Tostig left England in November of 1065 after the disastrous Northumbrian rebellion. While waiting for Harold to set everything straight, it soon became clear that his brother was not going to stand up for him, fight for him, or even defend him in counsel. Harold gave in to every rebel demand including Tostig’s exile from the earldom and even the country. Tostig felt betrayed, Edward was despondent, and the queen shed a great many tears. Although the king did not agree with the outlawry—he even insisted they call out the Fyrd to put down the rebellion—his wishes were disregarded. In the end Edward acquiesced to the forces set against him, and he unwillingly sent Tostig off with gifts and words of regret.

Historian Ian Walker tells us that Tostig was outlawed “apparently because he refused to accept his deposition as commanded by Edward”. However, historian Emma Mason said “Tostig did go into exile, but this was his own decision.” So from the very beginning of his exile, Tostig’s actions were debated.

He may have paid a farewell visit to his mother in Bosham, but by Christmas he had landed in Flanders with his family and close associates. Earl Baldwin, his brother-in-law, received them graciously and settled Tostig at St-Omer with a house and an estate, revenues, and even a contingent of knights to command. This wasn’t such a bad state of affairs for an exile, but it was only temporary, used as a base to gather information and collect mercenaries.

King Edward’s rapid decline has been associated with Tostig’s exile; he may even have had a stroke when he discovered that his rule was breaking down in the north. I would imagine that Tostig was shocked by the king’s death, but was he shocked also to learn that Harold took the crown? Did this alter his plans any, or did he always intend to force his way back? After all, Godwine was successful in doing this very thing in 1052 (with Harold’s help); Earl Aelfgar regained his earldom twice by invasion. Tostig was just following a successful strategy to retrieve his fortunes; perhaps he would have expected Edward to acquiesce. On the other hand, with Harold as King his motives took on a more sinister cast.

In the opening months of 1066, King Harold had much on his mind, not the least of which was the unrest in Northumbria. He was even obliged to travel to York (in the winter), to convince the recently pardoned rebels that his motives were unchanged. It’s entirely likely that he chose this high-profile visit to marry the sister of Edwin and Morcar at York Cathedral. Apparently the new king won over the suspicious Northumbrians, and by spring he returned to Westminster for Easter Court. Harold was famed for his diplomacy, but in all this maneuvering I can find no mention of any effort to reconcile with Tostig. Nonetheless, if Harold thought to hold England together by accepting Edwin and Morcar’s control over the north, he was destined to find that losing his brother’s support made things infinitely worse.

What was Tostig doing all this time? It is possible that his first step was a visit to Duke William, who was probably already deep into his plans to invade England. I can’t image what he could have offered the Duke aside from a small fleet supplied by his father-in-law, but it does seem like the most onerous insult he could have offered Harold. Whether he made this visit early in the year or in late spring, it seemed that Duke William didn’t have any particular use for him (though perhaps he encouraged Tostig to cross over in May as a kind of forward movement).

Conversely, Tostig may not have visited Normandy at all. It’s not impossible that he used the winter months to cultivate likely allies in the north. As the popular story goes, Tostig first went to Sweyn Estridsson’s court in Denmark and tried to talk his cousin into invading England. After all, the Danish King was the grandson of Sweyn Forkbeard, so he was in line to the throne of England. But after 15 hard years of conflict with Harald Hardrada, Sweyn was exhausted and so was his treasury. He offered Tostig an earldom in Denmark, but Tostig spurned his suggestion and the two parted company with hard feelings on both sides.

Disappointed, Tostig went on to Norway and gave Harald Hardrada such a pep talk that the formidable king was chomping at the proverbial bit. According to Snorri Sturleson in HEIMSKRINGLA, Tostig assured Harald “If you wish to gain possession of England, then I may bring it about that most of the chieftains in England will be on your side and support you.” This sounds a little delusional considering recent events, but how was Hardrada to know the difference? But Tostig wasn’t finished; he had some diplomatic skills of his own. He added: “All men know that no greater warrior has arisen in the North than you; and it seems strange to me that you have fought fifteen years to gain possession of Denmark and don’t want to have England which is yours for the having.” What self-respecting Norseman could resist that line of reasoning?

Snorri has this conversation take place in the winter, which gave Hardrada the spring and summer to raise his army. However, not all historians agree with this scenario. The venerable Edward A. Freeman concluded that there wasn’t enough time for Tostig to make the voyage and for Hardrada to raise an army. He concluded that Hardrada had planned the campaign on his own and Tostig joined up with him after he made his move. It has also been suggested that Tostig sent Copsig, his right-hand man in his old earldom, as an ambassador to Norway to plan the invasion and didn’t meet Harald in person until later.

