In 1846 William John Thoms, a British writer, penned a letter to The Athenaeum, a British Magazine. In this letter, he talked about “popular antiquities.” But instead of calling it by its common name, he used a new term — folklore.

What did Thoms mean by this new word? Well, let’s break it down. The word folk referred to the rural poor who were for the most part illiterate. Lore means instruction. So folklore means to instruct the poor. But we understand it as verbal storytelling. Forget the wheel — I think storytelling is what sets us apart. We need stories, we always have and we always will.

The Dark Ages is, I think, one of the most fascinating eras in history. However, it does not come without challenges. This was an era where very little was recorded in Britain. There are only a handful of primary written sources. Unfortunately, these sources are not very reliable. They talk of great kings and terrible battles, but something is missing from them. Something important. And that something is authenticity. The Dark Ages is the time of the bards. It is the time of myths and legends. It is a period like no other. If the Dark Ages had a welcoming sign it would say this:

“Welcome to the land of folklore. Welcome to the land of King Arthur.”

Throughout the years there have been many arguments put forward as to who King Arthur was, what he did, and how he died. England, Scotland, Wales, Brittany and France claim Arthur as their own. Even The Roman Empire had a famous military commander who went by the name of Lucius Artorius Castus. There are so many possibilities. There are so many Arthurs. Over time, these different Arthurs became one. The Roman Artorious gave us the knights. The other countries who have claimed Arthur as their own, gave us the legend.

We are told that Arthur and his knights cared, for the most part, about the people they represented. Arthur was a good king, the like of which has never been seen before or after. He was the perfect tool for spreading a type of patriotic propaganda and was used to great effect in the centuries that were to follow. Arthur was someone you would want to fight by your side. However, he also gave ordinary people a sense of belonging and hope. He is, after all, as T.H. White so elegantly put it, The Once and Future King. If we believe in the legend, then we are assured that if Britain’s sovereignty is ever threatened, Arthur and his knights will ride again. A wonderful and heartfelt promise. A beautiful prophecy. However, there is another side to these heroic stories. A darker side. Some stories paint Arthur in an altogether different light. Arthur is no hero. He is no friend of the Church. He is no friend to anyone apart from himself. He is arrogant and cruel. Likewise, history tells us that the Roman military commander, Lucius Artorius Castus, chose Rome over his Sarmatian Knights. He betrayed them and watched as Rome slaughtered them all. It is not quite the picture one has in mind when we think of Arthur, is it? It is an interesting paradox and one I find incredibly fascinating.

But putting that aside, Arthur, to many people is a hero. Someone to inspire to. This was certainly true for Edward III. Edward was determined that his reign was going to be as spectacular as Arthur’s was. He believed in the stories of Arthur and his Knights. He had even started to have his very own Round Table built at Windsor Castle. He also founded The Order of the Garter— which is still the highest order of chivalry that the Queen can bestow. Arthur, whether fictional or not, influenced kings.

So how do we separate fact from fiction?

In our search for Arthur, we are digging up folklore, and that is not the same as excavating relics. We have the same problem now as Geoffrey of Monmouth did back in the 12th Century when he compiled The History of the Kings of Briton. His book is now considered a ‘national myth,’ but for centuries his book was considered to be factually correct. So where did Monmouth get these facts? He borrowed from the works of Gildas, Nennuis, Bede, and The Annals of Wales. There was also that mysterious ancient manuscript that he borrowed from Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford. Monmouth then borrowed from the bardic oral tradition. In other words, he listened to the stories of the bards. Add to the mix his own imagination and Monmouth was onto a winner. Those who were critical of his work were brushed aside and ignored. Monmouth made Britain glorious, and he gave us not Arthur the general, but Arthur the King. And what a king he was.

In our search for Arthur, we are digging up folklore, and that is not the same as excavating relics. We have the same problem now as Geoffrey of Monmouth did back in the 12th Century when he compiled The History of the Kings of Briton. His book is now considered a ‘national myth,’ but for centuries his book was considered to be factually correct. So where did Monmouth get these facts? He borrowed from the works of Gildas, Nennuis, Bede, and The Annals of Wales. There was also that mysterious ancient manuscript that he borrowed from Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford. Monmouth then borrowed from the bardic oral tradition. In other words, he listened to the stories of the bards. Add to the mix his own imagination and Monmouth was onto a winner. Those who were critical of his work were brushed aside and ignored. Monmouth made Britain glorious, and he gave us not Arthur the general, but Arthur the King. And what a king he was.

