Richard’s relationship with his uncle, John of Gaunt was fraught with uncertainties and misunderstandings, though throughout it was bound by strict royal precepts. In retrospect, historians have noted that Gaunt’s behavior showed he would never have done anything against the king’s prerogative, no matter how he felt about him personally. But contemporaries—including the king himself—believed otherwise.

This misunderstanding went back to the reign of Edward III. In the old king’s dotage, Gaunt increasingly took on his father’s responsibilities in Parliament, though unlike Edward III, his conduct was overbearing and threatening. The magnates were so afraid that Gaunt might seize the throne for himself that on Edward’s death they hurriedly crowned the 10 year-old Richard rather than risk a regency.

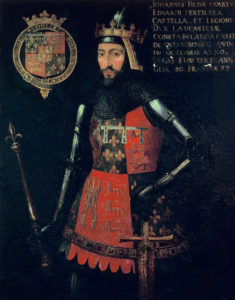

It’s true that John of Gaunt was interested in a crown, but it was the crown of Castile he coveted, in right of his wife Constance. Ever since his marriage to her in 1371 he took on the title of King of Castile and León, and in 1386, circumstances permitted him to go to Spain and make a bid for his crown. He failed, but succeeded in a different way: John married his eldest daughter Philippa to the King of Portugal and his younger daughter Catherine to the future King of Castile. In return for giving up his claim to the Castilian throne, Gaunt accepted a huge payoff of 600,000 francs of gold which was paid in full over the next three years.

But before he took his family to Spain, John had some unpleasant run-ins with young King Richard. In 1384, there was the infamous scene where a Carmelite friar gained access to the king and told him that John of Gaunt was plotting to kill him. In a fit of rage, Richard ordered his uncle’s execution and was only restrained by the urging of his wife and favorites. When an astonished Gaunt stumbled into this frantic scene he forcibly denied the accusation, giving Richard pause and turning all the attention onto the friar. No one ever found out what prompted this accusation, because the Carmelite died under torture that night. But for Richard, his own conduct cast serious doubts on his judgment. Some months later, after a bungled murder plot against Gaunt (planned by the king’s friends), the duke confronted Richard in person and castigated him for permitting such despicable behavior in his court; he stopped short of accusing the king of involvement. Luckily, Richard’s mother Princess Joan was still alive and able to smooth things between them.

The following year, there was a big ruckus between Richard and Gaunt over the upcoming campaign into Scotland. John wanted the king to invade France, but under heavy resistance from the chancellor and Richard’s counselors, his advice was ignored. At first John stormed out of the council, exclaiming that he would have no part of the Scottish campaign. But he soon relented and brought a huge retinue with him, though the antagonism between him and the king would soon rise to the surface again. They fought bitterly once they reached Edinburgh and discovered that the Scots had withdrawn and ravaged Cumberland instead. John wanted to pursue them and Richard stoutly proclaimed that he wouldn’t expose his army to hunger and deprivation for a pointless venture. It didn’t help that his friend Robert de Vere implied that Gaunt hoped the king would meet with an accident along the way. Chase them if you want, Richard told his uncle, you have enough men. I’m going home. Once again, Gaunt gave in and assured the king he was his faithful servant and would follow where Richard would lead. It must have been very difficult for him to swallow his pride.

When the opportunity arose for Gaunt to try his luck in Spain, Richard was so thrilled he gave his uncle a royal send-off, presenting the Duke and Duchess with gold crowns. Finally, his uncle would be out of the way and Richard could rule on his own! Little did he realize that the Duke of Lancaster was the only power propping up his throne. Once Gaunt’s formidable presence was removed, disgruntled magnates—led by Richard’s youngest uncle, Thomas of Woodstock—quickly took his place. There was nothing to hold them back and they immediately went after Richard’s advisors—starting with his chancellor, Michael de la Pole. Over the next two years, powerful nobles known as the Lords Appellant conspired to rid the king of his “bad counselors” and forced him to give up control of his government and accede to their leadership in all things. The judicial murder, outlawry, and dismissal of his friends and advisors left him completely alone and at their mercy. Luckily for the king, the Appellants failed to follow up on their victory. After a year, once it was evident that England was no better off than before, Richard was able to take back full control in a quick coup, reminding the Council that he was well past his majority.

One of the first things he did was recall Gaunt from the continent; Richard had learned his lesson and he needed his uncle’s protection. Although the Duke of Lancaster still had much to accomplish, he obliged his nephew and returned to a hero’s welcome from the king; never again would there be any serious antagonism between them. At the same time, Richard was forced to swallow any antipathy he might have felt against his cousin Henry of Bolingbroke, who was one of the Lords Appellant, albeit an unenthusiastic one. Any retribution against Henry would have to come later, after his father was dead.

It took several years for Richard to feel comfortable enough to launch his retribution against the Lords Appellant, and when it finally came about in 1397 it all happened like a cyclone. Richard’s primary targets were Thomas of Woodstock the Duke of Gloucester (and Gaunt’s younger brother), Richard Earl of Arundel, and Thomas Beauchamp Earl of Warwick. John of Gaunt, as Lord High Steward of England, presided over the Parliamentary trials of the king’s great enemies. He was spared the litigation against his brother; Gloucester died mysteriously while in prison at Calais and Gaunt seems not to have made a fuss over it—at least not in public. Arundel, on the other hand, was a bitter enemy of Gaunt. Although he put up a lively defense, he was treated most harshly by the Duke of Lancaster. Bolingbroke threw in his two cents as well, reminding Arundel of treasonous statements—even though ten years previously he had been on Arundel’s side.

But Henry of Bolingbroke would not escape the king’s retribution. The following year Bolingbroke faced his fellow Appellant Thomas Mowbray in trial by combat at Coventry. This is another story, but suffice it to say that when the king interrupted the tournament (as portrayed by Shakespeare), he decided to exile both parties—Henry for ten years, and Mowbray for life. Richard made this announcement after consulting with his Council for two hours; Gaunt was among their number and gave his assent. Why did he do this? Some said he disapproved of his son, but I find little verification of this in his biographies. Perhaps he thought to send his son safely away from all the scheming and back-stabbing in Richard’s court. Perhaps he had no choice. Regardless, Henry left the country with a heavy heart, for he knew he would probably never see his father again. And so it was; Gaunt died just a few months later.

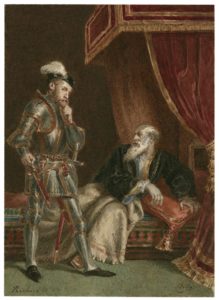

It was said that King Richard visited Gaunt just before his end. Shakespeare had him gloating over the sick old man, but I don’t think it happened that way. At least on the surface, he and his uncle had an amiable relationship the last several years. Once Gaunt was back on the scene, there was no way the Lords Appellant could start up their trouble-making again, and Richard knew it. I do believe he was waiting for his uncle to pass on before moving to his next agenda: eliminating the threat of the overpowerful Lancastrians. But that, too, is another story.

suzanne says:

Thanks very informative article, about the complex relationship between Richard ii and john of Gaunt.

Michael W. Cox says:

Excellent article; thank you.