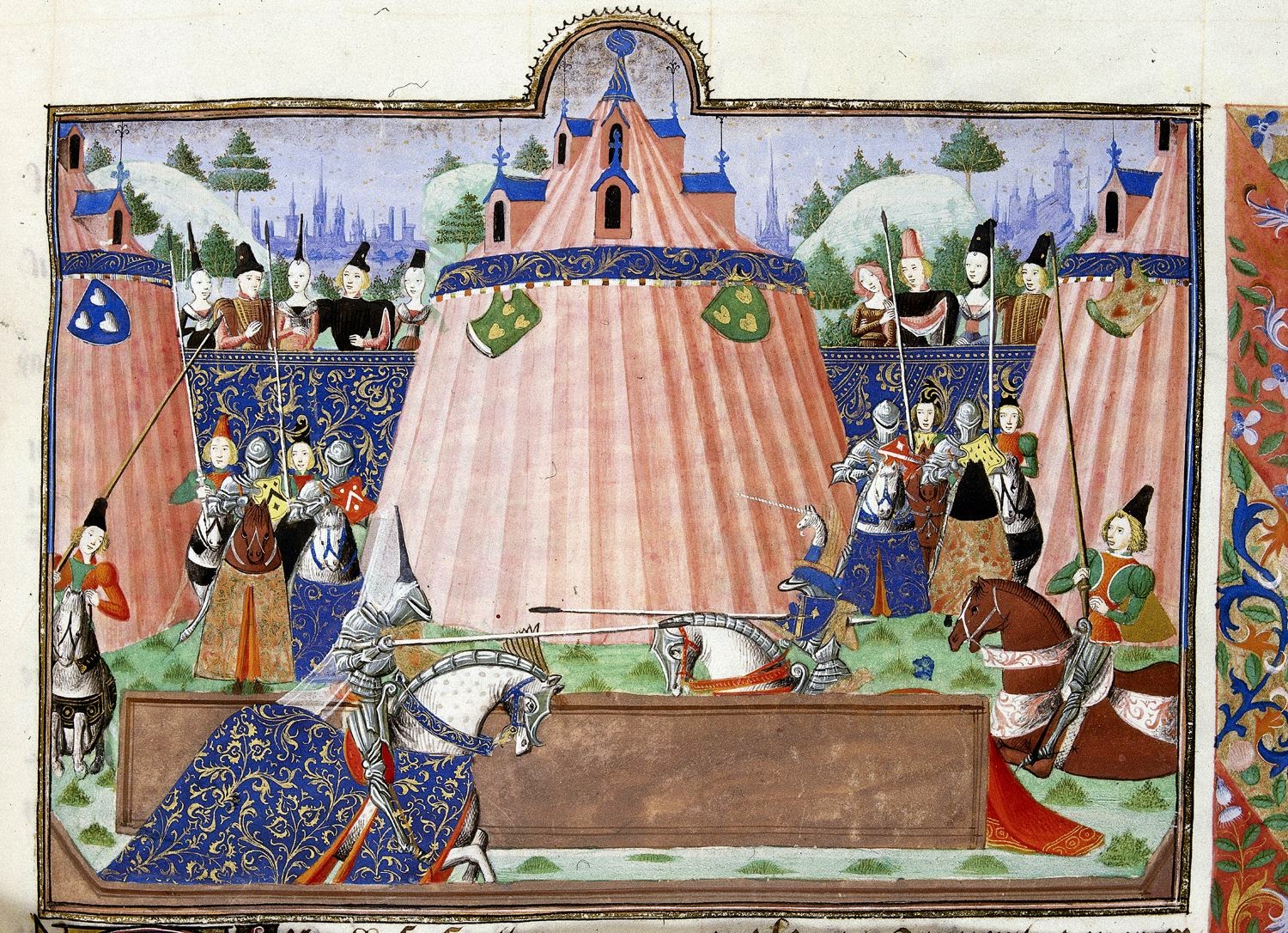

The tournament of Saint-Inglevert, in the Harley Froissart, Harley MS 4379, f. 43r, British Library Creative Commons license

The tournament of Saint-Inglevert, in the Harley Froissart, Harley MS 4379, f. 43r, British Library Creative Commons license

Aside from a slight digression to Scotland in order to prove his manhood, Richard II was not interested in warfare. But there’s no getting away from the fact that the Age of Chivalry had reached its apex by the end of the fourteenth century. When we think of knights armored from head to foot in articulated plate with splendid crests atop their helmets and gay caparisons flowing from their stallions, this is the period that comes to mind. Europe may have experienced a brief hiatus in warfare, but the knights gave themselves plenty of opportunity to excel in arms: the tournament.

I would say the most famous tournament of all time were the Jousts of St. Inglevert, held in 1390 and described in detail by Jean Froissart. Three famous French knights, Jean Boucicaut (soon to be marshal of France), Renaud de Roya, and the lord de Sempy challenged one and all to meet them at St. Inglevert, a religious house between Boulogne on the sea and Calais. This was to be a month-long event, and all of Christendom were keen to attend.

The French knights erected three rich vermilion-colored pavilions. Each was hung with two shields, emblazoned with their arms: one shield represented the “joust of peace”, requiring blunt lances, and the other, the “joust of war” requiring sharpened steel lances. Each challenger (or his squire) was to ride up and touch his shield of preference with a special wand, and the resident herald would record his name, country, and family.

King Richard II did not attend; he was still recovering from the trauma of the Merciless Parliament of 1388. Henry Bolingbroke, on the other hand, led a solid contingent of over one hundred knights and squires, including John Holland, earl of Huntingdon (the king’s half-brother), Thomas Mowbray, the Earl Marshal, John Beaufort, Thomas Swynford, Harry (Hotspur) Percy and his uncle Thomas Percy.

