The manorial courts were one step up in law enforcement from the tithings that we looked at last week. Each manor had a court and the court governed the lives of everyone who lived on the manor, even determining when they could plant and when they could harvest. It fined them if they allowed their animals to stray onto the lord’s demesne, and it was where they took their claims against one another to be judged.

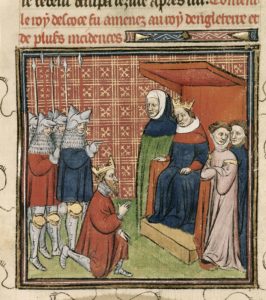

The manor was made up of the lord’s demesne as well as the land that he leased to tenants. The demesne was the farm that the lord kept for his own benefit. The people who worked the manor’s land were both freemen and serfs (cottagers, smallholders or villeins). The manorial court dealt with the serfs’ issues, while the freemen were able to go to other courts, which we’ll come to later. It was also able to create new bylaws for the manor.

Some lords had more than one manor and could not look after all of them closely, or they were away at war or absent for some other reason. The manorial court was one of the ways in which the manor could be managed whether the lord was there or not. He had a steward, who looked after his interests in his absence, but it was the village officials (reeve, hayward and beadle amongst others) who made sure that things happened as they should.

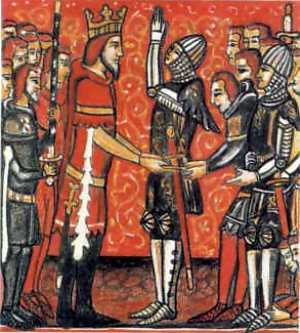

The manorial court decided the land boundaries and the days on which animals could graze in the fields. The steward presided over the court, but the village elected the officials from among themselves. The steward could not tell the court what to do and the court could appeal to the lord if necessary. Usually the business transacted by the court had no direct reference to the lord’s own affairs since it dealt with village problems such as loans not being repaid; men not turning out to work on the lord’s demesne; theft; the erection of a fence in the wrong place; or one villager injuring another.

The court was run by the rich villeins who provided the jurors and officials. The court was supposed to meet every three weeks, but some met less often. All the serfs in the village had to attend. Those who did not were fined. The court was often held in the nave of the church, the part that ‘belonged’ to the village. There were not many places in the village large enough to hold the court and many were simply held in the open air, often in the churchyard. Some manorial courts met in the hall of the manor house itself.

The jurors pronounced judgement on their fellow villagers (and occasionally on the lord) and this was sometimes put to the rest of the village as well for their assent. When making a judgement they had to take into account what they knew of the law, the customs of the manor and the manor’s bylaws. All the jurors and everyone else in the court knew both parties in every case that was brought before them, which was supposed to make it easier to come to a correct judgement. The system of justice was mostly based on the way in which society worked. People lived in small communities where everyone knew everyone else’s business and character. If you, as a villein, were asked whether your neighbour, Peter, had stolen from another neighbour, John, you would know the characters of both men and could assess whether John was making a false claim against Peter or whether Peter was a known thief. You did not have to have seen the (alleged) crime take place in order to be able to work out what had happened, nor did you need any evidence.

Villagers had to pay a fee to the lord get their case heard. The lord of the manor benefited from any fines issued by the court and the court was often the source of a large part of the lord’s income. The manorial court also required payments to the lord on all kinds of occasions – death, inheritance and marriage all had their appropriate fee. When these things happened part of the lord’s land was transferred from one person to another and the fee was to obtain the lord’s permission for that transfer. The court could generate a lot of income for the lord, and fines and fees tended to increase after the Black Death when there were fewer tenants to pay rents. The steward’s clerk recorded the cases and any fines or fees. As well as fines which went into the lord’s coffers, the court could also award damages to be paid by the guilty party in a case to the injured party.

One of the commonest cases to come before a manorial court was the accusation that someone was selling ale before it had been tasted by the ale taster. Ale was brewed at home and sold to the neighbours, who came to the brewer’s house to drink it. The ale taster’s rôle was to ensure that a consistent quality and price were maintained.

It is thanks to the surviving manor court rolls that so much is known about everyday life in the Middle Ages in England. What they show, however, is the things that went wrong and not the things that happened exactly as everybody thought they should.

Sources:

England in the Reign of Edward III – Scott L. Waugh

Life in a Medieval Village – Frances and Joseph Gies

Making a Living in the Middle Ages – Christopher Dyer

The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England – Ian Mortimer

APRIL MUNDAY is the author of the Soldiers of Fortune and Regency Spies series of novels, as well as standalone novels set in the fourteenth century.

Available now:

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/Heirs-Tale-Soldiers-Fortune-Book-ebook/dp/B075KQ3HX4/

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Heirs-Tale-Soldiers-Fortune-Book-ebook/dp/B075KQ3HX4/

Website: https://aprilmunday.wordpress.com/

Twitter: http://www.Twitter.com/AprilMunday