhere between six and nine thousand men left (depending on the source) with which to continue, and winter was around the corner.

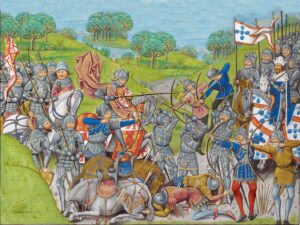

The king’s ambitious plan to continue his invasion had gone up in smoke, and even Henry’s declaration that he would travel overland to Calais before going home met with resistance. But to Henry, the capture of one little port town was not worth all the money and blood spent—all the grandiose promises and towering ambitions. No, he couldn’t go home now with his tail between his legs. It would seem like cowardice. At the very least, he wanted to see the land that he had decided to conquer. And so, overriding advice from more prudent men than himself, Henry took his undersized army along the coast to Calais, determined to follow the route of his great-grandfather Edward III.

Was he looking for a fight? Some would say that’s exactly what he hoped for.

But who would have predicted that the French would finally summon enough gumption to block his way at the famous ford at Blanche-Tacque? He was forced to march upstream several days along the Somme before finding a crossing, giving the enemy time to gather a huge army and confront him at Agincourt. His men had run out of food many days before, and they were exhausted, starving, and bedraggled. Most called his decision to march to Calais sheer folly, but the end result couldn’t have been more satisfying. Henry had his victory, and he proved that God was on his side.