Despite all the brouhaha back in 2014 about scanning the grounds of Waltham Abbey for the body of Harold, some prefer the more recent theory that he lies in one of four tombs under St Michael’s Church in Bishop’s Stortford, Herts. Or, if you like, there’s the fanciful conjecture that he survived the battle and lived in obscurity. I wonder if we might be looking in the wrong place altogether. Is it really possible that archaeologists can reproduce the unlikely discovery of yet another famous King killed in battle? It’s impossible to describe the miracle of discovering Richard III in a parking lot—to the uninitiated—without sounding completely ridiculous. I know; I tried it. And so far I haven’t heard of any likely Godwineson DNA descendant stepping forward to prove the case, even if they found a body.

Despite all the brouhaha back in 2014 about scanning the grounds of Waltham Abbey for the body of Harold, some prefer the more recent theory that he lies in one of four tombs under St Michael’s Church in Bishop’s Stortford, Herts. Or, if you like, there’s the fanciful conjecture that he survived the battle and lived in obscurity. I wonder if we might be looking in the wrong place altogether. Is it really possible that archaeologists can reproduce the unlikely discovery of yet another famous King killed in battle? It’s impossible to describe the miracle of discovering Richard III in a parking lot—to the uninitiated—without sounding completely ridiculous. I know; I tried it. And so far I haven’t heard of any likely Godwineson DNA descendant stepping forward to prove the case, even if they found a body.

The theory that Harold survived the battle and became a pilgrim comes from “novelist and amateur historian Peter Burke” according to BBC News, who found this reference in the 12th century Vita Harold. I located an 1885 copy and translation of this work on the (very useful) ForgottenBooks.com website and discovered the full title was “Vita Harold The Romance of the Life of Harold King of England.” Well, that says a lot, doesn’t it? After reading the first few pages of this manuscript, where King Knut, feeling threatened by Earl Godwine, sends him on a mission to Denmark with letters instructing the recipients to chop off his head, I got suspicious. Oh, and Godwine substituted that letter with one of his own, instructing the recipients to receive him with honor and give him Knut’s sister in marriage. To say the least, I concluded that this manuscript was not very reliable. And here’s another nail in that coffin: according to Emma Mason in her “The House of Godwine” history, by the time of Henry II, Waltham Abbey had converted to Augustinian canons who found the tomb-cult of Harold Godwineson distasteful. So they commissioned a cleric to write the Life of Harold to draw attention elsewhere. Hmmm.

On firmer ground, the association between Harold and Waltham abbey makes good sense. He is said to have been miraculously cured there as a child and rebuilt the abbey in 1060. There’s another reference to the Holy Cross at Waltham: the Christ figure on the cross allegedly bowed its head as Harold stopped there to pray before the Battle of Hastings. According to William of Malmesbury, William the Conqueror sent Harold’s body to his mother Gytha who had it buried at Waltham. According to the Waltham Chronicle, two canons from the Abbey begged William for Harold’s body and he consented; after enlisting the aid of Edith Swanneck they located the body and carried it back. Apparently there was a sepulcher erected to Harold after his death which attracted a cult following; the grave was relocated a few times, whenever the church was town down and rebuilt.

After the Dissolution of the monasteries, a manor house was erected from the rubble of the Abbey. Another story states that a “famous Bumper Squire Jones” was enlarging the cellar of said manor house when he discovered the coffin of Harold under a lid inscribed with Haroldus Rex. He kept the coffin in the cellar and showed it to his friends whenever he had a party. The house burned down not too long after and was demolished in 1770, presumably along with the coffin.

A persistent story from William of Poitiers states that William the Conqueror gave Harold’s body to his companion William Malet to bury under a pile of rocks on the Sussex coast, quipping that “he who guarded the coast with such insensate zeal should be buried by the seashore”. Our eminent historian Edward A. Freeman concluded that first they may have buried Harold under a cairn, only to remove him a few years later to a more proper grave at Waltham.

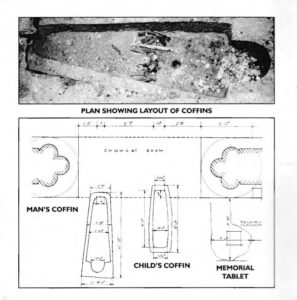

However, there is another possible explanation to the grave beside the sea. In 1954 during routine maintenance at Holy Trinity Church in Bosham, workers discovered a coffin under the paving stones near the chancel steps, just three feet from the second coffin already believed to contain the remains of Canute’s daughter. According to Geoffrey Marwood, local historian, “The large coffin was made of Horsham stone, magnificently furnished and contained the thigh and pelvic bones of a powerfully built man about 5 ft. 6 ins. in height aged over 60 years with traces of arthritis. Whoever was buried here must have been a person of great importance to have been placed in such a prominent position in the church…” This may be slim evidence except for the fact that Bosham was Harold’s home town and birthplace. Although Harold was 44 when he died, forensic evidence in the 1950s was not exacting; but they did determine that the bones showed fractures that did not have time to heal. The missing head and lower leg could argue for a body already dismembered in the way Harold was.

Bosham was the only estate in Sussex that King William took into his personal possession. It is unlikely that anyone could have been buried there without his knowledge, and the depth of the coffin under the floor implied that the gravediggers knowingly placed it at the same level as Canute’s daughter. It is possible that William consented to give Harold his place by the sea in the harbor town of Bosham; he didn’t want a local shrine to the fallen king, but he may have given him a proper burial in secret. Locals certainly choose to believe so.

super blue says:

Very good – one sentence more so than the rest. Richard is indeed the template for this case or Alfred or whoever.

Permission to re-blog?

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Please do! Many thanks for the interest

Bev says:

Thanks for such an enlightening article. I have been feeling a tad cynical about this dig but without access to the primary sources it was difficult to be certain that its likely to be a wild goose chase.

David says:

I know exactly where one of the sons of Harold is. The remains were dug up in the 1950s.

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Hi David. Which son is this?

Brook Allen says:

Way to research, Mercedes! Most impressive!

Geoffrey Tobin says:

Bosham is highlighted in scenes 2 and 3 of the Bayeux Tapestry.

Perhaps Scolland’s witnesses knew something?