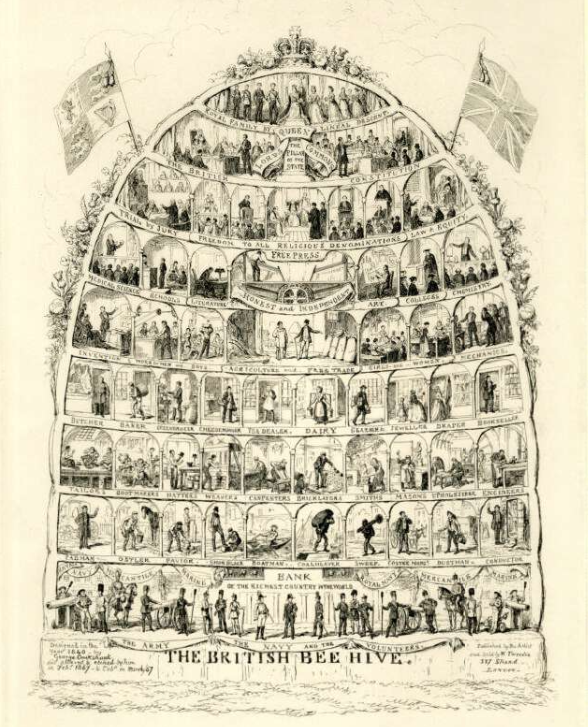

The Second World War was a defining moment in British history, and the impact of the war on the daily lives of those who lived through it was profound. Virtually nothing was the same in 1945 as it had been in 1940. Not only had the British Empire’s place in the world been irreparably damaged, but the social fabric of Britain was starting to tear. Respect for authority had deteriorated, acceptance of the class-system undermined, and the role of women transformed. Furthermore, the material substance of Britain was battered, run-down and partially shattered.

The two most important factors contributing to these changes were: 1) the total mobilization of society necessary to continue the fight, something that entailed near universal conscription (industrial as well as military) and an economy characterized by shortages, and 2) the damage, threat and cost in lives of the air war.

With the wisdom of hindsight, it is easy to dismiss the impact of Hitler’s air war against Britain as paltry. Yet when the Germans opened their assault on London on 7 September 1940 with a raid involving nearly 1,000 aircraft, it represented a scale of aerial warfare no one had previously encountered anywhere in the world.

The all-out assault on London and other urban centers lasted unremittingly for roughly nine months, costing enormous damage, and sporadic conventional air attacks continued throughout the war. Nor was London alone the Luftwaffe’s target. Liverpool was bombed 60 times, Southampton 37, Birmingham 36, Coventry 21 times, while many other cities were bombed lesser numbers of times. Nearly every raid left thousands of casualties and tens of thousands of homes and shops destroyed, scores of factories, dockyards and other installations damaged.

After the Allied landings in Normandy, Britain was subjected to a new terror from the skies when Hitler unleased his “vengeance weapons,” the V1 and the V2. The V1s were essentially drones, while V2s were rockets which fell from 60 to 70 miles high at speeds of 3,600 mph — faster than the speed of sound. They came in too fast to set off air raid warnings or to be intercepted by fighters. The destruction they caused was unprecedented — an entire block or row of houses could be turned into rubble in an instant, while causing collateral damage in a quarter-mile radius.

Altogether, Hitler’s air offensive killed 60,447 people in the British Isles. Of those, 51,509 had fallen victims to conventional bombing, and nearly 9,000 (8,938) to Hitler’s “vengeance” weapons. In London alone, every sixth person had been made homeless during the Blitz which damaged nearly 1.1 million homes. After much had been repaired, the V1s and V2s damaged fully half of the housing in the British capital in 1944/1945.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the British public demanded and expected their government and armed forces to respond. One Air Marshal watching a night attack on London in 1940 was reminded of a phrase from the Old Testament (Hosea 8:7), and predicted: “They have sowed the wind,” he said, “and they will reap the whirlwind.” Truer words were rarely spoken — but the road was long and cost high.

