Many people get confused when they read that Richard II was the last Plantagenet king. How can that be? During the Wars of the Roses, both the Lancastrians and the Yorkists were Plantagenets. And that’s true. However, Richard II was the last in the direct line—and that’s the difference.

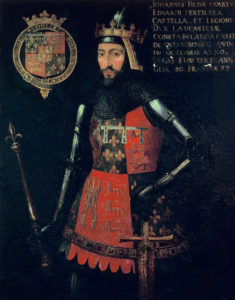

One could almost say that Edward III had too many sons. If his heir, Edward the Black Prince hadn’t died prematurely, all would probably have gone a different route. Lionel, the second son of Edward III (who survived infancy) also predeceased his father, leaving a daughter Philippa from his first wife. It was through Philippa that we have the Mortimers, arguably the true heirs to the throne if you follow the “laws” of primogeniture (see below). The next son was John of Gaunt, the father of the future Henry IV (the Lancastrians). After him came Edmund Langley, later Duke of York (yes, those Yorkists), and lastly, Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester.

What is primogeniture? According to historian K.B. McFarlane, “a son always preferred to a daughter, a daughter to a brother or other collateral.” So the daughter’s heirs should come before the brother’s heirs (hence the Mortimers). Of course, it didn’t always work that way, even among the royals. As far back as King John, we see the youngest brother of a previous king mount the throne rather than the son of an elder brother (Arthur of Brittany—son of Geoffrey—should have ruled if the tradition of primogeniture were followed).

The Black Prince took nothing for granted, and on his deathbed he asked both his father and his brother John of Gaunt to swear an oath to protect nine year-old Richard and uphold his inheritance. Even this precaution didn’t guarantee Richard’s patrimony, and Edward III felt obliged to create an entail that ordered the succession along traditional male lines. This meant that the Mortimers were excluded. It also meant that John of Gaunt was next in line after Richard, and after him, Henry of Bolingbroke. This entail was kept secret at the time because of Gaunt’s unpopularity, and it’s possible that Richard later destroyed at least his own copy. It might have been lost to history until the last century when a badly damaged copy was discovered in the British Library among the Cotton charters (damaged by a fire in 1731). It clearly gave the order of succession as Richard, then Gaunt and his issue, then probably Gaunt’s brothers; parts of the manuscript are lost. According to historian Michael Bennett, “While crucial pieces of the text are missing, it is tolerably certain that the whole settlement is in tail male…”

Why is this important? It’s more than likely that at least members of the royal family knew about the entail. King Richard II and Henry Bolingbroke never got along, and as Richard continued to remain childless, the thought of Henry succeeding him was anathema. He still refused to name an heir, and since he remarried in 1396 the 29 year-old king was still young enough to father a child, even though his new queen was only seven at the time. It’s interesting that he never gave the Mortimer line much credence; he only mentioned them once in his own defense when his barons grew rebellious in 1385: why usurp Richard and replace him with a child? (The Mortimers had a history of dying young and the current heir was just a boy.) Nonetheless, many of his countrymen assumed Roger Mortimer was heir presumptive and didn’t think to question it. By 1397 the grown-up Roger was very popular, but was killed in Ireland shortly thereafter.

Fast forward to Henry IV’s usurpation. Legally, he had a problem. There was another living under-aged Mortimer heir (he quickly took the boy hostage and raised him alongside his own children). Richard abdicated the crown to Henry but only under duress. The new king was advised against claiming the crown by right of arms, because the same thing could be done to him. His reign was riddled with rebellions, and because things didn’t improve like he promised, people started remembering Richard with nostalgia. They wanted the old king back, and rumors of his escape to Scotland only added fuel to the proverbial fire.

Henry IV only ruled for a little over thirteen years, and the last half of his reign he was a very sick man. There were times he couldn’t rule at all and had to depend on his council. His son, the future Henry V, was ready and willing to take over; he even tried to persuade the old man to retire. But that miscarried and Henry dragged himself back into action for a short time, dismissing his son from the council and taking control again. But his days were numbered and everyone knew it. Henry V’s short and glorious reign was cut short by dysentery, and the long and pitiful reign of his infant son Henry VI drove the country into civil war. So much for the Lancastrians.

The Yorkists were descended from both Edmund Langley, the first Duke of York and Philippa, ancestor of the Mortimers. That’s why they felt they had a superior claim to the throne. But by the Wars of the Roses, the Plantagenet line was pretty much diluted. It’s ironic that Henry Tudor, father to the next dynasty, was himself actually descended from a Plantagenet through his mother. Margaret Beaufort was the last surviving member of the bastard line issuing from John of Gaunt (and legitimized by Richard II). It sounds like poetic justice to me.

Vivienne Sang says:

That’s fascinating. I was not aware that the right of females to ascend the throne was denied. I’ve always been interested in that era–The Wars of the Roses. I can’t understand why people in this country are so obsessed with the Tudors (except for Henry Tudor who became Henry VII. He was much more interesting than the others, in my mind).

Mercedes Rochelle says:

I’m with you! The Tudors have certainly been overdone IMHO. Henry VIII was a monster in his old age!