It’s hard to decide whether Thomas Arundel was a villain or an asset. On the one hand, he was a brilliant administrator. On the other hand, he tended toward despotism. If you read Terry Jones’ entertaining but very biased Who Murdered Chaucer? he was practically the devil incarnate: “The war on heresy, which Archbishop Arundel announced in that winter of 1401, added a new dimension to a period already characterized by fear and intimidation. Gone was the experimental and questioning ‘blue skies’ intellectual environment of Richard II’s court, to be replaced by repression and censorship. The country slid into a regime of Orwellian thought-control and MacCarthyite witch-hunting.” Wow. Colorful though this opinion is, I couldn’t find anyone else who agreed with it—at least to the extent of the archbishop’s oppressiveness. And I looked for it. Yes, anti-Wycliffe dogma was prevalent in Henry IV’s reign—with the approval of the king—and Arundel did attempt to control the curriculum at Oxford with varied success. Yes, the first heretic was burned in Henry’s reign (two total, I believe). But wholesale burning of heretics would have to wait until Mary Tudor.

Thomas Arundel was the younger brother of Richard Earl of Arundel, one of the Lords Appellant in Richard II’s reign who traumatized the king during the Merciless Parliament of 1387. Thomas was serving his first of five stints as Lord Chancellor. He sided with the Appellants against the king, an error he was to pay dearly for ten years later during the Revenge Parliament. By then he was Archbishop of Canterbury, which probably saved his life; Richard shrunk from executing an archbishop. He was sentenced to forfeiture and outlawry instead, commanded to leave the country. A new archbishop was raised in his place.

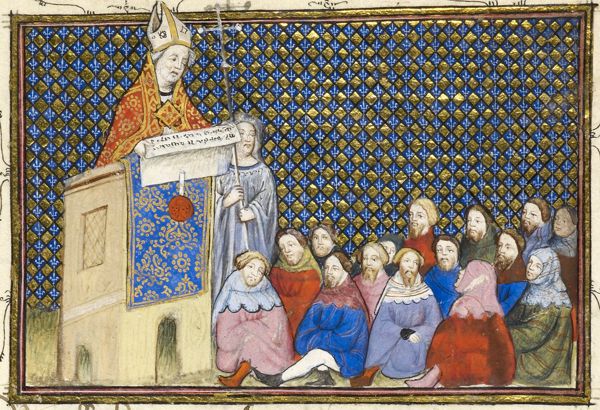

When Richard outlawed Henry Bolingbroke, he demanded that the exiles never contact each other. Of course, who was going to enforce that? Just as soon as Richard left the country for Ireland, Arundel showed up on Henry’s doorstep in Paris and together they plotted Lancaster’s return. Would Henry have had the audacity to take such a risk without Arundel’s prodding? Many historians wonder. Up until that point Henry had been the obedient son, apolitical and relatively carefree (at least, before his exile). Now he was about to launch a major rebellion, with Arundel beside him every step of the way. Not long after they landed in England, Arundel took up his role as archbishop again (without any official appointment) and proceeded to preach against Richard II, allegedly spreading propaganda lies to encourage the people to rebel. You can see the dubious faces of his listeners…

Of course, all went according to plan and Arundel is credited for putting together the means to legitimize Henry’s usurpation. Over the course of his reign, Henry came to depend on him more and more, though at first their association was more political than friendly. But as Henry’s health declined after 1405, he began to spend extended periods of time at the archbishop’s residences. While the king faded into the background, Arundel took a major role in governing the council as well as serving as chancellor from 1407-10 and again from 1412-13. The gap in his official duties was due to the opposition of Prince Henry, who was gaining ascendance as his father was increasingly unable to rule. In fact, the very day Henry V became king, he sacked Arundel and replaced him with his uncle, Henry Beaufort, who was the archbishop’s bitter political opponent. Arundel died a year later and was buried in Canterbury Cathedral. Interestingly, his tomb and chapel were destroyed by Archbishop Cranmer in 1540, presumably as revenge for his repression of heresy.