Henry of Monmouth (so named because he was born at Monmouth Castle in Wales) was not his father’s favorite. That honor went to the next son Thomas, probably a year younger than him. It was said that young Henry was a bit aloof, and I suspect this had a lot to do with his father’s absence through much of his youth; Henry Bolingbroke spent many years galivanting around Europe and going on crusade. It’s kind of amazing he had any opportunity to beget so many children! Between 1386 and 1394 poor Mary de Bohun bore six children, dying while giving birth to her second daughter Philippa. The children were then raised by relatives.

When Bolingbroke was exiled in 1398, young Henry was surrendered as a hostage to King Richard II. Second son Thomas accompanied his father to Paris where—let’s face it—he had his sire all to himself. I suspect this accounted for Bolingbroke’s preference for him; could it be the first time he paid any real attention to his child?

Maybe I’m not being fair. Judging from the medications that were purchased for him, young Henry may have been a bit sickly. Thomas, on the other hand, was reportedly gregarious, good looking, and martially inclined. Very little was said in these early days about John, the next son born in 1389 and Humphrey, 1390. Their little sisters, Blanche (1392) and Philippa (1394) were married to foreign princes and don’t figure much in Henry’s story.

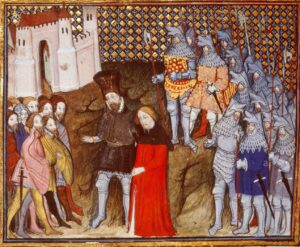

When young Henry was taken in by King Richard, his fortunes actually took a turn for the better. The childless king took a fancy to him, and it was even said that Richard saw future greatness in the boy. In many ways he treated Henry like the son he never had, took him to Ireland with him, and famously knighted him in the field. However, when word came to Ireland about Bolingbroke’s invasion, Henry was confined to Trim castle along with the heir of Buckingham for safekeeping. Apparently he didn’t resent the necessity, for the next time he saw Richard—after the king had been apprehended and imprisoned—Henry attempted to alleviate Richard’s discomfort. He was distressed by the usurpation, though not enough to refuse his elevation to Prince of Wales.

