While researching this novel I had the good fortune to stumble across the book “The Turbulent London of Richard II”—not, as it turns out, because of the content. It was way too specialized for me. But it came with the most awesome fold-out “sketch map of London in the time of the Peasant Revolt” that I photocopied and taped to my wall. It’s still there, three novels later. I spent hours scrutinizing it until I had a faithful understanding of England’s most important city, most of which was still tucked inside of the old Roman walls.

While researching this novel I had the good fortune to stumble across the book “The Turbulent London of Richard II”—not, as it turns out, because of the content. It was way too specialized for me. But it came with the most awesome fold-out “sketch map of London in the time of the Peasant Revolt” that I photocopied and taped to my wall. It’s still there, three novels later. I spent hours scrutinizing it until I had a faithful understanding of England’s most important city, most of which was still tucked inside of the old Roman walls.

This was important, for at the time of the Peasants Revolt, the city officials relied on the wall to keep the rebels out. There were seven gates in the Roman wall: Ludgate (facing west), Newgate (where the prison was), Aldersgate (facing Smithfield), Cripplegate, Bishopsgate, Aldgate (east, facing Mile End), and the Postern Gate at the Tower of London (pedestrian only). The only other way into London was over the London Bridge, which had a drawbridge at the Southwark end. Of course, the mayor of London was dependent on the loyalty of his gatekeepers, and this ultimately failed him. Once Aldgate was opened and the insurgents came pouring into the city from the east, he had no choice but to lower the drawbridge and give passage to the Kent rebels.

London Bridge was a world all its own, populated by every conceivable business except taverns—for they had no cellars. The shops occupied the ground floor with their colorful signs nine feet above the pavement so a horse and rider could pass underneath. Every sign displayed an image representing a trade so it could be identified by anyone, literate or not. The bridge was twenty feet wide, lined on both sides by buildings cantilevered over the edge, supported by huge wooden struts. Each house only occupied four feet of the stone platform; which meant that only twelve feet was left to accommodate the road. Two and three stories high, the houses blocked out the sun like a tunnel, especially since many of the top floors were connected by an enclosed walkway. This would have been the conduit through which thousands and thousands of rebels pushed their way into the city. At this stage of the rebellion they were exhorted by their leaders to be well-behaved, though I can only imagine the trepidation felt by the hapless shopkeepers.

Interestingly, one of the rebels’ first targets was John of Gaunt’s great Savoy palace, which was the most elegant townhouse in all of London. It bordered the river, upstream on the way to Westminster along the Strand. The Strand was the London version of Millionaire’s Row: wealthy riverfront properties free of the stink and pollution of the city. To get to the Strand, you had to pass out through Ludgate then cross the Fleet, an open sewer polluted by the butchers and tanners dumping their refuse into the River Holborn—not to mention the prison sewage. The Fleet in turn poured its stinking offal into the Thames. And that’s not all: at certain docks along the river contained laystalls (think Dicken’s Puddle Dock, at Black Friars). This is where the night soil, or human excrement, was piled up, eventually to be taken away by five barges located downstream. You can just imagine the horrific stench.

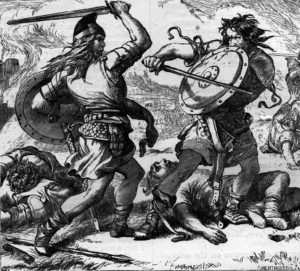

Anyway, the rebels had to pass the famous Knights Hospitaller Temple along the way to the Savoy (they would be back—that’s where the lawyers lived). You also had Durham House (residence of the Bishop of Durham), York House (for the Bishop of York), the convent of the White Friars…you get the idea. I don’t think any of these palaces escaped the attention of the insurgents. Once they destroyed the Savoy—literally, for they accidentally blew it up with barrels of gunpowder, trapping many of the rebels in the cellar—they rampaged their way back into the city, spreading out in their efforts to eliminate the hated foreigners who competed for jobs and took food from their mouths. Oh, and to see how much plunder they could amass.

During the early phase of the Peasants’ Revolt, the king and his few nobles took refuge in the Tower of London, alleged to be invulnerable to attack. And it probably would be, though any fortress is only as strong as its human defenders. While Richard and party were at Mile End negotiating with the rebels on day two, the troublemakers remaining in the city forced their way in and seized the Archbishop of Canterbury and Treasurer Hales, decapitating them in the process. How? No one knows, but since the Tower defenders were commoners, one can only assume they were persuaded to join the cause.

After two days of rioting, the rebels finally agreed to meet King Richard at Smithfield, approached through Aldersgate. Just north of the city walls, Smithfield was an open space so large it would take about ten days for a yoke of oxen to plow it. Every August since the time of Henry I, the famous Bartholomew Fair was held there, bringing people from all over the country. Otherwise, Smithfield was most often used as a horse market, though sometimes it hosted sporting games, tournaments, and even executions. The Scottish rebel, William Wallace, was hanged, drawn, and quartered in this very spot, under the elms in the far northwest corner. This time it was the turn of Wat Tyler, who led his rowdy followers to Smithfield in an attempt to wrest more concessions from the king. Unfortunately for Wat, this would be the site of his untimely end, as well. And in the confusion, the rebels had nowhere to go but north toward Clerkenwell Fields, for the way out was blocked by the Roman wall to the south, the Fleet to the west, and the Priory of St. Bartholomew to the east. A brave and resilient King Richard led the way and the chastened rebels followed. Once they were brought under control, the Essex rebels scattered to the north, but the Kent contingent was led back through the city and over the London Bridge again; this time their behavior was impeccable (under pain of death).

By all accounts, a tremendous amount of damage was done to London during the Peasants’ Revolt, but of course it survived. One wonders why it didn’t go up in flames like the Great Fire of 1666, but perhaps the violence was directed more against people than structures?