So is Arthur a great lie that for over a thousand years we have all believed in? Should we be taking the Arthurian history books from the historical section and moving them to sit next to George R. R. Martin’s, Game of Thrones? No. I don’t think so. In this instance, folklore has shaped our nation. We should not dismiss folklore out of hand just because it is not an exact science. We should embrace it because when you do, it becomes easier to see the influence these ‘stories’ have had on historical events.

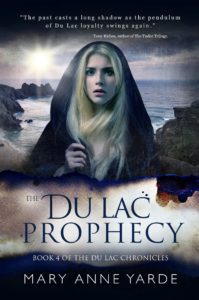

The Du Lac Prophecy

(Book 4 of The Du Lac Chronicles)

By Mary Anne Yarde

Two Prophesies. Two noble Households. One throne.

Two Prophesies. Two noble Households. One throne.

Distrust and greed threaten to destroy the House of du Lac. Mordred Pendragon strengthens his hold on Brittany and the surrounding kingdoms while Alan, Mordred’s cousin, embarks on a desperate quest to find Arthur’s lost knights. Without the knights and the relics they hold in trust, they cannot defeat Arthur’s only son – but finding the knights is only half of the battle. Convincing them to fight on the side of the Du Lac’s, their sworn enemy, will not be easy.

If Alden, King of Cerniw, cannot bring unity there will be no need for Arthur’s knights. With Budic threatening to invade Alden’s Kingdom, Merton putting love before duty, and Garren disappearing to goodness knows where, what hope does Alden have? If Alden cannot get his House in order, Mordred will destroy them all.

BUY LINKS:

Amazon US

https://www.amazon.com/Du-Lac-Prophecy-Book-Chronicles-ebook/dp/B07GDS3HPJ

Amazon UK

https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B07GDS3HPJ/

Amazon CA

https://www.amazon.ca/Du-Lac-Prophecy-Book-Chronicles-ebook/dp/B07GDS3HPJ/

Author Bio:

Mary Anne Yarde is the multi award-winning author of the International Bestselling series — The Du Lac Chronicles.

Yarde grew up in the southwest of England, surrounded and influenced by centuries of history and mythology. Glastonbury — the fabled Isle of Avalon — was a mere fifteen-minute drive from her home, and tales of King Arthur and his knights were a part of her childhood.

Media Links:

Website/Blog: https://maryanneyarde.blogspot.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/maryanneyarde/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/maryanneyarde

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.com/Mary-Anne-Yarde/e/B01C1WFATA/

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/15018472.Mary_Anne_Yarde

Mary Anne Yarde says:

Thank you so much for inviting me onto your fabulous blog!

Mercedes Rochelle says:

With Great Pleasusre!

Geoffrey Tobin says:

The “Dark Ages” are a time obscured by the loss of many manuscripts. Fires like the one in the Cotton Library obliterated the early records of Cambridge University. The desecration of the abbeys by Henry VIII and further destruction during the English Civil War and the French Revolution have removed much from written memory. The wars of the Early Middle Ages and onwards have been very costly to historical manuscripts.

Even so, an insular outlook narrows our window into antique times. Some of Britain’s history has been preserved in Continental records. We can be sure, for example, that the picture of helpless Britons abandoned by Rome around 410 isn’t accurate, for according to Roman records in 451 British archers helped defeat Attila the Hun and around 470 the Britons sent 12,000 soldiers to fight the Visigoths in Berry.

Gildas’s Britain of the mid-500s was ruined not so much by Saxon invaders as by civil wars: his vituperations against British warlords are for moral, not military reasons. Cunoglas, whom he describes using the Bear metaphor, may be Arthur: there’s an old story that Arthur killed Gildas’s brother.

Geoffrey of Monmouth is a different story: reputedly, he, like JRR Tolkien, was the son of an Arthur, and he had a fascination with older British/English history; if he couldn’t find it in ancient manuscripts, he had to make it up.

Geoffrey didn’t have the printing press, but he had one advantage over Tolkien: a true British military hero had visited Monmouth in his father’s lifetime, namely Alan Rufus, Earl of Richmond, hero of Hastings, “flower of the kings of Britain” and, paradoxically, protector of the English as well as bodyguard of the Norman kings.

Geoffrey was conservative in renaming Alan’s family as “King” Arthur’s: Uther (Eudon), Igraine (Orguen), Guanhara (Gunhildr of Wessex) (we know her fictional self in the French form Guinevere), Hoel (Hoel). To the historic Ambrosius Aurelianus he gave the same death as Alan’s paternal uncle Alan III of Brittany: poisoning by a traitor.

Fictional uses aside, Arthur and Uther are both genuine Breton names, attested in legal documents of Brittany in the mid-800s.

