When we study the succession of post-conquest English kings, we often forget that England might not be their primary interest. This may be the reason that William the Conqueror groomed his eldest son to inherit the Dukedom of Normandy and gave the English crown to a younger brother. Or was it because Robert, surnamed Curthose was a bit of a wastrel and couldn’t be depended on to manage his tempestuous new conquest?

Robert does not present a very appealing picture. He is described as short and fat with a heavy face, but at the same time it is said he was a powerful warrior, generous and bold and likeable. However, as in the case of Henry II and his eldest son Henry the Young King, poor Robert was given Normandy as his inheritance, but not allowed to rule or even receive any revenue with which to pay his followers. Nor did William share any of the spoils of his new kingdom of England with his eldest son. William expected him to be content with an empty title and bide his time until William was ready to die.

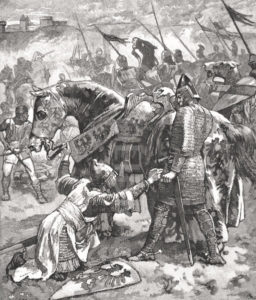

Robert had other ideas and bitterly reproached his father, to no avail. Finally, frustrated, impoverished, he surrounded himself with his friends who were also sons of nobles and wandered hither and yon; he invoked aid from William’s tempestuous underlords and waged rebellion against his father. There is no doubt that he was also helped by the King of France, who was always ready to wreak havoc with William. Finally, the French King permitted Robert to occupy the castle of Gerberol on the borders of Normandy and France, and William had to take a firm stand against his errant son. Laying siege to the castle in 1079, William received his first ever wound, unluckily by the hand of his own son. At the same moment, an arrow killed William’s horse and he fell to the ground, expecting to receive the final death blow; lucky for him William was saved by a loyal Englishman who gave up his own life. In the fighting that followed, even William Rufus was wounded defending his father, and the Conqueror retreated, leaving the victory to his rebellious son.

Humiliated, William retreated to Rouen and the rebellious Robert, perhaps in remorse, took his followers and passed over to Flanders. Although William was incensed, he listened to the arguments of the nobles in Normandy, many of whom were fathers of Robert’s companions. They urged him to reconcile and he eventually agreed, receiving his son and friends and renewing the succession, as before.

When William the Conqueror died in 1087, Robert and William II made an agreement to be each other’s heir, but this arrangement was short-lived and the wily Norman barons sought to get rid of the stronger brother (the King of England) in favor of the weaker brother they thought they could control. In the following year, the rebel Barons fortified their castles in England. Led by William the Conqueror’s elder half-brothers Odo of Bayeux and Robert Count of Mortain, they marched against William Rufus in the expectation that Robert would bring supporters from Normandy and join their forces. Alas for them, bad weather forced Robert back across the channel and the rebellion collapsed.

In 1096, Robert went on Crusade, not to return until five years later – too late to stop his younger brother Henry from taking the crown of England on the death of William II. He led an invasion that came to nothing, and eventually annoyed Henry so much that the new King of England invaded Normandy instead, capturing Robert in 1106 and imprisoning him for the rest of his life. Robert lived in captivity another 28 years and died in his early 80s.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

I suspect that the bad weather was not the only factor: Alan Rufus was in charge of the City and Port of London as well as many other ports in England. It’s likely that the English navy was manned by Alan’s redoubtable Breton sailors.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

The sources from the English side say that the ships of Robert’s advance fleet that were not captured were sunk by the English fleet. So there you have it.

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Could be…how large was the English fleet at this time?

Geoffrey Tobin says:

An excellent question. Can we find out how many ships the English navy had in 1088?

That fleets of some 200 ships from Denmark on several occasions during William I’s reign turned tail and fled might suggest that from 1068 onwards England’s fleet was larger than 200 ships. Perhaps this is a lower bound on the size of the fleet based at each major port – if that’s how the defence was organised.

There’s a discussion of Anglo-Saxon era navies in “Anglo-Norman Studies XIX: Proceedings of the Battle Conference, 1996

edited by Christopher Harper-Bill”. Page 374 mentions evidence that Harold had sent ships to intercept William’s invasion force.

According to the entry for 1088 in “The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain 660-1649”, by N.A.M. Rodger, Robert of Mortain’s port at Pevensey was blockaded by a fleet in 1088, bottling him and Odo in and preventing the arrival of any relief force from Normandy.

William M. Aird in his book on Robert ‘Curthose’ mentions Robert seeking to employ pirates to harass English shipping and thus distract the English fleet so that his naval expeditionary force could reach shore unhindered. Nonetheless, it was intercepted at sea.

So it seems William II’s southern fleet was strong enough to blockade Pevensey, deal with pirates and sink the vanguard of the Norman navy all at the same time.

I speculate that the English naval crews of 1088 comprised Englishmen, Bretons and Normans who were loyal to the King, and thus helped lead to an increasing sense of common cause among the disparate ethnic groups of post-Conquest England, and that its success against Normandy and the rebels contributed to the country’s dawning realisation of its potential as a naval power.