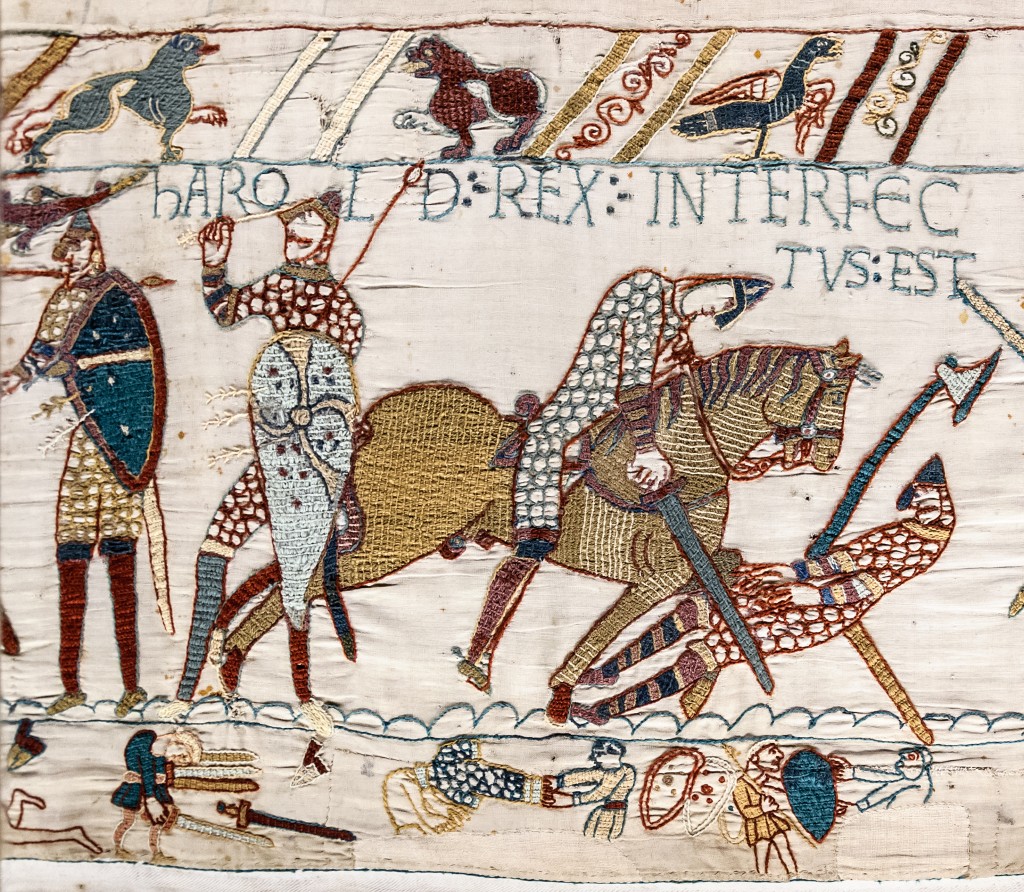

The Bayeux Tapestry gave us an iconic image of Harold pulling an arrow from his eye. It must be Harold: the name is embroidered around his head and spear. And since the Tapestry is created so close in time to the actual event, it is considered one of the major sources of documentation and hence to be trusted. But somehow, even the identification of the wounded hero is questioned by some, and further investigation raises more questions than it answers. Why?

The Bayeux Tapestry gave us an iconic image of Harold pulling an arrow from his eye. It must be Harold: the name is embroidered around his head and spear. And since the Tapestry is created so close in time to the actual event, it is considered one of the major sources of documentation and hence to be trusted. But somehow, even the identification of the wounded hero is questioned by some, and further investigation raises more questions than it answers. Why?

Well, one thread of discussion is the identity of the figure at Harold’s right, falling to the ground in the process of getting his leg cut off. As we learned from the 11th century Carmen de Hastingae Proelio, Harold was hacked up by four attackers (one of them might have been William). From 12th century Wace we learned that Harold was wounded in his eye by an arrow, then felled while still fighting, struck “on the thick of his thigh, down to the bone”. So many historians think the second figure is Harold. A third opinion is that both figures are Harold, since the Tapestry could be read like a long cartoon, where one scene leads to the next.

