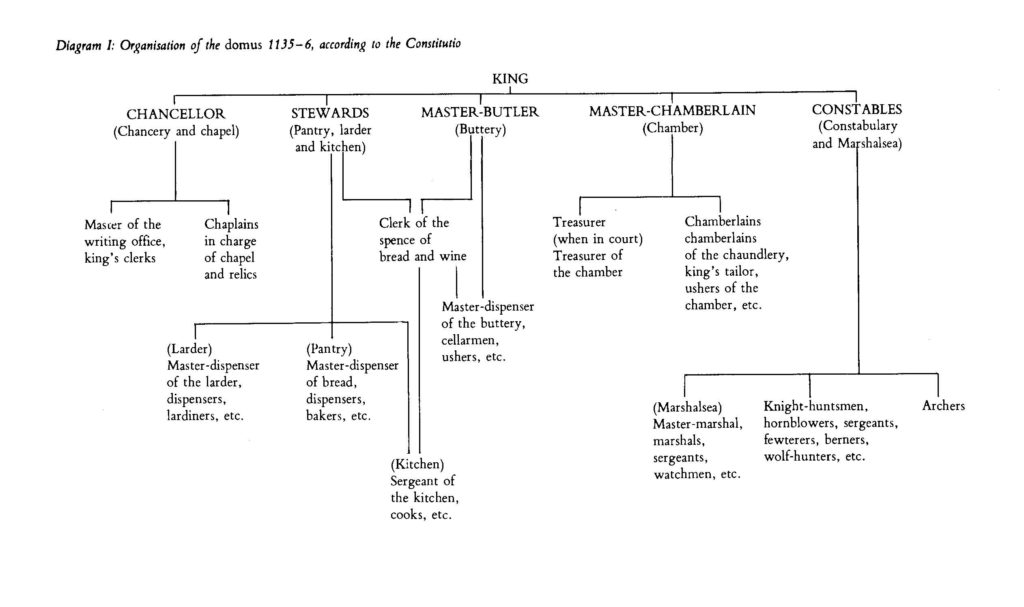

As my title suggests, the king’s wardrobe was actually broken into four parts. Each part had its own officer, separate function, and different location. And surprisingly, their names aren’t always intuitive.

The WARDROBE, was the most important and expensive of the four. It was responsible for the king and his household’s expenses, such as food and drink, coal, wood, candles, etc. as well as oats and litter for the horses and daily wages. Incidental expenses for the household such as medicine, ink-horns and parchments were included, as well as gifts, robes, hunting expenses, and the cost of entertaining foreign ambassadors. For the last several years of King Edward III’s reign and the first half of Richard II’s reign, Wardrobe expenses hovered around £18,000. But after Queen Anne’s death in 1395, when Richard was accused of excessive extravagance and especially when he employed his 300 Cheshire archers as bodyguards, his expenditure swelled to over £37,000. Ironically, even though this was a bone of contention, King Henry IV continued this huge spending spree, allegedly because he preferred to maintain a large and extravagant domestic establishment. Eventually he had to bow to the complaints of Parliament, and managed to bring his annual expenses down to about £19,000.

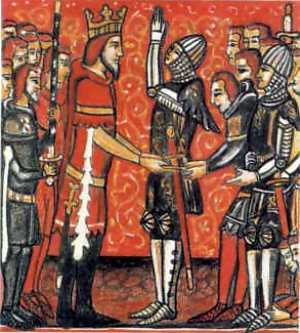

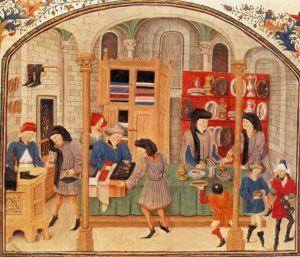

The GREAT WARDROBE was responsible for cloth, furs, and linen. These were for robes (sometimes part of an annuity, as well as robes for tournaments, marriages, funerals, anniversaries, chapel vestments, trappings for royal horses), wall hangings, coverings—even garters. Just to give an example of how costly certain events could prove, “for Princess Joan’s funeral (mother of the king) in 1385, the keeper had to provide special mourning robes for four earls, ten bannerets, fifty-four knights, forty-eight clerks, 161 esquires and sergeants, 157 valets, eighteen minstrels, a further 320 lesser servants of the king” (see “The Royal Household and the King’s Affinity” by Charles Given-Wilson). No sewing machines; they must have needed a whole army of seamstresses.

The Great Wardrobe was also divided into four sub-departments, headed by a tailor, armorer, pavilioner, and embroiderer. It was housed next to Baynard’s Castle between St. Paul’s and the Thames; this house was purchased by Edward III in 1360 and remained in use until the great fire of 1666. As in the Wardrobe expenses, there was a huge escalation of costs from the early part of Richard’s reign (averaging about £3,000-£3,500 a year) to £8,000 at the end of his reign. This is attributed to his great love of finery.

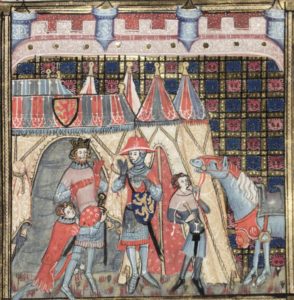

The PRIVY WARDROBE was essentially dedicated to arms and armor and was located in the Tower of London. Although the stock of weaponry was impressive (among the 1396 inventory it contained 796 basinets, 2328 bows, 1392 coats of mail, 11,300 quarrels, 14,280 arrows), this was the least expensive of the four household departments. This is because the sheriffs were expected to provide most of the weaponry, deducting the costs from their annual payments to the exchequer. When members of the king’s household were sent out on military duties, they were usually equipped from the Privy Wardrobe.

The CHAMBER, as you would expect, was the king’s personal wealth. This included his jewels and plate, which were sometimes used as pledges for loans. How was the Chamber money accrued? Income from the king’s personal estates, fines, wardships, ransoms (remember the French King John?), licenses, traitors’ chattels, dowries (800,000 francs in 1396 for little Princess Isabella) among other sources. Money was passed back and forth between the Chamber and the exchequer; not only was the Chamber given annual installments, but there were times the king would deposit large sums in the exchequer. According to Given-Wilson, “between 1368 and 1377, Edward in fact transferred a total of more than £160,000 of his personal wealth, from the chamber, the Tower hoard, and the ransom installments which continued to accrue, into the exchequer, the vast majority of which was spent on military needs”. Since the Chamber money was the king’s business and nobody else’s, there are no official accounts for historians. Nonetheless, Edward must have collected quite a hoard, for in 1365-66 he erected the Jewel Tower (pictured) in the Palace of Westminster which was surrounded by a moat.

As you may suspect, this post concerns the reigns of Edward III, Richard II and Henry IV as described by Chris Given-Wilson. If you are interested in the early development of the Wardrobe, I heartily recommend T.F. Tout who has written four volumes on the subject entitled “Chapters in the Administrative History of Mediaeval England” which have recently been reprinted. Both of these historians have contributed greatly to our knowledge of the period.