It seems that at some point in every reign, political factions grew up around the king. Sometimes they were minor annoyances and could be ignored. Often they turned toxic—especially when a baron started to throw his weight around. Occasionally the overmighty baron was a member of the royal family, as in the case of Richard II, and he was able to attract powerful friends. As the great historian Kenneth McFarlane put it*: “The nuisance of the overmighty subject was in fact a feature of the rule of weaklings and vanished with the accession of those who had the personal authority to deal with it…To Edward III, Henry V, and Henry VIII the problem did not exist; to Edward II, Richard II, and Henry VI, it was insoluble.” This seems harsh, but I can’t argue with it. The court was more dangerous to King Richard than it was to his subjects.

Of course, during the first ten years of Richard II’s reign the country had to deal with his minority; that didn’t help matters. There was no regent—only a continual council. How can a testy teenager gain control over his opinionated uncles? During the early part of his reign, Richard mistakenly saw John of Gaunt as his primary antagonist—actually, Gaunt had managed to rub almost everybody the wrong way until he gained some humility after his debacle in Spain. Once Gaunt had left the country to chase his crown of Castile, his younger brother the Duke of Gloucester stepped forward, and Richard found himself challenged by an even more unscrupulous opponent. This is when the real trouble began.

Up until then, King Richard was content to surround himself with a tight-knight group of friends and confidants. That in itself might not have rankled, except that he shut himself away from those who considered themselves his proper advisors. The young Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford emerged as the most obvious scapegoat; Richard was very attached to him and it was rumored there might have been some unsavory behavior, reminiscent of Edward II. Also, that commoner Sir Simon Burley, Richard’s chamberlain, kept a firm control over access to the king’s inner chambers. The overmighty barons felt excluded. Something had to be done.

So in these critical first ten years, the faction against the king gained ground, and those faithful to Richard remained a pitiful minority. The Duke of Gloucester joined forces with the irascible Earl of Arundel and the Earl of Warwick; soon they gathered their retainers together and marched on London. Although they insisted that Richard get rid of his bad advisors, the king demurred while Robert de Vere attempted to raise an army to defend him. This perceived betrayal was enough to persuade Henry Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray to join the Lords Appellant, as they all became known.

At the time, the king had no standing army; he was totally dependent on his nobles to do his fighting for him. Who would have been on his side? Already Robert de Vere’s army had surrendered almost without a fight; the Earl of Oxford had no experience in warfare. The Duke of York, Richard’s other uncle, was notoriously ineffectual and could only offer moral support. John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, was in Spain. That’s it for the Dukes; there were only three—all Richard’s uncles. How about the earls? Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland was far in the north; he didn’t get involved. John Holland, Earl of Kent and Richard’s half-brother, was with Gaunt in Spain. Roger Mortimer, Earl of March was in Ireland. Michael de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, was on the run. The last four earls were Appellants. That’s it. Richard was alone.

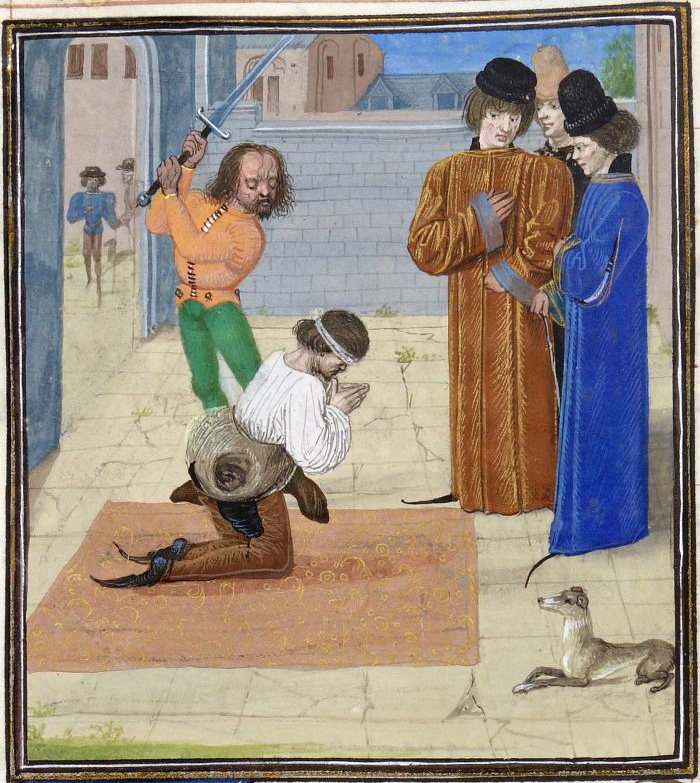

After making short work of de Vere, the Appellants closed in on Richard who had taken refuge in the Tower. There was no way out; the king was their prisoner. It was their moment of triumph and they didn’t hesitate to threaten his crown. What could he do? Richard was forced to bend to their will, sacrificing all his supporters. Burley was executed, along with at least eight others, including Chief Justice Tresilian and ex-mayor Nicholas Brembre. Queen Anne begged on her knees for Gloucester to spare Burley, but to no avail. Servants and knights of the chamber were imprisoned or exiled. The Ex-Chancellor, Michael de la Pole, was the lucky one. He found refuge on the Continent and was joined by Robert de Vere. By the time Richard’s government had been purged, the king had no one to turn to except his wife.

The desolate King Richard spent a year licking his wounds before daring to step forward. But step forward he did. After all, he was twenty-two, and no one could deny it was time to declare his majority. By then, the Lords Appellant had lost interest in governing. After all, they had achieved their goal and their attention was demanded elsewhere. The transition to Richard’s full control was smooth and effortless, and the king had learned his lesson—or so it seemed. For the next seven years, England experienced a rare stretch of peace and prosperity.

But it was not destined to last. Richard had learned an even better lesson from the Lords Appellant. He determined that never again would he find himself alone and defenseless. It was time to retain some men of his own, and he started with the Cheshire Archers. Oh, dear. It was not going to end well…

On to THE KING’S RETRUBITION.

*McFarlane, K.B., THE NOBILITY OF LATER MEDIEVAL ENGLAND, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1973, p.283.