I recently learned about evidence that gives credence to the third theory, but only a close-up view will enlighten: a row of holes next to the second figure’s eye, that looks suspiciously like stitches that have been removed! An arrow? If so,  then clearly this is the same figure as the other. As historian David Bernstein tells us in a thoroughly investigated “The Blinding of Harold and the Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry”, there are three possible explanations for this row of holes: 1. They are traces of original stitches, which must have indicated an arrow above his eye (not in it). 2. Traces of an arrow sewn in by a later “inspired” restorer, that were subsequently removed by that person or someone else, or 3. Traces of an unrelated repair. Bernstein pretty much discards the third possibility. But what of #2?

then clearly this is the same figure as the other. As historian David Bernstein tells us in a thoroughly investigated “The Blinding of Harold and the Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry”, there are three possible explanations for this row of holes: 1. They are traces of original stitches, which must have indicated an arrow above his eye (not in it). 2. Traces of an arrow sewn in by a later “inspired” restorer, that were subsequently removed by that person or someone else, or 3. Traces of an unrelated repair. Bernstein pretty much discards the third possibility. But what of #2?

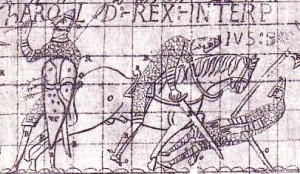

I should have realized that the Bayeux Tapestry was subjected to a few major restorations during its 900+ year-old existence. From what I can gather, it was restored in 1730, 1818, 1842 and most recently in 1982. It is recorded that the Victorian-era restorations are fairly easy to determine because the wool used for the embroidery left stains on the edges of the holes. But how many figures were altered considerably beyond their original form? And does Harold’s death scene count among the alterations? Sketches drawn by Antoine Benoît before the 18th century restoration do not indicate the row of holes next to the prone Harold’s eye, so it is apparent they might have been added later.

Bernstein tantalizingly reassured us in his manuscript that the 1982 restoration was bound to enlighten us through scientific analysis, but so far I haven’t been able to find the results of this event. Meanwhile, he gave us a theory as to why the Tapestry shows an arrow in the eye when not one of the six contemporary accounts mention it at all. He theorized that the arrow represented the hand of God in retribution for Harold’s oath-breaking. After all, the Tapestry was a Norman creation (propaganda tool?) and it is possible that William saw this supernatural intervention as an expression of God’s approval.

Kathleen Tyson says:

As I’ve spend the last 2 years obsessively re-transcribing and translating the 1067 Carmen, the earliest account of the Norman Conquest, this is a topic of great interest to me. The first mention of an arrow as a cause of death occurs in 1080 in the History of the Normans by Amatus of Monte Cassino, although it is repeated later by Wace. The Italian allies may have sought credit for the victory in England and exaggerated their contribution to the defeat of King Harold.

The Carmen gives a simpler account:

544. Heraldus cogit pergere carnis iter •

Harold is forced to go the way of all flesh.

545. Per clipeum primus dissolvens cuspide pectus •

The first shatters his breast through the shield by lance;

546. Effuso maculat sanguinis imbre solum •

A vast torrent of blood stains the ground.

547. Tegmine sub galeae caput amputat ense secundus •

The second by sword severs the head below the helmet’s cover.

548. Et telo ventris tercius exta rigat •

And the third by spear pours out the belly’s entrails.

549. Abscidit coxam quartus procul egit ademptam •

The fourth cuts off a leg at the hip.

From afar it urged withdrawal.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Carmen-Triumpho-Normannico-transcription-translation/dp/149270475X

I don’t buy that Bayeux Tapestry was made by women or by English manufacture. Norman men delighted in embroidery and it was customary for all men to sew and embroider in the 11th century, as sailors would continue to do for centuries after. It seems much more likely to me that the tapestry was the creation of Norman clerics.

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Hi Kathleen. Thanks for posting; this is so helpful! I can only add that in one of my many books, it was stated that the style and spelling of the Latin inscription showed an English influence, which is one of the reasons it is attributed to Anglo-Saxon seamstresses. I leave the conclusions to more studied heads than my own.