According to Froissart: “Sir John Holland was the first who sent his squire to touch the war-target of Sir Boucicaut, who instantly issued from his pavilion completely armed. Having mounted his horse, and grasped his spear, which was stiff and well steeled, they took their distances. When the two knights had for a short time eyed each other, they spurred their horses and met full gallop with such force that Sir Boucicaut pierced the shield of the Earl of Huntingdon, and the point of his lance slipped along his arm, but without wounding him. The two knights, having passed, continued their gallop to the end of the list. This course was much praised. At the second course, they hit each other slightly, but no harm was done; and their horses refused to complete the third. The earl of Huntingdon, who wished to continue the tilt, and was heated, returned to his place, expecting that sir Boucicaut would call for his lance; but he did not, and showed plainly he would not that day tilt more with the earl.

Sir John Holland, seeing this, sent his squire to touch the war-target of the lord de Sempy. This knight, who was waiting for the combat, sallied out from his pavilion, and took his lance and shield. When the earl saw he was ready, he violently spurred his horse, as did the lord de Sempy. They couched their lances, and pointed them at each other. At the onset, their horses crossed; notwithstanding which, they met; but by this crossing, which was blamed, the earl was unhelmed. He returned to his people, who soon re-helmed him; and, having resumed their lances, they met full gallop, and hit each other with such force in the middle of their shields, that they would have been unhorsed had they not kept tight seats by the pressure of their legs against the horses’ sides. They went to the proper places, where they refreshed themselves and took breath.”

After Holland chose the shield of war, no one else chose the shield of peace for fear of being declared coward. There were lots of sparks flying from helmets, shattered lances, and pierced targets. Most knights ran up to 5 courses. All told, 137 courses were run during the month and all three French challengers survived the ordeal, to their everlasting glory (somewhat the worse for wear but intact). At times they needed a few days to heal from wounds, whereupon their surviving companions covered for them. Henry Bolingbroke was said to have made a spectacular showing and Boucicaut later invited him to accompany him to two crusades.

Not to be outdone, King Richard II hosted another famous tournament at Smithfield in October of the same year. This was the same location where he confronted Wat Tyler during the Peasants’ Revolt nine years previously. Sixty fully-armored knights paraded through the streets from the Tower, down Cheapside to Smithfield, led by sixty ladies mounted on palfreys, richly ornamented and dressed. The ladies led their knights by a silver chain, and all were accompanied by minstrels and trumpets. The king and queen attended, accompanied by dukes, counts, and lords, and after a full day’s jousting entertained their guests with a magnificent banquet. The jousting went on for five days, then the court moved on to Windsor castle.

One of the more interesting jousts was actually held on London Bridge. Many Scots and English participated in the tournament, but the main event was a personal challenge between the English Ambassador to Scotland, Lord Wells, and Sir David de Lindsay, a Scottish knight; they engaged to joust a l’outrance, or to the death. Held before King Richard, the knights ran two courses without incident, and on the third pass Lord Wells was unhorsed. They proceeded to fight on foot and again Sir David held the advantage. But just as the Scot was ready to deliver the killing blow he relented and helped Lord Wells to his feet, gaining the approval of the crowd.

The most famous trial by combat in the fourteenth century was between Henry of Bolingbroke (the future Henry IV) and Sir Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk. Unfortunately, the combat never took place; the King stopped it at the last minute. But the ceremony and protocol were all there; we get a colorful description in the Chronicque de la Traison et Mort de Richart Deux Roy Dengleterre (the author was probably an eye-witness).

According to la Traison, “The lists were to be sixty paces long and forty wide; the barriers seven feet high. The sergeants-at-arms were not to let the people approach within four feet of the lists… the penalty for entering the lists, or making any noise, so that one party might take advantage of the other, was the loss of life or limb, and also of their castles, at the pleasure of the King.” This was serious stuff! Again, according to la Traison, “The weapons allowed by the marshal and constable were the “Glaive”, long sword, short sword, and dagger. The long sword was straight, and called by the French “estoc”, whence estocade, a thrust.”

The King ordered that they take away the pavilions and “let go the chargers, and that each should perform his duty”. Apparently Bolingbroke first advanced a few paces when the King threw his threw his staff (warder) into the list, crying, “Ho! Ho!” For the King to interfere in the duel was not unheard of, though it seems that the crowd was bitterly disappointed to be denied their entertainment; never mind that the fight was to the death. Apparently there were no other amusements on the agenda. The contestants were equally skilled in tournament fighting, and by no means was the result a foregone conclusion. The king withdrew with his council—including Bolingbroke’s father, John of Gaunt—and discussed the matter for two hours while the attendees waited. Finally it was announced that Bolingbroke was to be exiled for ten years and Mowbray for life. From most accounts, the crowd was incensed at Bolingbroke’s treatment; after all, he had done nothing wrong. Few seemed to object to Mowbray’s fate; was he guilty until proven innocent? Nonetheless, everybody went home unhappy, not least of all the main contestants.

Trial by combat seems to have died out by the 15th century, and I haven’t found anything quite as dramatic as this contest. The amount of preparation for such a non-event was staggering. If you happened to be versed in medieval French, you can learn more about tournament ceremonies in this book, reproduced in Google Books: “Ceremonies des gages de batailles selon les constitutions du bon roi Philippe de France”.

Further reading: ROYAL JOUSTS AT THE END OF THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY by Steven Muhlberger, Freelance Academy Press, Wheaton IL, 2012