Speaking of great British kings, it might surprise, but John Horace Round found that the name Alfred occurs among Breton government officials in the early 800s, before Wessex had a king of that name. King Alfred decreed that Bretons were welcome in his realm, which may be why it remained a popular name in late 11th century Brittany. Most Alfreds in the Domesday Book are known to be Bretons.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

I reckon the isle of Avalon is the Isle of Avallon: check it out in Google Maps. In the last years of the Western Roman Empire it was a military post of their allies, the Burgundians.

Mary Anne Yarde says:

Hi Geoffrey, thank you for taking the time to comment.

You are quite right. We did indeed lose many of our manuscripts due to the points you touched on. With regard to Brittany, many were destroyed during the Viking invasion.

As you so rightly said, Britain was not quite the defenceless country that, for some reason, it is believed to have been after Rome withdrew her forces. But, if we go by what Gildas said, there were some very serious issues facing Britain.

It is said that a wealthy Romanized family from southern Britain wrote an appeal to Consul Flavius Aetius, seeking military aid. They told Aetisu that:

“The barbarians drive us to the sea and the sea drives us back to the barbarians; death comes by one mean or another; we are either slain of drowned.”

But at the time Aetius had more pressing matters with Attila and his Huns.

Gildas goes on to state that Vortigern (overlord) became the High King of Southern Britain. But, he was faced with the constant threat of invasion from the Irish on the western seaboard. The Picts were invading from the north, and in the eastern seaboard, the Saxons were trying their luck. Vortigern turned to his Roman friends for help. But instead of military assistance, Aetius sent Bishop Germanus of Auxerre (The Bishop famous famed for The Hallelujah Victory) and Bishop Severus of Trier, to Vortigern’s kingdom to find out what was going on and report back to him. However, Germanus was more concerned about finding the Pelagian heretics than the threat that Vortigern spoke of. Germanus and Severus took their leave, having done very little. Not knowing what to do, Voitigern turned to two Jute mercenaries — Hengist and Horsa. The Jutes came, they fought, they settled in Kent and it wasn’t long before Vortigern’s relationship with these Jutes started to go terribly wrong. Gildas describes the “Saxon” rebellion as a burning fire:

“Once lit, it did not die down. When it had wasted town and country in that area, it burnt up almost the whole surface of the island, until its red and savage tongue licked the western seas..”

So I think this is where the whole idea of Britain becoming a weak and defenceless country comes from.

If you would allow me to stay with Gildas for a little longer. You are right, Gildas does use his great work — On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain — as an attack at the moral shortcomings of certain warlords. An argument has been brought forward that the reason he does not mention Arthur in his damning sermon was because Arthur, as you said, killed his brother. The way On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain reads I would have thought that it would have been the perfect opportunity for Gildas to attack Arthur. Some say he didn’t include him because Gildas was in so much contempt of Arthur that he left him out on purpose. I am not too sure about that one. Gildas liked to speak his mind.

Uther has very strong links with Brittany, and as you say, names were changed. In Monmouth’s, History of the Kings of Britain, Uther has two brothers — Pendragon and Aurelius Ambrosius. Budic II of Cornouaille in Brittany is said to have married Uther’s sister and so was Arthur’s uncle. But he also married Pendragon’s daughter. It is all a little confusing. Especially when you mix historical figures with legendary ones.

As I said in the post, there are many theories as to who Arthur was and where he came from. Nennius calls him a great general who fought 12 famous battles, the most well known, of course, being at Badon Hill. But then, Arthur isn’t mentioned at all by Bede.

Anyway, I could go on. Thank you once again for commenting and I hope you enjoyed the post.

Cireena Faed Simcox says:

My comment isn’t actually about the content of your article, Mary Ann, but from another very strong oral tradition: – those of woman to woman. I’m not being critical but curious: – was it a deliberate omission and, if so, I expect the next question is, inevitably…”Why?”

To my mind the oral histories, myths and legends passed down through the maternal line in many families/occupations, also helped shape our history, myths, cultural background?

(Even my twitter bio mentions that my curiosity is almost a compulsion; so I reiterate that I’m not critiquing – am genuinely asking.)

Geoffrey Tobin says:

Geoffrey of Monmouth is confusing, I agree: in his story/ies, who is Merlin? Who is Ambrosius Aurelianus?

Alan Rufus’s mother Orguen was a great-grand-daughter of Budic II of Cornouaille.

Alan’s identity itself caused historians much confusion from Wace onwards. He was confused with Duke Alan IV of Brittany. After all, they were close relatives: first cousins on one side and first cousins once removed on the other. Both were great warriors who took part in English invasions of Normandy (1091 and 1106). They both had good reason to wear iron riding gloves (Fergant), namely the proven risk of poisoning by the Montgomery clan.