Henry Percy, father and son, were larger than life. The Percys went all the way back to the Norman Conquest, but it wasn’t until 1377 that Henry Percy became the first Earl of Northumberland—at Richard II’s coronation, no less. It took eleven generations to get there, but Henry Percy had arrived. It seems that much of his early good fortune can be attributed to John of Gaunt. He served as Gaunt’s right-hand man during the hundred years’ war. While Gaunt was regent during the end of Edward III’s reign, he was badly in need of allies and made Percy Marshal of England—one of the four great offices of state. The marshal’s job was to keep the peace within the Verge—a shifting twelve-mile radius of the king’s presence. Matters got ugly when Gaunt tried to extend the marshal’s jurisdiction into the city (replacing the mayor), even if it was outside of the Verge. The Londoners were furious at the potential loss of their liberties.

Shortly thereafter matters reached a climax when John Wycliffe—an academic theologian challenging the Church’s doctrines and authority—was summoned to answer for his anti-clerical views. This happened on 19 February, 1377 at St. Paul’s during a Convocation led by William Courtenay, Bishop of London. Matters grew ugly very quickly and Gaunt and Percy found themselves at odd with a rioting mob. They had to escape the city to save their skins, taking refuge in Kennington with Prince Richard and his mother, Joan the Fair Maid of Kent. Not an auspicious beginning!

It was five months after this fiasco that Percy was made earl. At the same time, he was created Warden of the East March of Scotland and gave up his Marshal’s baton. A few months later he was created Warden of the West March as well. This pretty much set him up as ruler of the North, for he was far away from the center of government and the rest of the country trusted him to control the borders. After all, he knew the peculiarities of this strange environment, where blood-feuds were expected, border raids were common, and local gangs called all the shots. Percy’s main antagonist was the Scottish Earl of Douglas, Warden of the Marches on the other side of the border. Their own personal feud became disruptive enough that King Richard decided to commission John of Gaunt as King’s Lieutenant in the Marches, placing the Duke in a superior role to the Warden and fatally poising his relationship with Percy.

Matters came to a head in 1381 during the Peasants’ Revolt. Gaunt was in Scotland at the moment, and when he heard of the uprising he hurried south, pausing at Alnwick Castle—only to be refused entrance. In fact, Gaunt was forbidden to enter any of Percy’s castles; the earl used the specious excuse that King Richard had sent orders forbidding entry to anyone unless under the king’s license. The implication was that Gaunt might be leading a rebel army of his own. Humiliated, the Duke had to take refuge in Scotland until the revolt was over, and his ire precipitated such a feud between him and Percy that it almost came to civil war. Their argument was eventually patched up, but things were never the same between them.

And so, eighteen years later, when Henry Bolingbroke landed at Ravenspur with a handful of followers to reclaim his rights, it was by no means certain that he would be able to rely on Percy’s support. The returning exile continued north to Bridlington, due east of York. Once there, he was surprised by a visit from Henry Hotspur (the younger Percy), who could easily have arrested him and ended the whole rebellion on the spot. But he didn’t. The Percys were having their own little spat with King Richard, who was demonstrating uncomfortable tendencies to diminish their power. They did not accompany the king to Ireland, though historians are unsure whether they refused to go on principle, or were they merely protecting the borders?

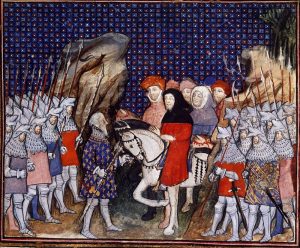

It didn’t take long for the Percys to throw their weight behind Lancaster (John of Gaunt had died four months earlier). It seems relatively certain that they expected Bolingbroke to show his gratitude; after all, without their assistance, he probably would not have succeeded in his bid for the throne. Not only did Percy furnish the bulk of Henry’s army, he was personally responsible for persuading King Richard to give himself up to Bolingbroke’s tender mercies. As soon as the king was safely removed from Conwy Castle, Percy betrayed Richard’s trust, surrounding him and his handful of companions with a hidden company of men-at-arms. The end justified the means! Percy was working for Henry Bolingbroke now, who had already granted him (under his Ducal seal) the Wardenship of the West Marches. The appointment may have been somewhat irregular—this was the king’s grant—but it demonstrated Henry’s commitment. More commissions were guaranteed to follow.

And indeed they did. After the usurpation, King Henry was totally reliant upon the Percys to control the Scottish border and North Wales for him. Whether he wanted to or not, Henry was obliged to appoint them to key positions. In addition to his wardenship, Percy was made Constable of England. Hotspur was made Warden of the East March and given the lordship and castle of Bamburgh. He was also appointed Justice of North Wales and Justice of Chester and given constableship of the castles of Chester, Flint, Conwy and Caernarfon as well as the lordship of Anglesey.

Unfortunately, this was not to last. Like his predecessor, Henry IV saw the risk of entrusting too much power to the Percys. Besides, there was another, more tractable earl he could rely on: Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland. Neville had recently married Henry’s half-sister Joan Beaufort, which brought Westmorland into the royal family. His clan, too, had been in the North for generations, although they did not exert the influence that the Percys employed. Not yet, anyway.

Little by little, King Henry awarded Westmorland land and commissions. He was made Marshal—Percy’s former position—and granted the Honour of Richmond for life. The king even took the Keepership of Roxburgh away from Hotspur (who was supposed to hold it for life) and granted it to Westmorland. Then, to add insult to injury, the king promptly reimbursed Neville his expenses while owing the Percys upwards of £20,000 for their services (roughly 29 million dollars in today’s money)—and making excuses for nonpayment. Needless to say, the Percys took this slight personally.

Nonetheless, they continued to protect the North. In September of 1402, the Scots came across the border in a furious chevauchée all the way to the Tyne. Unable to stop them, Hotspur raised a force to block their return to Scotland. Loaded with plunder, the invaders were intercepted at Homildon Hill, and a great battle was fought. It was a disaster for the Scots. A large number of captives were taken, including the Earl of Douglas, four other earls and at least thirty Scottish knights. It was a tremendous victory for the English, in contrast to the humiliating failure King Henry had just experienced in Wales.

The king’s reaction was less than gracious. Rather than award the Percys, Henry demanded that they turn over the hostages, with the understanding that they would be suitably compensated. It was his right as king, but he couldn’t have made a worse miscalculation. Although Percy senior complied, Hotspur adamantly opposed him. King Henry had refused to pay a ransom for Hotspur’s brother in-law Edmund Mortimer—held hostage by the Welsh—and Hotspur saw this as double treachery. He and the king nearly came to blows, and if the chroniclers can be believed, Hotspur stormed out of the room, declaring “Not here, but in the field!” This was the last time they saw each other alive.

Peter Jordi says:

Hi

I’m trying to get in contact with Ralph Murphy, the author of a book concerning his relation, Captain John Norwood VC. In particular, I am trying to establish the whereabouts of the actual diary of Captain Norwood in respect of the Boer War period and the entry in it concerning the wounding of Trooper Sibthorpe. I have been researching Sibthorpe and wish to obtain more information about him. Could you please provide me with Mr Murphy’s email address?

Best regards

Peter Jordi

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Hi Peter,

I will send your comment to Ralph along with your email.

Thanks