On my first trip to England I was terribly excited to tour the battlefield of Hastings, and we headed to the town of that name in our rented car. Mind you, this was in the early ’90s, before the internet and easy access to unlimited information. I had all my sketches of the battle itself, but I was kind of unclear as to exactly where it was fought. I figured I’d see signs pointing the way, or something…actually, I’m not sure just what I expected to find! What I didn’t expect was to find the town of Hastings, and no mention of a battlefield anywhere. What a panic!

On my first trip to England I was terribly excited to tour the battlefield of Hastings, and we headed to the town of that name in our rented car. Mind you, this was in the early ’90s, before the internet and easy access to unlimited information. I had all my sketches of the battle itself, but I was kind of unclear as to exactly where it was fought. I figured I’d see signs pointing the way, or something…actually, I’m not sure just what I expected to find! What I didn’t expect was to find the town of Hastings, and no mention of a battlefield anywhere. What a panic!

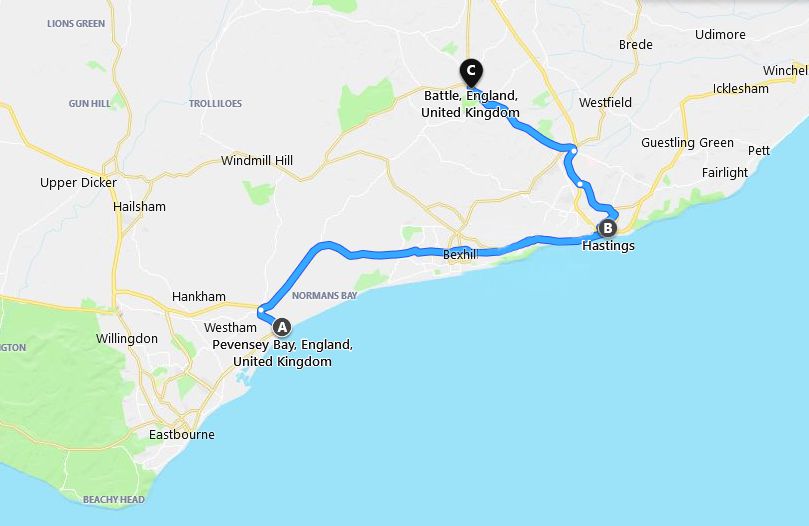

Luckily, Brits and Americans DO share a common language, and a kind soul pointed us in the right direction. We eventually found our way to the town of Battle, a little over 6 miles to the northwest of Hastings. Needless to say, it’s called Battle for a reason! There is an abbey ruin on the site, aptly named Battle Abbey, the altar of which was built on the very spot that Harold Godwineson was killed (as per King William’s instructions). And behind the abbey we found the battlefield, appropriately marked with signboards depicting the stages of the battle.

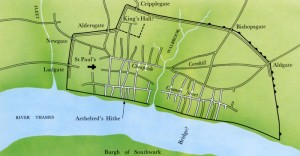

When Duke William landed his fleet on the shores of Britain, he chose the bay of Pevensey, which was a welcoming haven with an old Roman fort, improved by Harold Godwineson and just recently vacated when the Saxon army marched north to Stamfordbridge. However, Pevensey was surrounded by marshland and could not support the army, so William moved his army east to Hastings. There he erected one of his portable (prefabricated) fortifications near the little harbor. Intending to alarm the Saxons as well as live off the land, he laid waste to southeast England. After a couple of weeks he progressed northward toward London, where he was confronted by the exhausted Saxons in their last stand.

When Duke William landed his fleet on the shores of Britain, he chose the bay of Pevensey, which was a welcoming haven with an old Roman fort, improved by Harold Godwineson and just recently vacated when the Saxon army marched north to Stamfordbridge. However, Pevensey was surrounded by marshland and could not support the army, so William moved his army east to Hastings. There he erected one of his portable (prefabricated) fortifications near the little harbor. Intending to alarm the Saxons as well as live off the land, he laid waste to southeast England. After a couple of weeks he progressed northward toward London, where he was confronted by the exhausted Saxons in their last stand.

Why is it called the battle of Hastings? Well, as recently as the 19th century the battle was referred to as the Battle of Senlac; apparently, the venerable historian Edward A. Freeman created quite a controversy by using (or inventing?) this name, which translates to lake of blood. The town of Battle would have been built around the abbey, so it didn’t exist in 1066; Hastings was probably the closest village to the battlefield. Interestingly, no archaeological evidence has been found at the site for any kind of battle, and historians have speculated alternative locations. Even Tony Robbins did a Time Team episode, and concluded that the battle may have been fought right in the middle of the town rather than the traditional field site.