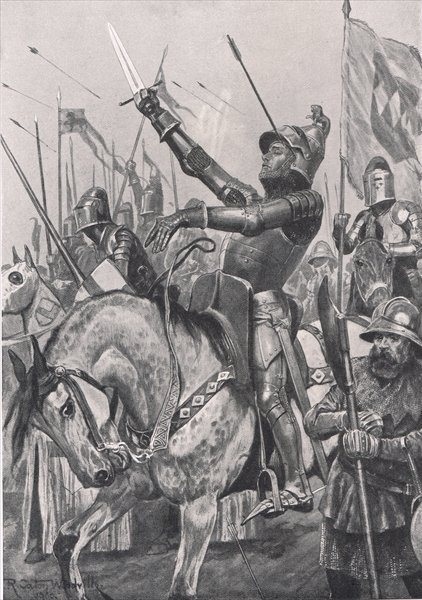

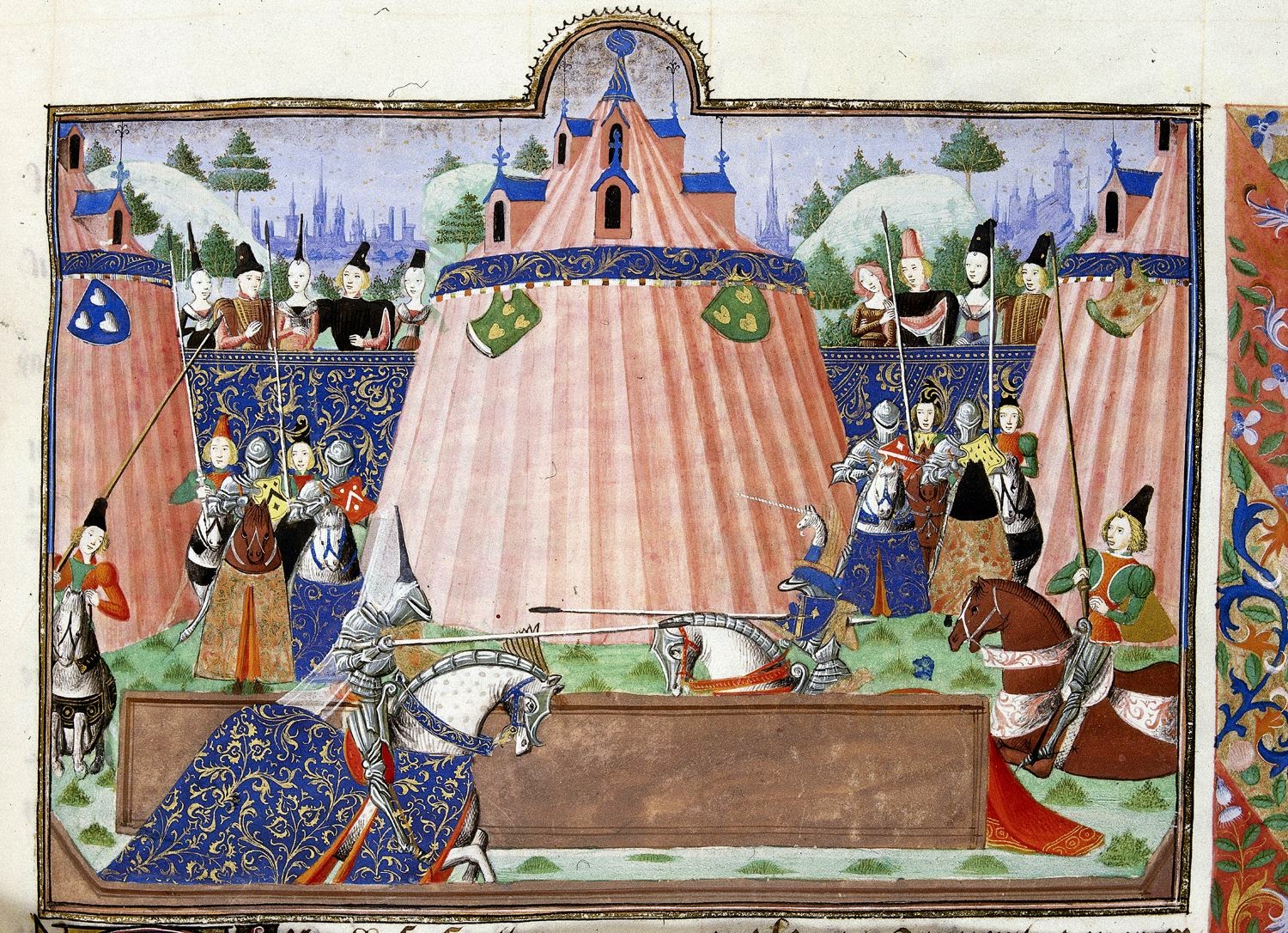

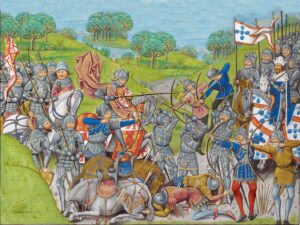

King Henry IV expected his sons to follow in his footsteps—at least as far as military and leadership training was concerned. Bolingbroke was a champion jouster as a young man, and took over governing the duchy of Lancaster when John of Gaunt campaigned in Spain and Aquitaine from 1386-89. Bolingbroke would have been 19 years old at the time. So after his new reign began, he had high expectations for his heir. The Welsh rose in rebellion during the first year after Bolingbroke took the crown, and Henry was put under the tutelage of Sir Henry “Hotspur” Percy at Conwy Castle. Unfortunately, Hotspur abandoned the cause after a couple of years in favor of his own rebellion. Within the year, Henry was given the lieutenancy of Wales, a major command and a lot of responsibility for a sixteen year-old. He would play a role in the Battle of Shrewsbury (1403) against his former mentor, taking an arrow in the face that nearly ended his life. That put him out of commission for about a year.

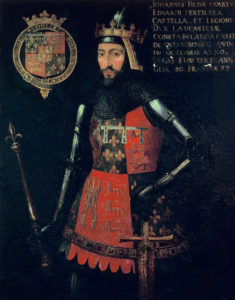

Meanwhile, his younger brother Thomas was sent to Ireland as lieutenant in 1402, an office he was to perform on and off—mostly off—for the next ten years. His salary was constantly in arrears and he hated the job, preferring something closer to home. His father preferred having him around, too, and didn’t object when he turned his responsibilities over to a second in command and came back to London. Although he was given the somewhat empty position of steward of England, he had no titles until the year before his father died, when he was made Duke of Clarence. This gave him the necessary prestige to command an invasion of France planned in conjunction with the Armagnacs against the Duke of Burgundy. Although this whole episode was a fiasco, since the French made peace and bought him off, Thomas got his first experience at least by heading a chevauché, the closest thing so far to actual combat.

John was next in line after Thomas, and Henry IV had plans for him as well. The young prince was sent to Northumberland under the tutelage of the Earl of Westmorland, whose rivalry with the Percies had reached a climax. Although Earl Henry Percy (Hotspur’s father) had survived the fallout from the Battle of Shrewsbury, his prestige and authority had greatly diminished in the region. John was appointed Warden of the East Marches toward Scotland—Hotspur’s former command. Westmorland was created Warden of the West Marches. This galled Percy to no end, and three years after Hotspur’s death, Percy launched an aborted rebellion against Henry IV. John accompanied Westmorland as they pursued and dealt with the rebels. John was destined to stay in the North all the way through the end of his father’s life; the experience would hold him in good stead when he would take over as regent during his brother’s reign.

This left Humphrey, who was only nine years old when Henry IV took the throne. Either his father ran out of jobs for him, or perhaps the king wanted to keep a son nearby, for Humphrey was stuck in the unenviable position of having nothing to occupy his talents. He was dragged along as the king moved about the country. Both Humphrey and John were young enough to benefit from the presence of Henry’s queen Joan of Navarre, who he married in 1403. Joan was obliged to leave her sons behind when she came to England, so she was ready to take the motherless boys under her wing. Now that Humphrey was the only son left at home, so to speak, he spent quite a lot of time with her. He wasn’t to make any major contribution to history until his brother became king.

Henry, as Prince of Wales, took his responsibilities very seriously—in contradiction to Shakespeare, who portrayed him as a good-for-nothing layabout, hanging around with drunks and thieves and causing trouble. The Welsh rebellion lasted nine years and Henry was in the thick of the fighting. He had no leisure to play around, and I don’t think he even spent much time in London. In 1410, as a result of his father’s failing health, Henry headed the Council in charge of the government. Unfortunately, he disagreed with the king on some fundamental political issues and he was dismissed a year later (there’s some question that he and his uncle Cardinal Beaufort may have tried to persuade King Henry to retire. If so, this backfired terribly.) His dismissal could have freed him up to go drinking with his buddies, but it wasn’t to last very long. King Henry IV died in March of 1413, and Henry V mounted the throne a changed man—allegedly.