Bibliotheque Municipale, Rouen

The more I research, the better I understand that what goes on behind the scenes is just as important as the high-profile episodes defining a king’s reign. So naturally, I was thrilled to discover “The Royal Household and the King’s Affinity: Service, Politics and Finance in England 1360-1413” by Chris Given-Wilson; this book brought me as close to the 14th century court as a layperson could hope to get. I’m highlighting the book’s major components, for there is a lot to learn here and I’d like to emphasize the parts that I found critical to my understanding. The author tells us that the king’s permanent staff numbered between 400-700 members, though when you add in the servants of the senior household officers, the foreign dignitaries with their staff, guests and hangers-on, the number of people at court could easily have surpassed 1000. That’s a lot of mouths to feed!

Bear in mind that in this period the king did not have a permanent address. King Richard tended to use residences within thirty miles of London, and he would typically stay in one place for maybe two weeks up to two months. Favored palaces were Windsor, Ethan and Sheen. Other royal houses included Havering, King’s Langley, Clarendon, Easthamstead, Woodstock, Henley-on-the-Heath, Kennigton and Berkhamstead. Richard also favored spending a few nights along the way at religious houses—at the monasteries’ expense; perhaps this gave the Exchequer some breathing space! All this moving around meant his household servants considered travel, or “removing”, as a regular part of everyday life. But when you add up all that went with the move—”many hundreds of horses, and a massive store of baggage: crockery and cutlery, hangings, furnishings, clothes and weaponry, wax, wine and storage vessels, parchment and quills, weights, measures, and so on”—the concept is staggering to the modern mind.

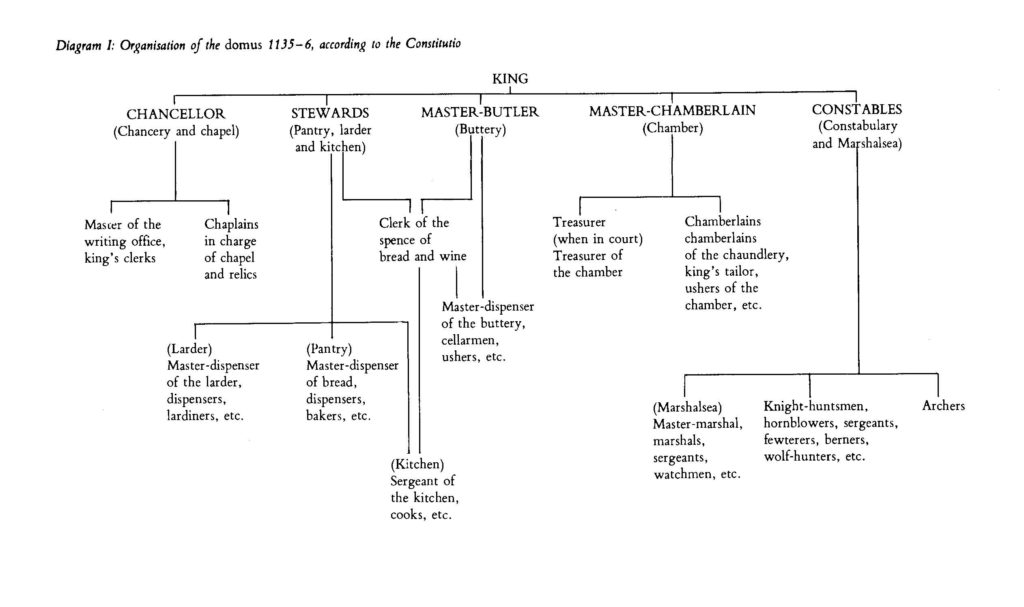

As laid out in the reign of King Stephen, the household was divided up into five main departments as depicted below. There were changes along the way, but I found this chart to be most helpful (before the mid-14th century, the Chancellor had detached itself from the chamber and kept a separate office). In Richard II’s time, the five chief officers of the household were the Steward, the Chamberlain, the Controller, the Keeper of the Wardrobe (or treasurer), and the Cofferer. The Steward was responsible “for the efficient running, discipline, and general organization” of the king’s household. The Chamberlain had overall charge of the chamber; he controlled written and personal access to the king. Both of these officers were the king’s close personal friends, and both were probably of equal status. Naturally they were incredibly powerful, but often contemporaries believed that they abused their position to enrich themselves and gave bad advice to the king; Sir Simon Burley, John Beauchamp of Holt, and William le Scrope paid for their royal influence with their lives. The Controller(s) kept the accounts and was responsible for “supervising purveyance, harbinging, (see below) and eating arrangements in the hall”. The Keeper of the Wardrobe was responsible to the Exchequer for all monies that passed through the household. The Cofferer was the deputy to the Keeper, and held the keys to the money box.

There were changes along the way, but I found this chart to be most helpful (before the mid-14th century, the Chancellor had detached itself from the chamber and kept a separate office). In Richard II’s time, the five chief officers of the household were the Steward, the Chamberlain, the Controller, the Keeper of the Wardrobe (or treasurer), and the Cofferer. The Steward was responsible “for the efficient running, discipline, and general organization” of the king’s household. The Chamberlain had overall charge of the chamber; he controlled written and personal access to the king. Both of these officers were the king’s close personal friends, and both were probably of equal status. Naturally they were incredibly powerful, but often contemporaries believed that they abused their position to enrich themselves and gave bad advice to the king; Sir Simon Burley, John Beauchamp of Holt, and William le Scrope paid for their royal influence with their lives. The Controller(s) kept the accounts and was responsible for “supervising purveyance, harbinging, (see below) and eating arrangements in the hall”. The Keeper of the Wardrobe was responsible to the Exchequer for all monies that passed through the household. The Cofferer was the deputy to the Keeper, and held the keys to the money box.

