In this chapter, Harold has come back from his ineffectual meeting with the Northumbrian rebels and must relay their demands to King Edward and Tostig:

In this chapter, Harold has come back from his ineffectual meeting with the Northumbrian rebels and must relay their demands to King Edward and Tostig:

TOSTIG REMEMBERS

Editha and I stood next to the wall watching as Harold entered the great hall accompanied by a group of men who were very nervous; the newcomers seemed reluctant to hand over their weapons as required by law. Finally they consented but stood in a little clump next to the door. I gasped, recognizing a few of them. They were some of the very thegns who undoubtedly murdered my household. Editha put a hand on my harm, shushing me.

Harold pulled away from them as soon as he could. He looked around for the king, then entered Edward’s presence chamber alone. I could see his face; it was drawn with worry lines. He was pacing the chamber when Editha and I came in behind him. Then he whirled around, expecting the king. He let out a big sigh when he saw me.

“Tostig,” he began. “Sit down.”

I refused. He wasn’t going to stand over me.

“Tostig,” he began again. “They are a rabble. They are ravaging the country around Northampton. And soon they will be moving on to Oxford.”

I looked at him in disbelief. “Then we must raise the fyrd,” I began hesitantly. “We need an army to put them down.”

The door slammed behind us. It was the king.

“What is this about the fyrd? What happened at Northampton?”

Harold kneeled before King Edward. “The rebels took you at your word,” he said. “They sent representatives to put their case to you in person.” He stood and looked over at me. “I could get nowhere with them.”

Edward looked troubled. “They will not accede to my demands? That they cease their ravaging?”

“For a short time. It appears they want to show you how powerful a force they are. I believe they are prepared to overrun East Anglia if you do not accept their terms.”

I stared at Harold, not believing what I was hearing.

“What are you saying?” I couldn’t help myself. “You let them dictate terms to you!” I could barely control my voice. For once, Edward did not stop me.

“Tostig,” Harold tried to cajole me in his most manipulative voice. “That’s why I wanted to prepare you for this. They were unruly, but they were united. They had many grievances. And more than that: I believe they have been plotting this rebellion for some time. Why else would Morcar be on hand to accept the earldom?”

My brother spoke out loud what I dared not think to myself. Before I had time to consider the consequences, he turned back to the king. “The men would present their complaints directly to you, in front of our assembly. I could not say nay.”

Editha had a hold of my arm. “Let them speak,” she whispered in my ear. “We must know what their plans are before we can foil them.”

My sister was always the voice of reason between Harold and me. I allowed her to pull me from the room. I stood aside as the king passed and my sister kept her hand on my arm. Edward made a majestic entry into the witan chamber with Harold; my sister and I followed. The assembly bowed to the king and the rebels came forward as one.

“Sire,” the spokesman said. “We come before you freemen born and bred. It is not in our blood to bow before the pride of any earl. We learned before our fathers to take no third choice between freedom or death.” He looked up at Edward, avoiding my eye.

“If you want to keep Northumbria in your allegiance, we insist you confirm the banishment of Tostig from our earldom and from the kingdom. If you persist on forcing Tostig on your unwilling subjects, we will deal with you as an enemy!”

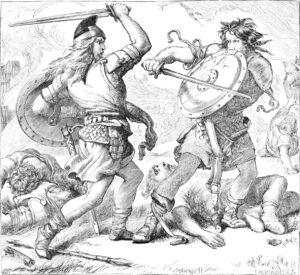

At that, I lunged at his shaggy face, wanting to crush his throat in my bare hands. Harold grabbed me and forced my arms behind my back.

The bastard wasn’t finished. He bravely faced me while Harold held me firm. “We have already elected Morcar as our earl,” he shouted over the commotion. “You must confirm our election! If you yield to our demands, you will see what loyal subjects your Northumbrians can be, when ruled by a candidate of our own choosing.”

Staggered, I went limp in Harold’s arms. He let me go gently. I don’t think I believed what could happen—what was happening—until this moment. I stepped behind the king and used the back of his throne for support.

But the worst was yet to come. The hall was in an uproar, and Edward insisted that the Northumbrian deputation be removed from the room while their demands were discussed. At first, I had to listen to the same old accusations again, but Edward finally put a stop to that.

“Silence,” he shouted. “We are not here to determine why the Northumbrians revolted, but how to stop their depredations.”

That helped quiet the room down. “There is no justification for their illegal actions,” the king continued. “They have pillaged and killed my lawful subjects. They have risen up in rebellion against Tostig’s lawful rule. They must be punished.”

Finally! I stood straighter, more confident now that the king was in control.

Harold cleared his throat. “Sire,” he said, beginning slowly. “Are you speaking of civil war?”

Edward turned to my brother impatiently. “Call it what you will,” he said disdainfully. “These people must be chastised. They are in rebellion against their king!”

The room fell silent. Edward looked around at the witan. Where was his support?

I could feel myself losing patience, but I bit my tongue.

