Harold’s ill-fated trip to Normandy has sparked much debate among historians. Why did he go? How much damage did it cause? One thing is certain: Harold and William were far from strangers by the time they met on the battlefield of Hastings.

It is thought by some that Harold was on a fishing trip in the English Channel when a sudden rain squall blew his boat all the way to Ponthieu in 1064. Count Guy, as was his right, took Harold hostage and was apparently quite put out when Duke William showed up shortly thereafter and demanded that he give Harold up. A proverbial case of From the Frying Pan Into The Fire! Once Harold was the unwilling guest of Duke William, he knew he wasn’t going to get out of there without some painful concessions.

Norman chroniclers favor the story that King Edward sent Earl Harold to Normandy to confirm his choice of William as heir to the English throne. The obvious argument against this legend is that King Edward had no legal right to appoint his successor. Although the king’s last wishes were always considered, the final decision was with the Witan, the king’s council. I don’t think this alleged promise was common knowledge in England—if it happened at all. It is far from certain that William visited England in 1052 (while Godwine was in exile). If this didn’t happen in 1052 and William’s plans were not common knowledge, there is a possibility that Harold didn’t know about William’s aspirations to the crown until he visited the ducal court.

There are other explanations about Harold’s intentions. It has been theorized that he was sounding the opposition, so to speak, for his own bid to the throne. But in 1064 King Edward was in good health and Edgar Aetheling, the true heir, was being raised at the royal court. The motivation that makes the most sense to me is the possibility that he went to Normandy in an attempt to secure the release of his brother Wulfnoth and his nephew Hakon, held hostage since around 1052. Alas, even this attempt failed (only Hakon was released) and ironically Wulfnoth’s isolation probably protected him from the same fate as his brothers.

Harold’s stay at William’s court was protracted and cordial – at least on the surface. During this time, Duke William led a punitive expedition against Conan of Brittany, taking Harold with him and fighting side-by-side with the famous Saxon Earl. The Bayeux Tapestry shows a scene where Harold wades into quicksand to save two Norman soldiers from certain death. After the siege of Dinan, William gave Harold arms and weapons and knighted him for his valor.

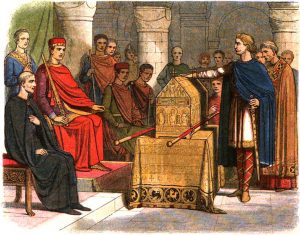

Nonetheless, once Harold became William’s man—so to speak—it was time for him to return home. But one final concession had to happen first: the great oath. In front of all the Norman barons, Harold was obliged to swear an oath to support William’s claim to the English throne (against his own interests, even then), swear to secure the castle of Dover for William (not likely!), to marry one of William’s daughters. Knowing this was his only way out, Harold duly swore the oath knowing that under duress, many an oath was often considered invalid. However, William was too smart to be outwitted; just to make it stick, he secretly laid the bones of Normandy’s saints beneath a tablecloth on which stood the bible. Once the pledge was sworn, the tablecloth was whisked off and Harold was aghast that he had just sworn a false oath on holy relics.

The consequences of Harold’s oathbreaking were grim indeed; William used this event to help win the pope’s approbation for his conquest of England. When the Duke unfurled his banner at the Battle of Hastings, he placed the Pope’s banner alongside for all to see. The Normans went so far as to declare that God had turned against Harold’s kingdom and shown his favor to the invaders. I would think that Harold still felt a sting of guilt, regardless. Even his brother Gyrth is said to have offered to lead the army at Hastings since he wasn’t bound by any oath, but Harold scornfully rejected the idea.

One thing is for sure; as a consequence of this ill-fated voyage, both Harold and William knew how their future opponent would conduct himself on the battlefield. Harold would have returned to England a much wiser man and better prepared for the future; too bad he couldn’t change the course of his destiny.

Johnny H says:

Hi Mercedes, a great blog!