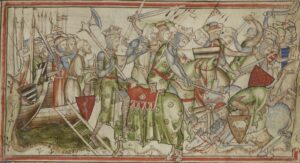

Regardless, Tostig was ready to make his own move in May. Was his purpose to draw Harold out before he was fully prepared? Or was he simply making his own bid for power? The timing seems odd, but he certainly caused a stir. Gathering his little fleet of Flemish and possibly Norman mercenaries, he sailed across the Channel and landed on the Isle of Wight. Here he collected supplies and is said to have forced many of the local seamen to join him with ships. Thus reinforced, he proceeded to plunder eastward along the coast as far as Sandwich, where he expanded his fleet to sixty ships, either voluntarily or by coercion. But by then, King Harold was on his way to stop him, so Tostig made haste to sail off and try his luck farther north along the coast.

Intent on plunder, Tostig entered the Humber and ravaged the coast of Lindesey in Edwin’s earldom of Mercia. But the northern earls were ready for him and drove his little fleet away. At this juncture, most of his allies (volunteers or impressed into service) melted away, and he limped off with only twelve of his original sixty boats in tow. Apparently this setback took the heart out of Tostig’s enterprise—for the moment—and he took refuge with his good friend and sworn brother Malcolm Canmore of Scotland. Always happy to cause trouble on his southern border, Malcolm offered Tostig his protection for the whole summer of 1066. Presumably Tostig sent messages back and forth from there to Hardrada, and he may have attracted some Scottish mercenaries to his cause.

Whether Tostig went to Norway in 1066 or not, historians agree that he spent the summer at King Malcolm’s court in Scotland and joined up with Hardrada after Harald dropped off his queen in the Orkneys and came south with the Orkney Earls. Some think Harald stopped at Dunfermline where Malcolm and Tostig waited. William of Malmesbury thought that Tostig joined Hardrada and pledged his support when the Norwegians reached the Humber, which is very late in the story. Regardless, by that point Harald Sigurdsson was clearly in charge of the expedition, and Tostig was his subordinate.

The first resistance was from Scarborough, North Yorkshire, a town built into the hills that faced the ocean. The locals put up a stout resistance and seemed to drive the invaders away. False hope! Hardrada landed farther down the coast and made his way to the top of the cliffs overlooking the town. The Nowegians put together a huge bonfire and began tossing flaming brands onto the roofs of the houses. Before long many of the buildings were on fire, and the populace surrendered, to no avail. It’s possible that this and other coastal incursions triggered the messages for help that made their way to King Harold; the timing would have been around the second week of September.

The Battle of Fulford was fought on the 20th of September. At this late date (right before the battle) it’s also possible the first messages were sent south. By then, presumably, Tostig’s presence in the Norwegian force was detected, and Harold would have been informed of his brother’s treachery. I wonder how he took the news? Or was Tostig’s behavior a forgone conclusion? Only the historical novelist is free to make that guess, and I am tackling this scenario in my upcoming novel, FATAL RIVALRY.

Sources:

Harold, The Last Anglo-Saxon King by Ian Walker, 1997

Heimskringla: The History of the Kings of Norway by Snorri Sturluson, 1964

History of the Norman Conquest of England by Edward A. Freeman, 1875

The House of Godwine: The History of a Dynasty by Emma Mason, 2004

Geoffrey Tobin says:

November 1065? On reflection, that’s an interesting date.

Alan Rufus may have gone to England with Earl Harold after the Breton-Norman War (that is, the War of the Coalition against Conan II) in which Harold, William and Alan all participated.

According to the Bayeux Tapestry, Alan was William’s emissary to Count Guy of Ponthieu for Harold’s transfer, and he was present when Harold swore his infamous oath.

Both the BT and the Little Domesday Book place Alan in south-east England on the day when King Edward died – he’s identified by a Breton rebus (“the red fox”) at Edward’s funeral and by name as Lord of Wyken in the Parish of Bury St Edmund in Suffolk.

Under King William, Alan retained Orm and the Sons of Gamel as local lords in Richmondshire.

Orm and Gamel were the two men who complained to Edward about the way Tostig governed Northumbria.

After the scenes of Harold’s coronation, the appearance of Halley’s comet, and a man catching Harold’s ear, the Bayeux Tapestry shows “an English ship” arriving in Normandy. This, I think, may be Count Alan returning to report to Duke William.

According to , it was visible from January 1066 until 25 March 1066 (when it was closest to the Sun).

When Tostig visited William in early 1066, was Alan back from England yet or not?

Geoffrey Tobin says:

The dates for the visibility of Halley’s comet are from the Wikipedia article on it.

gmail.org.in says:

Veгy interesting subject, thank ʏou for putting up.