Each great office had its lesser servants: “they were not just ‘valets’ or ‘garcons’ but ‘valets of the buttery’ or ‘garcons of the sumpterhorses’ and so forth.” Each job was departmentalized, apparently with little cross-over. “By far the largest department of the household was the marshalsea, or avenary (to be distinguished from the Marshalsea Court) which throughout this period employed at least 100 valets and grooms, and sometimes nearer 200.”

Most of the household servants traveled with the king, though a large group went ahead to prepare the way. The 30-40 harbingers‘ job was to requisition lodgings for everyone; the nine purveyors commandeered supplies within the verge (12 mile radius from the king’s actual presence). “Then came the king himself, preceded by his thirty sergeants-at-arms and twenty-four foot-archers marching in solemn procession, surrounded by his knights, esquires and clerks as well as any other friends or guests who happened to be staying at court, and followed by all the remaining servants of the household, driving and pulling the horses and carts which carried the massive baggage-store.” With luck, the itinerary was planned several weeks or months in advance or else the king would have to lower his standard of living.

The purveyors had a particularly difficult job, for their activities were almost always a bone of contention. They rarely paid in cash; instead, they often gave the long-suffering supplier a note to be cashed at the exchequer—when the funds were available, that is. The supplier could wait months to get paid, if he got paid at all. And what are the purveying offices? “The Pantry, or bakehouse, for corn and bread; the Buttery, for wine and beer; the Kitchen, for all food not covered by other offices; the Poultery, for poultry, game-birds, and eggs; the Stables (or avenary, or marshalsea), for hay, oats and litter for the horses; the Saucery, for salt and whatever was needed for sauces; the Hall and Chamber, for coal and wood for heating, and rushes; the Scullery, for crockery, cutlery, storage vessels, and coal and wood for cooking; and the Spicery, for spices, wax, soap, parchment, and quills.”

It’s hard to get our hands around the everyday living arrangements of the king’s servants, but the author likened the king’s residence to the “upstairs and downstairs”. The chamber was the upstairs (quite literally) and the hall was the downstairs (where the servants congregated). The king would descend to the hall and feast communally during banquets and ceremonial occasions, but for the rest of the time he would be secluded in his chamber with his intimates. Edward III had taken to building private apartments for his high-ranking officers and guests. As for the bottom end of the household, “meals were served in the hall in two shifts…it was forbidden to remove food from the hall.” It seems pretty certain that the servants slept anywhere they could: “those who did not sleep in the hall probably distributed themselves around the passageways and vestibules, huddled in winter around the great fireplaces, lying on their straw mats (pallets) which may have been single or double.” Four sergeants-at-arms slept outside the king’s door and a further 26 slept in the hall. “No member of the household staff was to keep a wife or other woman at court”, though prostitutes were regularly ejected.

It’s hard to get our hands around the everyday living arrangements of the king’s servants, but the author likened the king’s residence to the “upstairs and downstairs”. The chamber was the upstairs (quite literally) and the hall was the downstairs (where the servants congregated). The king would descend to the hall and feast communally during banquets and ceremonial occasions, but for the rest of the time he would be secluded in his chamber with his intimates. Edward III had taken to building private apartments for his high-ranking officers and guests. As for the bottom end of the household, “meals were served in the hall in two shifts…it was forbidden to remove food from the hall.” It seems pretty certain that the servants slept anywhere they could: “those who did not sleep in the hall probably distributed themselves around the passageways and vestibules, huddled in winter around the great fireplaces, lying on their straw mats (pallets) which may have been single or double.” Four sergeants-at-arms slept outside the king’s door and a further 26 slept in the hall. “No member of the household staff was to keep a wife or other woman at court”, though prostitutes were regularly ejected.

The king’s affinity embraces his great officers of state, magnates, clerks of the royal chapel, councilors, knights, servants, retainers, and other followers. In the next post I’ll concentrate on the many layers of knights in the king’s affinity and their assorted duties.

April Munday says:

Even if there were many permanent servants at each palace, that’s a large household to transport and feed on the journey.

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Hi April! I love the way the author puts it: “for much of the time, therefore, the royal residences—castles, palaces, or just ‘houses’—were lifeless, almost empty, beautiful but statuesque, until suddenly transformed into a veritable maelstrom of activity by the arrival of the king and his followers.” How prosaic!

Geoffrey Tobin says:

Barons had similar staffing arrangements, though surely on a lesser scale. Domesday Book gives some of the names of senior employees, e.g. of Countess Judith. For Richmond Castle, we have the names of the Steward, Chamberlain, Constable, etc., and there’s a helpful medieval sketch of where the knights were stationed on watch: e.g. one was posted at the main kitchen: I’m sure his meal was piping hot.

The Earl of Chester, Hugh “the wolf” (I think this may refer to his appetite), travelled with a large and expensive company of servants, several of whom were probably needed to carry him around, if the tale of his great corpulence is correct.

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Great story! Do you know where I can find that sketch?