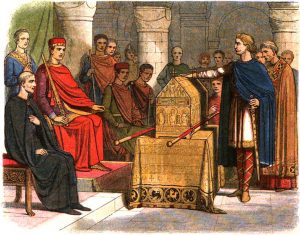

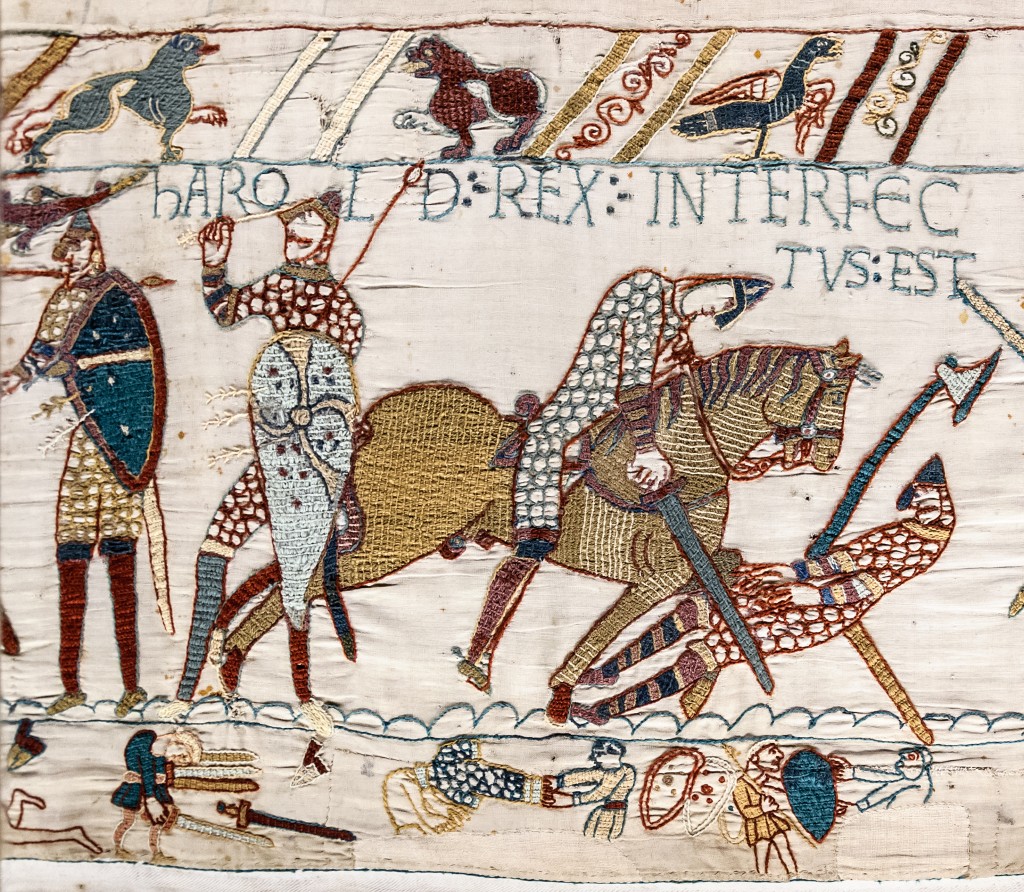

The Bayeux Tapestry gave us an iconic image of Harold pulling an arrow from his eye. It must be Harold: the name is embroidered around his head and spear. And since the Tapestry is created so close in time to the actual event, it is considered one of the major sources of documentation and hence to be trusted. But somehow, even the identification of the wounded hero is questioned by some, and further investigation raises more questions than it answers. Why?

The Bayeux Tapestry gave us an iconic image of Harold pulling an arrow from his eye. It must be Harold: the name is embroidered around his head and spear. And since the Tapestry is created so close in time to the actual event, it is considered one of the major sources of documentation and hence to be trusted. But somehow, even the identification of the wounded hero is questioned by some, and further investigation raises more questions than it answers. Why?

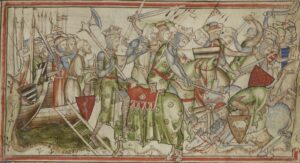

Well, one thread of discussion is the identity of the figure at Harold’s right, falling to the ground in the process of getting his leg cut off. As we learned from the 11th century Carmen de Hastingae Proelio, Harold was hacked up by four attackers (one of them might have been William). From 12th century Wace we learned that Harold was wounded in his eye by an arrow, then felled while still fighting, struck “on the thick of his thigh, down to the bone”. So many historians think the second figure is Harold. A third opinion is that both figures are Harold, since the Tapestry could be read like a long cartoon, where one scene leads to the next.

I recently learned about evidence that gives credence to the third theory, but only a close-up view will enlighten: a row of holes next to the second figure’s eye, that looks suspiciously like stitches that have been removed! An arrow? If so,  then clearly this is the same figure as the other. As historian David Bernstein tells us in a thoroughly investigated “The Blinding of Harold and the Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry”, there are three possible explanations for this row of holes: 1. They are traces of original stitches, which must have indicated an arrow above his eye (not in it). 2. Traces of an arrow sewn in by a later “inspired” restorer, that were subsequently removed by that person or someone else, or 3. Traces of an unrelated repair. Bernstein pretty much discards the third possibility. But what of #2?

then clearly this is the same figure as the other. As historian David Bernstein tells us in a thoroughly investigated “The Blinding of Harold and the Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry”, there are three possible explanations for this row of holes: 1. They are traces of original stitches, which must have indicated an arrow above his eye (not in it). 2. Traces of an arrow sewn in by a later “inspired” restorer, that were subsequently removed by that person or someone else, or 3. Traces of an unrelated repair. Bernstein pretty much discards the third possibility. But what of #2?

I should have realized that the Bayeux Tapestry was subjected to a few major restorations during its 900+ year-old existence. From what I can gather, it was restored in 1730, 1818, 1842 and most recently in 1982. It is recorded that the Victorian-era restorations are fairly easy to determine because the wool used for the embroidery left stains on the edges of the holes. But how many figures were altered considerably beyond their original form? And does Harold’s death scene count among the alterations? Sketches drawn by Antoine Benoît before the 18th century restoration do not indicate the row of holes next to the prone Harold’s eye, so it is apparent they might have been added later.

Bernstein tantalizingly reassured us in his manuscript that the 1982 restoration was bound to enlighten us through scientific analysis, but so far I haven’t been able to find the results of this event. Meanwhile, he gave us a theory as to why the Tapestry shows an arrow in the eye when not one of the six contemporary accounts mention it at all. He theorized that the arrow represented the hand of God in retribution for Harold’s oath-breaking. After all, the Tapestry was a Norman creation (propaganda tool?) and it is possible that William saw this supernatural intervention as an expression of God’s approval.