Henry IV’s relationship with the Percys went sour pretty soon after his coronation. He knew that he owed his crown to his northern earl; he also knew that an overly-powerful magnate was a recipe for trouble. So it wasn’t long before the king attempted to mitigate their dominance by promoting their rival, the Earl of Westmorland, who happened to be his brother in-law.

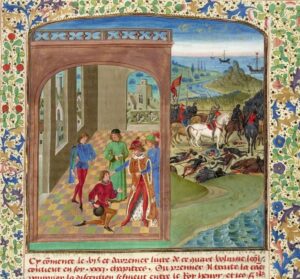

Matters came to a head after their decisive victory at Homildon Hill, where they decimated the Scottish aristocracy. Many were killed, even more were taken hostage—among them the powerful Earl Douglas. Stung by their prowess—in contrast to the humiliating failure he had just experienced in Wales—King Henry demanded they turn over their hostages. It was his right as king, but he couldn’t have made a worse miscalculation. Although Percy senior complied, his son Hotspur adamantly opposed him. King Henry had refused to pay a ransom for Hotspur’s brother in-law Edmund Mortimer—held hostage by the Welsh—and Hotspur saw this as double treachery. He and the king nearly came to blows, and if the chroniclers can be believed, Hotspur stormed out of the room, declaring “Not here, but in the field!” This was the last time they saw each other alive.

Although Henry tried to make amends by awarding lands in Scotland to the Percys—most of which happened to belong to Douglas. It was truly an empty gesture because they had to conquer those territories first. But, as they were acquisitive souls, the Percys decided to give it a try. Hotspur soon laid siege to Cocklaw Tower in Teviotdale, deep into Douglas territory, thinking this would be an easy target. It wasn’t. He was soon frustrated and negotiated a six-week truce, coming back to England with another idea in his mind. Why not take advantage of the truce and launch an offensive against the king?

I believe Hotspur caught his father by surprise. He must have been harboring resentment against the king that wouldn’t go away. Leaving his father to guard the border, Hotspur went to Chester and started raising an army against King Henry; the men of Chester were among King Richard’s most favored subjects and they were hostile to the usurper. They responded enthusiastically, especially as Hotspur promised that Richard would return from exile in Scotland and lead them into battle. Even when Hotspur later reneged on his promise, they agreed to fight anyway. With the help of Hotspur’s uncle Thomas, who left Prince Henry’s service with all of his troops, the rebels made for Shrewsbury, where the Prince was understaffed and vulnerable. They might have gotten young Henry into their hands, too, except for the unexpected arrival of the king, who forced them to battle.

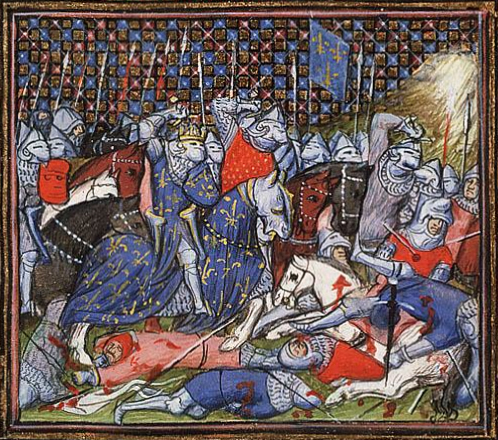

The Battle of Shrewsbury was the most serious threat to King Henry’s reign, and it was a very close call. This was the first time English archers faced each other across the battlefield. Only Hotspur’s death turned the tide; up until that point no one knew who was winning. Would the presence of Earl Henry Percy have made a difference? Almost certainly. Historians debate the reason why he was absent. Some thought his presence was never planned, although he did belatedly start south to support his son. Some thought it was Hotspur’s fight. Others blame Hotspur’s impetuousness and claim he “jumped the gun” so to speak, and screwed up the timing. Shakespeare said Percy was ill and couldn’t make it. Whatever the reason, Henry Percy was devastated by his son’s death; he was never the same man afterwards, and was pretty much driven by the need for revenge.