It was not until 1942 that the RAF could launch its first “thousand plane” raid against Germany. The casualty rates among bomber crews were also appalling. Although chances of survival varied over time depending on a number of factors (the type of aircraft, the targets, the timing of attacks, i.e. daylight or nighttime, the availability of fighter escorts, technological innovations in radar and counter-radar etc.), by the end of the war a total of 57,205 aircrew or 46% of all men who flew with Bomber Command had been killed in action. In addition, 8,403 had been invalided and 9,838 taken prisoner. The effective casualty rate was thus 60%. During the height of the bombing offensive, 1943 – 1944, casualty rates hovered around 5% per raid and each crew was required to fly 30 operational flights before they were eligible for a rest.

Yet all the men who flew with the RAF in whatever capacity were volunteers, and only one in ten of the men who served in the RAF during WWII actually flew. In other words, it took nine men on the ground to support (recruit, train, equip, house, feed, and maintain the equipment of) each man who flew. “Aircrew,” the men who flew in whatever capacity (i.e as pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, wireless operators, flight engineers or air gunners), were all viewed as an elite. They were given status and privileges above those of their non-flying comrades and enjoyed gestures of appreciation and admiration from civilians — particularly by the opposite sex.

Winning the coveted “aircrew brevet” was not easy, however. Many candidates “washed out” before qualifying. Pilot, navigator and wireless operator training took as much as two and a half years, and it was dangerous. Over 8,000 men training for Bomber Command alone were killed in training accidents and an additional 4,200 were seriously injured.

Sobering as this must have been for the participants, it had no apparent impact on the willingness of young men to volunteer. The RAF always had more volunteers than they could absorb and to the end could afford to be choosy. (The image below shows one of the many “Wings Parade” at which cadets received the coveted cloth wings symbolizing their qualification as a pilot in the RAF. This particular picture shows the graduation at an airfield in the U.S. Throughout the war, the RAF sent tens of thousands of trainee aircrew overseas for their training — including to the U.S. until the U.S. entered the war the USAAF required all training facilities for itself.)

his wings in the foreground.

And yet! The realities of combat, brushes with death, the loss of friends inevitably took their toll on those on active service. “Shell-shock” and “PTSD” are familiar concepts nowadays. Yet the RAF leadership was shocked when increasing numbers of their carefully selected and meticulously trained volunteer aircrew refused to fly. The refusal to volunteer was hardly a breach of the military code, so the RAF needed another procedure for handling these cases since they otherwise threatened to undermine overall morale.

The term “Lack of Moral Fibre” (LMF) was invented, and any man who refused to fly without a valid medical reason or “lost the confidence of his commanding officer” could be immediately posted off a squadron and subjected to disciplinary measures for “LMF.” During the war itself, it was widely believed that aircrew found LMF were humiliated, demoted, court-martialled, and dishonourably discharged. There were rumours of former aircrew being transferred to the infantry, sent to work in the mines, or forced to do demeaning tasks. Although historical analysis of the records show almost no evidence of widespread humiliation, the rumours of draconian punishment served as a deterrent. Tragically, the threat of public humiliation may also have pushed some men to keep flying when they had already passed their breaking point, leading to errors, accidents, and loss of life. Yet we should not forget that behind the notion of LMF was the deeply embedded belief that courage is the ultimate manly virtue and that a man who lacks courage is inferior to the man who has it.