I have always believed that Harold’s mysterious visit to Northern Europe didn’t originally plan a trip to duke William’s Normandy!

Perhaps he was trying to free hostages (younger brother, Wulfnoth and nephew Hakon?) taken from England in 1052 (by an ousted and fleeing Archbishop Robert Champart, avoiding the returning Godwineson family?) to give to duke William?

Maybe he was trying to broker some powerful Political alliance or marriage with a Continental nobleman to one of his sisters (the ‘Aelgifu’ seen in the Bayeux Tapestry?)?

Perhaps William was trying to make Harold confirm the oath which his father had apparently made in 1052 to Edward? That being, to offer up Dover and equip and man it at his own expense?

Other sources say that Harold was trying either to simply go on a fishing trip that got caught in a storm (in the Bayeux Tapestry), or was actually supporting William regarding the succession promise that Edward had supposedly given William in his brief visit to his distant royal kinsman in 1051 (after the Godwinson clan had been exiled)?

Whatever the true cause of his visit, from which he returned with Hakon to an apparently frowning King Edward (Tapestry), I think the oath he apparently gave to William invalid, as you also said.

I say this because it was made outside England and her laws and possibly meant totally different things to English and Norman?

Even the Normans (Poitiers) state that it was made “over hidden relics” which strongly suggests deceit, and no-one seems to agree where the oath was held?

Harold would have been mindful of William’s reputation for cunning, coercion and brutality (Edward’s own nephew, Walter of Mantes, was poisoned in a Norman gaol at this time – hardly conducive to becoming enamoured to the king?) and at Alencon and Mortemer, and may well have gone along with the ‘oath’ simply to ensure the safety of his entourage, hostages and himself?

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Hi Johnny,

Thanks for your posts! It’s a pity we have so little to go on and so many possibilities. In the end, I agree that Harold would probably have agreed to anything just to get away, with the assumption that very few oaths made under coercion stand up in the end. Too bad for Harold the Pope didn’t need much convincing to throw his support behind the Norman banner.

I don’t think I ever heard of Godwine’s oath to offer up and equip Dover at his expense? Since Dover was already part of his earldom, would this have been an exception… to Offer it up to the Normans? Could you point me in the direction of this episode? I would be grateful for further study.

Johnny H says:

Hi Mercedes,

I agree, the sources seem so vague or contradictory! I think that Harold deliberately didn’t send an embassy to the Pope – maybe he still remembered the near disastrous embassy of Tostig and Ealdred’s in 1061?

As for the suggested theory regarding Godwin and Dover (an oath to offer up Dover to Norman usage?) it was Paul Hill in “The Road to Hastings” (bottom p.134) when he says:-

“But the most important thing about Harold’s time with William was that he certainly seems to have sworn an oath. The strongest likelihood is that the oath…was a renewal of the one which Godwin had sworn in 1051 (see pages 102-103)”

Intriguing? It was tied up with both Eustace’s and William’s mysterious visits to England in 1051 just after the Godwinson’s had been exiled and fled.

Eustace and William were never true friends, and the former seems always to have had a fixation with this vital coastal town castle- causing havoc in both 1051 and 1067?

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Hi Johnny… greetings from New Jersey! My question is, how (or why) did Godwine swear an oath in 1051 while in exile? Or was this before his exile while trying to curry favor??? I have read that Edward might have promised England to William in 1051 (while Godwine was in exile), although he must certainly have known that his promise meant nothing without the approval of the Witan.

I never ran across Paul Hill before, but I just found a copy of his book on Amazon. I’ll give it a try, thank you very much.

Johnny H says:

Hi

If my memory serves, Godwin was obliged to pay homage to Edward during the build-up to the crisis of 1051, whereby Edward gathered huge forces (earls Siward of Northumbria and Leofric of Mercia) against the Godwinson clan in that infamous stand-off before they were exiled.

It’s been a while since I read it, but perhaps Godwin may have been too strong to be forced to swear anything to Edward after his triumphant return to power in 1052?

