Bastard Feudalism is a term I kept bumping into during my recent research into the fourteenth century. I finally had to stop and investigate. Just what is it, and how does it differ from feudalism as I’ve always known it? It turns out that this was originally used in the Victorian era; the term “bastard feudalism” was derogatory—implying a corruption of feudalism, debased and degenerate. But as time went on, historians came to define it more as a term implying a superficial imitation of the original social order, though different in its essence.

Just to review, Feudalism was brought to England with the Norman Conquest. Like everything else, I’m sure the Anglo-Saxons had a hard time making the adjustment, but the concept of Feudalism was harshly efficient. The king owned everything, and the system is based on land tenure (coming from the French word tenir—to keep), the relationship between the tenant and the lord. The king chose to lease out portions of his kingdom to loyal barons; in return they offered military service, paid rent, and served on the royal council. They had complete control of their Manor, as it was often called; they meted out local justice, minted coins, and collected taxes. The Baron, in turn, divided up a portion of his Manor among his knights, who agreed to offer protection and military service when called upon. The knights lorded it over their villeins, or serfs, who owed them service and provisions. This went on pretty much until the Black Death disrupted the abundance of available workers on the Manor and created a situation where cash was becoming more important than labor.

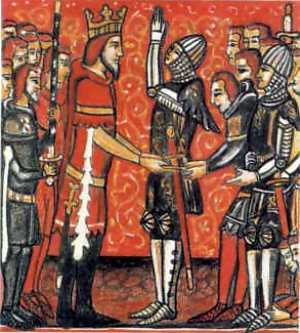

The term “bastard feudalism” was coined in 1885 by historian Charles Plummer, when he needed a term to define the changing relationship between lord and vassal in the two centuries after the death of Edward I. Slowly but surely, the tenurial bond gave way to a social tie depending on a personal contract. Mutual benefit became the keyword. Although military service was important, the relationship between master and retainer became more of a matter of reciprocal services; the lord offered patronage and contracted to protect and defend his vassal in court—maintenance—as well as in combat. He would pay his retainer an annuity, or a fee for specific services rendered; he would often feed and house his annuitant. The retainer was usually expected to contract for life, but by no means was this universal and the indenture was not expected to be binding on the heirs of either party. By the end of the fourteenth century, according to K.B. McFarlane (England in the Fifteenth Century, Collected Essays), there is “evidence to suggest that under the Lancastrians less permanent forms of contract were coming into favor.” Stipends were paid to household officers and servants, civil servants, surgeons, chaplains, falconers, cooks, and even minstrels.

When it came to the lesser gentry, ties between them and the great lords often followed their feudal connections. According to Simon Walker (The Lancastrian Affinity 1351-1399), “bastard feudal loyalties were often the legitimate heirs of fully feudal ties. Precisely how often is rather more difficult to say. By the late fourteenth century, territorial proximity was usually more important than tenurial dependence in creating links between the magnates and the country gentry… it was the expectation of such additional fiscal benefits, not the mere possession of land, that bound the duke’s tenants more closely to his service.” At the same time, if a man owned several manors scattered throughout the country, McFarlane tells us “by this date tenurial relations were so interwoven that a man with several manors could scarcely avoid holding them of nearly as many lords.” If there was a potential conflict, one can only assume the vassal went with the lord who had the most to offer.

By Lancaster’s time, it was not at all unusual for a retainer to collect fees from more than one master for specific duties; think of today’s lawyers, accountants, or estate managers. This could very well be of benefit to both parties; the retainer could make money from several sources, and the magnate could stay informed. Simon Walker tells us, when Gaunt paid annuities to some of King Richard’s chamber-knights: “the king’s household was a center of gossip and accusations against the duke and it was by having his own men there that Gaunt was best able to thwart the efforts of his enemies.” It sounds a lot like spying to me, but if everyone agreed on the arrangement, I suppose it was routine.

From what I can gather, the whole concept of “bastard feudalism” is fluid; not every historian uses it, nor do we find an easy definition. It does make sense that cash was a strong incentive. It was a precious commodity and major magnates like John of Gaunt—not to mention the king—still represented a powerful influence.

Leofranc Holford-Strevens says:

But is it agreed, despite Brown and Reynold, that feudalism ever existed?

Mercedes Rochelle says:

It could be a matter of interpretation. History usually is.