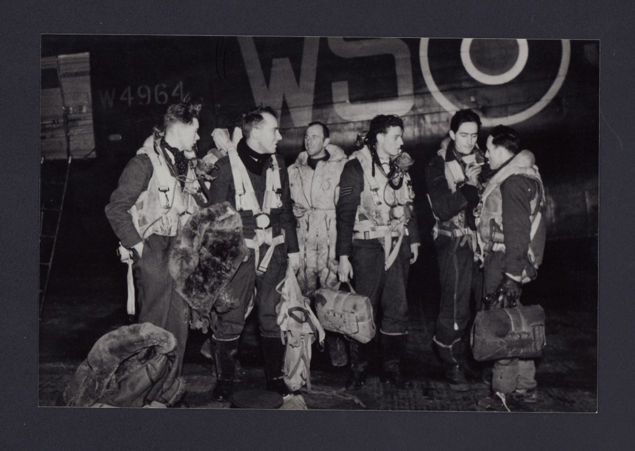

(Below a Lancaster crew immediately following an operation. It belongs to a collection of photographs concerning Sergeant William Frederick Burkitt (1922-1944). Burkitt flew as a flight engineer with No 9 Squadron.)

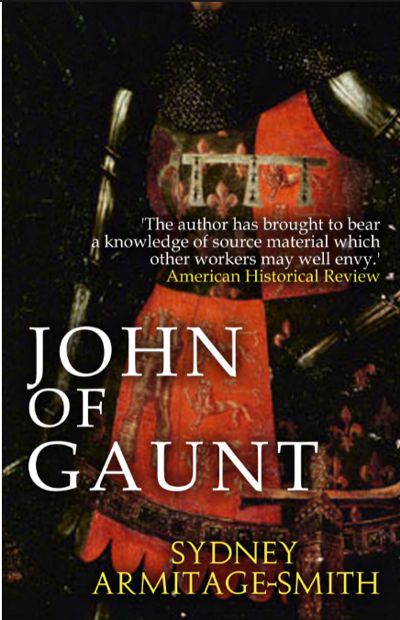

Moral Fibre takes you into the world of the RAF in 1944. While the themes — the many faces of courage, the cost of love, the scars left by grief — are universal and timeless, the book is firmly grounded in the period in which it was set. The hero, Kit Moran, has been posted for LMF in the past, but when the book opens, he is returning to operations. As the pilot of a Lancaster, he is responsible for the lives of six other men — and he is prepared to die for them. Yet his desire for life is kindled by his love for Georgina, a trainee teacher who has already lost her fiancé in the air war against Hitler and is afraid of giving her heart again.

Riding the icy, moonlit sky, they took the war to Hitler. Their chances of survival were less than 50%. Their average age was 21. This is the story of just one Lancaster skipper, his crew and the woman he loved. It is intended as a tribute to them all.

Flying Officer Kit Moran has earned his pilot’s wings, but the greatest challenges still lie ahead: crewing up and returning to operations. Things aren’t made easier by the fact that while still a flight engineer, he was posted LMF (Lacking in Moral Fibre) for refusing to fly after a raid on Berlin that killed his best friend and skipper. Nor does it help that he is in love with his dead friend’s fiance, who is not yet ready to become romantically involved again.

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/Moral-Fibre-Bomber-Pilots-Story-ebook/dp/B09XWMNWRX

Amazon UK: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Moral-Fibre-Bomber-Pilots-Story-ebook/dp/B09XWMNWRX

Barnes & Noble: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/moral-fibre-dr-helena-schrader-phd/1141389873?ean=9781735313924

Itasca Books: https://itascabooks.com/products/moral-fibre-a-bomber-pilots-story

Meet Helena P. Schrader

Helena P. Schrader is an established aviation author and expert on the Second World War. She earned a PhD in History (cum Laude) from the University of Hamburg with a ground-breaking dissertation on a leading member of the German Resistance to Hitler, which received widespread praise on publication in Germany. Her non-fiction publications include Sisters in Arms: The Women who Flew in WWII, The Blockade Breakers: The Berlin Airlift, and Codename Valkyrie: General Friederich Olbricht and the Plot against Hitler, an English-language adaptation of her dissertation. Helena has published nineteen historical novels and won numerous literary awards, including “Best Biography 2017” from Book Excellence Awards and “Best Historical Fiction 2020” from Feathered Quill Book Awards. For more on her publications, works-in-progress, reviews and awards visit: http://helenapschrader.com

Or visit me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/helena.p.schrader.7