Mercedes Rochelle says:

I do remember reading that Godwine paid some sort of homage to Edward (short of putting himself at the King’s mercy) before his exile, but on his return I imagine he was holding all the cards, so to speak.

I just received a copy of “The Road to Hastings”, thank you very much. Maybe I’ll learn something new! I admit that Edward A. Freeman is my “go-to” for much of my research; I found my precious set in England two decades ago. Alas, he is SO thorough it’s easy to get bogged down!

Johnny H says:

I agree, in 1052 it was definately Godwin who was in charge of Edward! Yet he didn’t rub it in or attempt a coup despite his triumphant return to power?

Harold and Tostig also seem to have been very loyal and friendly with the king, in spite of his thoughts about their father!

As for sources, I tend to absorb a few of the more modern scholar’s books (ie. Peter Rex, H.J.Higham, Michael Wood) for their tantalising theories and dissections of the sparse contemporary sources.

Paul Smyth says:

Great blog and fantastic post. Nice to see someone reminding us that Edward had no right to appoint either Harold or William heir. My question is this, regardless of why Godwine ended up at William’s court, what is the evidence that any oath was sworn? Do we have written English accounts on Harold’s return where he declared the oath? How do we know that, like many other things, this isn’t just another Norman pack of lies meant to justify William’s actions, particularly to the Pope? More and more I find it hard to believe a single word written by a Norman.

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Great question, Paul. I went back to Edward A. Freeman’s exhaustive History of the Norman Conquest of England, and in volume 3 our venerable scholar approaches this question from every possible angle (it helps to read Latin). He states that there is no consensus as to the exact place of the famous oath, or even the exact date (some place it before the Breton campaign), nor the exact terms. However, even Freeman has to admit that SOMETHING bad happened, because not a single English source denies it took place. If Freeman could have dug up a refutation, he most certainly would have jumped on it! I guess it makes sense that all the sources are Norman, since the event took place over there.

Joe Robinson says:

Just an observational aside:I believe it’s also worth remembering that Harold might have considered he was in mortal danger, stranded in Normandy with a powerful, ruthless Demi-King such as The Bastard; his younger brother Wulfnoth and nephew Hakon had been held captive for a decade; William had no doubt paid handsomely for the release of such a pawn for his grand game. William wanted payback. Harold could be traded for promises; and he would have known that. Promise much, deliver little.

Joe Robinson says:

Please see my reply to Mercedes.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

Ok, Keats-Rohan’s article in English is copyright 2012, available at https://www.academia.edu/6013651/Breton_Campaign1064.

A French language version was published in Mémoires de la Société d’Histoire et d’Archéologie de Bretagne xci (2013), 203-44.

Quoting:

” Three very important papers on the Bayeux Tapestry, or rather, Embroidery, were published in 2004 by Pierre Bouet, François Neveux and Barbara English. All three argued convincingly that the tapestry is an original source of the highest importance, because (the fantastical Carmen de Hastingae Proelio apart) it is the earliest source to give full account of the events leading up to the conquest of England in 1066. It covers a period stretching from early 1064 until the coronation of William of Normandy at Christmas 1066 – though this last scene has long since been missing from the end of the tapestry.”

Comment: Was that just neglect or did someone tear that piece off deliberately? If so, who and why?

Re Harold Godwinson:

“The chief reason for dating the completion of the [Bayeux] tapestry before the end of 1069 is its portrayal of King Harold. No derogatory adjective is ever applied to Harold. Indeed, he is portrayed as a hero by his rescue of Normans trapped by the treacherous quicksands in the bay of Mont-St-Michel.”

“At first, William was anxious to govern his new kingdom according to English norms, and was content to accord his fallen rival the title of king, rex.”

Now, that’s interesting.

“After the first of a series of revolts by the English broke out in May 1068, the situation quickly changed. Harold was condemned as a blasphemous usurper, who had betrayed both his predecessor Edward the Confessor and his successor William of Normandy. The only title he was thenceforth accorded was

comes, ‘earl’.”