King Henry was set on punishing Percy, but because the earl wasn’t directly involved he was obliged to wait until the next Parliament. Unfortunately for the king, the lords were on Percy’s side and their response was merely to charge him with “trespass”—in other words, distributing his badge illegally. Percy was restored most of his lands, but the king refused to reinstate his wardenship or the constableship. The earl was in disgrace.

This unfortunate state of affairs lasted another two years. The king appointed his son John as Warden of the East March toward Scotland and Westmorland became Warden of the West March. Percy licked his wounds for a while before coming up with a new plan. In conjunction with Owain Glyndwr, the wily Prince of Wales, and Edmund Mortimer, uncle of the “true” heir to the throne (the child Earl of March), he concocted a new rebellion, this time originating in the North. Most of his supporters were in Yorkshire; as far as the Northumbrians were concerned, they weren’t quite as interested in rebelling against the king and didn’t respond enthusiastically to his overtures. No matter; Percy was on a mission.

Richard Scrope, Archbishop of York added his voice to this uprising. Once again, historians are divided as to whether Scrope went along with Percy, or did he devise a disturbance on his own that happened to correspond with Percy’s rebellion? The timing certainly favored the former explanation. Working the citizens of York into a righteous frenzy, Scrope led a large assembly to Shipton Moor, a few miles from the city. They were protesting high taxes and intolerable burdens on the clergy. The rebels were not a fighting force; they were local citizens. Nor did they possess cannons or instruments of war. The archbishop insisted that their intentions were peaceful. Some historians suggest that their purpose was to add legitimacy to Percy’s rebellion, which was to swing south and supplement its numbers with Scrope’s insurgents. But unfortunately for the archbishop, the expected rebel army never materialized and he was caught holding the proverbial bag.

The lynchpin of Percy’s rebellion was capturing Westmorland in advance, thus removing the only man capable of stopping him. But someone warned the Earl in time and he got away, foiling Percy’s plot. There was no “Plan B”. Had the Earl of Northumberland lost his nerve? He told his followers he was going to Scotland for help and bolted, leaving all of his co-conspirators to their own devices. Scrope wasn’t even warned about the change of plans. So when the Earl of Westmorland mopped up after the aborted rebellion, his ruse was to convince the archbishop he would present their reasonable manifesto to the king, and that the Yorkist citizens should just go home. Naively, Scrope agreed, only to find himself arrested along with his confederate, the doomed Thomas Mowbray, son of King Henry’s old enemy.

Who would have thought that the king would execute an archbishop? Scrope and Mowbray didn’t stand a chance. Once he arrived at York, the king rushed his judges through a trial and condemned the leaders, deaf to pleas from the Archbishop of Canterbury that he should refer the case to the Pope. Henry was not to be reasoned with, especially since Percy had slipped through his fingers once again. This time, there would be no Parliament to get in his way. He brought his cannons with him and besieged Percy’s castles all the way up to Berwick, ensuring that the traitorous earl would find no further refuge in England.

For the next three years, Henry Percy wandered through Wales and France, looking for support against the usurper king. But it was to no avail. The great earl had lost all credibility. When he was finally lured back into England with a new offer of support, he snatched at the opportunity, campaigning into Northumberland in the midst of the most bitter winter in living memory. Gathering a motley crew of country folk and local knights, Percy was confronted with a local detachment led by the very man who invited him south. He had nothing to lose and chose to risk everything on a last battle, meeting his pitiful end at Branham Moor, about ten miles from York, on 19 February, 1408. His head was delivered in a basket to King Henry and his body was quartered as befitted any traitor. Eventually his parts were collected and the great earl was reunited with his son, laid to rest near the great altar at York Minster.

But the Percy line was not extinct by any means. When Henry Percy took refuge the first time in Scotland, he brought with him Hotspur’s young son Henry, who spent the next ten years a virtual hostage. Henry V decided that a Percy in the North would suit his purposes, and the king arranged Henry’s return, creating him 2nd Earl of Northumberland in 1416. Part of the deal was young Henry’s marriage to Eleanor, the daughter of Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland. And so they came full circle. But never would they achieve the fame of the first earl, their doomed ancestor.