Livery and Maintenance went hand-in-hand with chivalry, and created problems throughout the high middle ages. Once I realized that “retaining” was the verb for “retainer” I started to get the idea. The noble or king had his retainers, who were either in his household (given food and clothing) or part of his social and political network (fee’d retainers, paid an annuity for fealty and service). The retainer looked to the lord for “livery”—or clothing (hoods or “chaperons”, cloth, and more specifically, badges; think of Richard III’s white boar)—and “maintenance”—or maintaining the cause, or dispute, of the client. The lord was their protector; if they misbehaved, the retainers were pretty sure they could get off scot free, so to speak, usually by interfering with justice. Not only were judges and juries intimidated and bribed, but, according to Anthony Tuck (Richard II and the English Nobility) “there was a great trade in pardons in the fourteenth century to produce revenue”. This was applicable only when the accused showed up for trial, which rarely happened, anyway; there was no way to force the offender to cooperate.

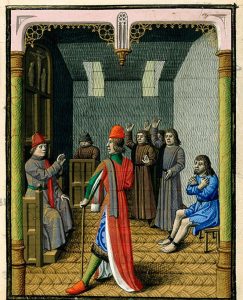

As might be expected, wearing a lord’s livery fostered a lively atmosphere of competition, faction-fighting, and strife. The armed livery retainers were starting to look and act like thugs. I keep thinking about the incredible sword-fight in Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet, where Tybalt and Mercutio led their howling followers in a violent brawl up and down the streets. Innocent bystanders had to fend for themselves. When convenient, anyone could be threatened or abused depending on the inclination of the liveried bully. Law and order was a farce.

All the way back to Edward I’s days, attempts were made to control this disregard for the law. By Richard II’s reign, Parliament tried to order the nobles to cease the practice of liveries, but the Lords insisted they could control their own offenders. Of course, they couldn’t and this caused a constant conflict between the Lords and the Commons which Richard took advantage of, even offering to abolish his own livery if the nobles would do the same. This offer was scorned by the Lords, but it served to create a badly-needed rapprochement between King and the Commons.

In Richard’s reign, retaining took on a special urgency. In return for his loyalty, a retainer expected patronage, advancement, or even acquisition of lands. If the lord couldn’t extend his patronage (for instance, if the king denied him access or offered a better deal), he might very well lose the allegiance of his retainers. This was one of the major grievances of the Lords Appellant, for as young Richard II distributed lands and honors to just about anybody who asked for them, the great magnates saw their influence waning. As Anthony Goodman tells us (The Loyal Conspiracy): “As he (Richard) progressed, he retained… The nervousness it aroused was reflected, too, in the arrest near Cambridge of a servant of the king who had been distributing liveries to the gentry of East Anglia and Essex, on receiving which they swore to do military service when summoned by the king, no matter which lords had retained them.” This became especially true in the 1390s, after the Merciless Parliament when Richard obsessively built a powerful support base. By the end of Richards’s reign, he had retained so many followers that he beat his enemies at their own game; he alarmed London by filling it with an army of Cheshiremen, and in his last two years, their behavior was ungovernable. Alas, for Richard, the more easily acquired, the easier they were lost, and when the final showdown occurred, his standing army evaporated and he faced the usurper alone.

It wasn’t until the Tudors that an end was put to maintenance, and enforceable laws were introduced. By then, chivalry had run its course and the Wars of the Roses had wiped out the overweening might of the aristocracy, leaving a more pliant nobility.