In the days of Edmund Ironside, the name Eadric Streona keeps popping up at the most critical moments… and not in a happy way. It seems that this slippery Mercian Earl must have had incredible powers of persuasion, because he kept turning up no matter how often he changed sides. No one seemed to know whether he was working as a spy for Canute or as an advisor to Edmund, and no one seemed to understand why the Saxon King could trust him. Where did this man come from?

Streona was not the last name of Eadric of Mercia; rather, it was a nickname which roughly translates to “the Acquisitor”. He became Earl of Mercia in 1007, apparently as a result of murder, or rather, doing King Aethelred’s dirty work while acquiring the lands of tax defaulters. He married the king’s daughter Eadgyth in 1009, which made him brother-in-law to Edmund Ironside.

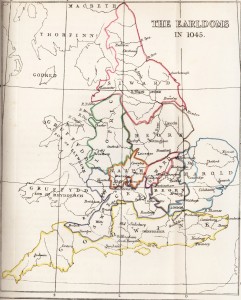

In 1015, Eadric procured the murder of Siferth and Morcar, two leading thegns in the Danelaw. We can assume that he did this for Aethelred, since the King benefited from confiscating their estates; he also ordered the arrest of Siferth’s widow. Following this episode, Edmund (not yet Ironside), in defiance of his father, carried off the widow and made her his wife. So Edmund became lord of the so-called Five Boroughs in the East Midlands, while Canute was hostile to the Danelaw at the time. At first, Eadric helped Edmund raise troops to fight Canute, but since Edmund had just married the widow of the thegn Eadric had murdered, Streona was soon plotting to betray him. Within four months after Canute’s arrival in England, Eadric had sworn homage to the Danish chief along with forty Mercian ships.

In 1016, Aethelred the Unready died and Edmund the Aetheling was immediately elected King by the citizens of London. Unfortunately for him, Canute was elected King by the Witan in Southampton, thus causing a dilemma that wreaked havoc for the next seven months. London bravely withstood three sieges by Canute, and King Edmund did his best to draw the Danes away from the city. Eadric was present at every major battle, first on one side then the other.

His first infamy was at the Battle of Sherstone, fought on the border of Wessex and Mercia. Eadric sided with Canute, and on the second day he smote off the head of a warrior who looked like Edmund Ironside and held it up to the King’s army, shouting that the King was slain. The English wavered, about to take flight when Edmund tore off his own helmet, exclaimed that he lived and threw a spear at the traitor. Unfortunately, the spear missed Eadric and skewered someone next to him. The King’s army rallied but the day ended in a draw.

The Danes went back to their ships, but Eadric returned to his brother-in-law and swore fealty to him. No one knows why, but Edmund took the Mercian Earl back into his favor. The King levied a new army and closely pressed the Danes who were on the run, but Eadric was said to have contrived to detain Edmund long enough for the Danes to recover. Then, at the battle of Assandun, in charge of his own troops, Eadric suddenly turned tail and fled from the field, causing great slaughter.

For some reason, Eadric was still in King Edmund’s confidence, and after the defeat of Assandun managed to persuade the King to meet Canute in person. The two kings met on an island in the Severn and ultimately agreed to divide England between them, with the understanding that each King was the other’s heir. Poor Edmund did not survive the year; although no accusation of foul play was agreed upon by chroniclers, it was thought by many that Eadric quietly did away with Edmund Ironside. A nasty rumor survived that Eadric climbed into the King’s garderobe and skewered him from below, though I suspect that was vicious rumor.

From Canute’s point of view, Eadric Streona, had outlived his usefulness. Although he had retained his Earldom of Mercia, Eadric is said to have expected more rewards and upbraided Canute for his lack of appreciation. Some went so far as to state that Eadric claimed he killed Edmund for Canute, but again I suspect this is poetic license. Regardless, it is certain that Canute had him killed at the Christmas Gemot. My favorite story is that he had Earl Eric cut off his head and throw it out the window into the Thames. How very appropriate!