Prescient shades of 1984’s Ministry of Truth!

“Other key signs of an early date for the Tapestry

are its reference to a woman with an English name and a cleric at Rouen, followed by an extended campaign in Brittany conducted by William in the company of Harold. A second

important strand of Bouet’s argument, based in large part on the Latin in the Tapestry’s tituli, as well as some of the iconography, is that the whole work represents a collaboration between the Normans and the English. ”

“I am in complete agreement with these views; but I think we can go very much further.”

(To be continued.)

Geoffrey Tobin says:

The authority of kings and bishops is a strong emphasis of the Tapestry, as is its English and Norman collaborative nature and its current of pro-Englishness. It wasn’t Bishop Odo who was its patron; instead, he, who stood pivotally at the intersection of church and state power, was its intended recipient. So who was its patron and what was the motive?

The breakthrough statement of Keats-Rohan’s article is the statement that the patron of the Tapestry is identified beside his lord and king in the centre of the work, Archbishop Stigand.

Sigand’s motive was to retain his position of authority as Archbishop of Canterbury, which he would some years later lose due to Lanfranc’s legal challenge to both Harold’s and Stigand’s legitimacy, a case Lanfranc prepared from 1075 to 1077.

Keats-Rohan says that with this realisation, much now falls into place. Everyone was trying to make sense of what happened and to make the best of their situation.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (written by English monks) explained the English defeat as caused by provoking divine displeasure.

Harold’s sister Edith, widow of Edward the Confessor, commissioned a life of her husband portraying him as saintly and as leaving the government of England to others including her. She had to compensate for her share of reponsibility: failing to produce an heir (causing the much-disputed succession), and her provoking Tostig which led him to rebel (Battle of Stamford Bridge).

Comment: what were the Bretons’ contemporary views of events, and where might we find them?

The Norman view evolved, from William of Jumiege’s bland and sparse account written before 1070 and the vilification of Harold, to William of Poitiers’s detailed description [with its fuming bigotry] written during the vilification era.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

Here is Keats-Rohan in full literary flight.

“It is not enough to look at the tapestry and to say that because there is no other evidence, the tapestry must lie in order to glorify William. It is true that the tapestry can appear to say one thing and mean another. No two historians have ever agreed about anything in the tapestry since it was first discussed. It is the inspiration of a master manipulator, well versed in the black arts of power, working together with an artist or artists of genius.”

Geoffrey Tobin says:

Francis Bret Harte (25 August 1836 – 5 May 1902), American author and poet, wrote “The Tales of the Argonauts” in 1875. He’s thus very likely the inspiration for George R. Stewart’s hero of that name.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

On the funny side, “They Call the Wind Maria” has lyrics by *Alan* (J. Lerner) and was first sung on Broadway by *Rufus* (Smith).

Proves that connections with Alan Rufus really are everywhere – if one searches Harte enough. 🙂

Peggy says:

Your blog is so interesting! I would like to postulate another scenario: Edward was not as saintly as we have been led to believe – his statement to Godwin to “restore is dead brother” to put an end to their conflict and his treatment of his mother show a vindictive man. He had, for all intents and purposes, lost his power to the Godwins and the English nobility supported Harold, not him. So, what if he DID offer the crown to William? He had to know that William would have taken it as an unbreakable promise. What if he DID send Harold to Normandy? Could it be that his final revenge was to offer the crown to Harold on his deathbed, knowing what William’s response would be? He wold have gotten his revenge on, not only the Godwins (whom he could be sure William would destroy), but also the English nobility who had not supported him. Just my thoughts about palace intrigue…

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Hi Peggy. A perfectly reasonable approach! One would hope that the King of England was not so vindictive, but it is certainly a possible scenario, especially in 1051. Allegedly his bile against Godwine did not extend to his sons (Tostig was a favorite), but maybe the damage was done. Hmm.