Kathleen Tyson says:

Cheers, Mercedes. The latin of the tituli is certainly very inferior to the quality of the best Norman abbeys. That would be consistent with Lanfranc’s disparagement of English abbeys where Latin was not as fluent. Then again the tituli may have been added later to re-tell the story to a later generation who did not live the events.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

Some spellings are Anglicisms, while others are peculiar to Normandy. This plus the presence of a Breton rebus and an English one suggests that the design was a collaboration.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

“The way of all flesh” is also a theme in Alan Rufus’s epitaph (August 1093). The poem is in Leonine hexameter and, though only seven couplets long, makes fascinating reading, with references to astronomy (twice), royalty (four times), England, Britain/Brittany (three times), Roman history and even ancient Iran, among other topics.

Gordon Grant says:

I was very interested in your post on the death of Harold and particularly in those needle holes which could suggest that Harold is represented as both the standing and the falling man. There is another feature of the falling figure that may be worth taking into account. Of the many soldiers depicted in the Bayeux tapestry wearing or wielding swords, about fifty wear their scabbards on the left side, so the right hand can draw the sword. In only four or five examples is the scabbard on the right, indicating a left-handed swordsman. Demographic authenticity seems an unlikely reason to include these few left handers, but perhaps it is significant that at least one of them is Harold. About a third of the way through the tapestry William and Harold fight together against Conan, Duke of Brittany. In gratitude for his help, William bestows arms upon his English ally in a scene where Harold wears his scabbard in the left-handed manner. So might it be of interest that the falling figure, too, is left handed? If the tapestry is intentionally showing Harold as left handed is it also, figuratively at least, implying he was ‘sinister’; a little less noble, and unworthy of the crown? Or perhaps it was simply known that Harold was indeed left handed.

Given the uncertainties created by successive restorations, the tapestry’s depiction of a man wearing the scabbard on his right side of his body might be just an error. Benoît’s drawing is hard to read (at least in reproductions), but Montfaucon, who had the Benoît version in front of him, made this figure a definite left-hander. For some reason Stothard’s version, though drawn from the tapestry itself, leaves the scabbard out altogether.

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Well, that is certainly an interesting observation! If you are correct, then the guy plucking the arrow out of his eye must not be Harold. I always thought it a bit odd that the “arrow” figure has a shield (and spear?) and the falling down guy has a two-handed axe. Very, very good catch; I never paid attention to right vs left handed.

Sharyn Furman says:

Mercedes, I’m now reading the third book in your series, Heir to a Prophecy. I’m totally enthralled by all three and look forward to more. We all have our historical theories, but in truth, this will never be proven beyond a shadow of a doubt. Truly, Harold was my king!!

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Thank you so much, Sharyn! Actually, HEIR TO A PROPHECY was my first novel, intended to be a stand-alone. It was while researching HEIR that I decided to write about the Godwines. Part 3 of the Trilogy is still to come: FATAL RIVALRY, due out by the end of this year! I would soooo appreciate a review in Amazon; in today’s world, this is an author’s life-blood!

Alex Meyer says:

What a great article thank you Mercedes

Sara Waterson says:

Since the two figures are so close together, I feel that if they were both intended to represent Harold they would have been shown in the same stockings. I haven’t however made a study of the tapestry to see whether this kind of consistency in detail is usual.

Mercedes Rochelle says:

I noticed the stockings, too. And, as Marc Morris pointed out, Harold would have had to exchange a shield for a Danish axe pretty quickly.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

Sara: Alan Rufus’s attire, horse and shields are depicted consistently throughout his fifteen or so appearances. The only real changes are between civvies (orange tunic, yellow v-neck and yellow belt) and battle dress (chain mail and helmet, naturally) and between his diplomatic shield (a heraldic animal) and his military shield (plain white with 12 points of rank).

Alan was a stickler for accuracy and he knew the Scolland family personally, so it’s possible he insisted on the Abbot getting his details correct.

Sylvette Lemagnen says:

No restoration in 1982!

Mercedes Rochelle says:

This isn’t where I got it, but a brief Google search turned up references to it. Here is one: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/540294/summary