“Sire,” my brother ventured again. “What would you accomplish but more bloodshed? If you compelled the Northumbrians to take back the rule of Tostig, how would we enforce it?”

“Enforce it?” I exclaimed, no longer able to control myself. “What are you saying, brother?” I seized him by the arms and faced him, eye to eye. “We will enforce it with our soldiers!”

“We would have to lay waste to your whole earldom! Is that what you want?”

“If that’s what it takes, then yes!”

“Tostig, aren’t you listening? They won’t take you back!”

This couldn’t be my brother speaking! “I beggared myself for you,” I spat. “For your endless Welsh campaign, so you could come home with all the glory! Is this how you thank me?”

My brother ignored my taunt. Leaning to one side, he tried to look around me at the king. “Think of what they are threatening, Sire. They are threatening to ravage Northamptonshire as we argue. Think of what they are doing to our country. I was there. I heard how uncompromising they were. It might be better to consider their demands.”

I couldn’t believe my ears! I tightened my grip on his arms.

“You can’t be saying this!” I shouted in his face. “You must have instigated this rebellion! You! Who insisted I raise all the taxes! You knew what would happen! You must be in league with Edwin and Morcar! How could you turn on your own brother!”

The uproar continued, but Harold and I were locked in a private struggle. I stared him down; he was the first to look away.

“I swear!” he roared over the noise. “I swear to you that I knew nothing about this rebellion.”

“We already know what your oath is worth,” I growled. I doubt anyone heard me except Harold and King Edward.

But Harold was busy pointing up in the air and calling for attention. “I am willing to call oath-helpers to prove my innocence. I have witnesses! I swear I am innocent of this accusation!”

“All right, all right,” Edward consented. “That will not be necessary. Now, sit down.”

I didn’t agree with the king. I didn’t move. “My faithful brother.” I spat the words. “Support me in this, else you will lose my loyalty forever.”

Harold blanched. “Tostig,” he pleaded. “Give me time.”

“Sit, Earl Tostig,” the king remonstrated. “You must control your temper.”

I took a deep breath and backed away. It was then that I noticed the silence in the room. Frustrated, I sat down. My sister came up behind me and put a hand on my shoulder. That helped calm me a bit. For a moment.

One of Harold’s under-chieftains stood up. “Sire, it would be very difficult to raise an army so late in the year. How would we provision ourselves?”

“We cannot campaign in the winter,” another shouted.

My brother’s minions all murmured their agreement. Another stood up. “What good would it do for England if Wessex was to make war on Northumbria?” He turned around, nodding his head as others shouted that he was right. Someone else called out, “Why should we support a cast-off earl?”

I stood up at that, but Edward stood too, pointing in my direction.

“I do not call out the fyrd to support a cast-off earl. I call out the fyrd to support my Royal authority!”

It made sense, though I was a little dismayed to be so discounted.

“Those traitors need to be punished!” Edward’s voice was starting to sound like a whine again. I hated when he lost control. I took a step down and approached the assembly, trying my best to sound reasonable.

“King Edward speaks true,” I proclaimed in my most authoritative voice. “All the injured and dead are our countrymen.”

People started shouting at me, brandishing their fists. I bellowed back, to no avail. No one would listen to me.

“I command you to call out the whole force of England to my Royal Standard!” the king ordered, screaming over my head. Nobody heard. Nobody answered.

My arrogant brother just stood there, arms crossed, and waited for the noise to die down. In disgust, I went back to my seat.

Edward collapsed into his throne, his energy spent. After another few minutes, Harold moved to where I had been standing.

“The king requests that we call the fyrd,” he said to a restless but quieter crowd. “But we all would abstain from a civil war.” He turned and looked at me and I narrowed my eyes, glaring at him. “Our father would not do it fourteen years ago. It’s no different now. Our enemies across the sea would attack us at the first opportunity.”

Another stood up. “Even if we forced them to take Tostig back, who is to stop them from rebelling again?” Harold watched while the shouting started all over again.

My brother finally turned to King Edward. “Some of the rebels have crossed into my brother Gyrth’s earldom. They are headed for Oxford. I propose we call a witenagemot of the whole realm, and stop the renegades there before they progress any farther south. Then we can negotiate further.”

The king had sunk further into his throne. My advocate. My supporter. Edward nodded, looked away and waved his hand, granting Harold the power to call his assembly. I knew the signs. The meeting was finished. So was I.

As the crowd made their way out of the assembly hall, I went up to Harold. He didn’t want to look at me but he couldn’t help himself. He was drawn to me like a moth to a flame; my ire was such that he couldn’t avoid me, though he knew my righteous anger was going to burn deep. We’ve opposed each other before, but not like this.

“Brother,” I said to him. I couldn’t keep the threat from my voice. “I hope you bestow some sense on my Northumbrian traitors. Because if you do not, I swear to God Almighty that you will regret it for the rest of your life.”

Not trusting myself further, I turned on my heel and headed for the king’s personal door. Turning, I looked back and saw my sister, standing and glaring at Harold. At least she was on my side.

Universal Link: buff.ly/3w8xEZi