Medieval York is the setting for my new novel, Rogue Knight. Today it is a prominent city in Yorkshire in the North of England. And it was before the Conquest.

Though it has ancient origins, the city was founded by the Romans in 71AD. At one time, there was an old Roman fortress where the Minster is today. When Britain converted to Christianity in the middle of the second century, York became the seat of the archbishopric.

In the seventh century, York was the main city of the Northumbrian King Edwin, but in 866, the Danes captured York and it became the capital of the Danelaw where the laws of the Danes governed from the 9th into the 11th century. The growth in York’s size and prosperity beginning with the 10th century was accompanied by a transformation of the countryside with well-planned villages surrounded by arable open fields. Until the eleventh century, there were virtually no towns in Yorkshire except York. And York was the only town with a mint north of the Humber River until after 1066.

Sweyn of Denmark conquered England in 1013 and was succeeded by his son Cnut the Great who ruled as King of Denmark, England and Norway. He and his progeny effectively ruled England until Edward the Confessor.

While the term “Yorkshire” was not recorded until about 1050, it is thought to have been created around 1000. By at least 1033, King Cnut had appointed Siward as Earl of Northumbria, including a greater Yorkshire, south Lancashire and (from 1041), Durham and Northumberland. In its language and culture, York was Anglo-Scandinavian. Even at the time of the Conquest, almost every street in the city of York had the Old Norse suffix “gata” or “gate” meaning “street” and most of the personal names of the people would have been Scandinavian. Likely Old Norse was spoken in the city, too. (It is in my novel.)

Excavations of the Coppergate area have revealed that York was importing a wide range of goods: Rhenish pottery (probably originally containing wine), honestones (for sharpening) from Scandinavia, clothing pins from Ireland, amber from the Baltic and cowrie shells from the Red Sea or Gulf of Aden. And there was silk, too, probably from Constantinople or Asia. They have even found Islamic coins from Samarkand. It was a city of business and trade. More 10th and 11th century weights and balances have been found in York than anywhere else in England.

In 1055, Siward died leaving one son, Waltheof (a character in Rogue Knight). Waltheof would later have a rather amazing life, first as an English earl, then as a rebel in Northumbria in 1069, but when his father died, Waltheof was too young to succeed as Earl of Northumbria, so King Edward appointed Tostig Godwinson to the earldom. And we all know where that led.

In 1066, Harald Hardrada obtained the submission of York after the battle of Fulford Gate. Not only did York provide Hardrada with supplies, they agreed to support him in his conquest of the south. It has been suggested that York was a willing accomplice in Harald’s venture; he might have been preferable to the distrusted Harold Godwinson. An exchange of hostages was arranged, and Hardrada moved on to Stamford Bridge to await their arrival. But it was not meant to be; after a forced march, Harold Godwinson passed through York on his way to Stamford Bridge and forestalled any further commication with the Norwegian King.

Both Tostig and Harald died at the Battle of Stamford Bridge and soon thereafter Harold of Wessex fell to William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings. At the time, York was the largest city north of London and an important center of commerce with as many as 15,000 residents, thus it was a city William the Conqueror very much wanted under his control. However, it was not to come to him easily. The people of York did not consider William their king any more than they had the Saxon Harold Godwinson before him. The years following the Conquest would see uprisings in York, one in 1069, led by the Danes with 240 ships. And that story is told in Rogue Knight.

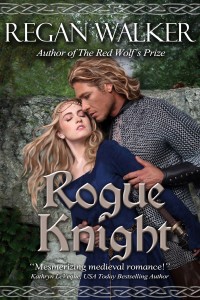

Rogue Knight by Regan Walker

York, England 1069… three years after the Norman Conquest

The North of England seethes with discontent under the heavy hand of William the Conqueror, who unleashes his fury on the rebels who dare to defy him. Amid the ensuing devastation, love blooms in the heart of a gallant Norman knight for a Yorkshire widow.

A LOVE NEITHER CAN DENY, A PASSION NEITHER CAN RESIST

Angry at the cruelty she has witnessed at the Normans’ hands, Emma of York is torn between her loyalty to her noble Danish father, a leader of the rebels, and her growing passion for an honorable French knight.

Loyal to King William, Sir Geoffroi de Tournai has no idea Emma hides a secret that could mean death for him and his fellow knights.

WAR DREW THEM TOGETHER, WAR WOULD TEAR THEM APART

War erupts, tearing asunder the tentative love growing between them, leaving each the enemy of the other. Will Sir Geoffroi, convinced Emma has betrayed him, defy his king to save her?

Links:

Rogue Knight on Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/Rogue-Knight-Medieval-Warriors-Book-ebook/dp/B014ZCMWZ4

Author website: http://www.reganwalkerauthor.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/regan.walker.104

Pinterest storyboard for Rogue Knight: https://www.pinterest.com/reganwalker123/rogue-knight-by-regan-walker/

Regan Walker says:

Greetings, Mercedes. And thanks so much for having me on your wonderful blog. I’m delighted to be here sharing bits from my research for Rogue Knight.

Regan

ReganWalkerAuthor.com

Geoffrey Tobin says:

William I’s proclamations were written in Latin and English. In the North the texts are written in what looks to me like the Anglo-Saxon of Beowulf, so it’s reasonable to suppose that this is what the people there spoke.

In the South the vernacular used in these official documents was very like Modern English, apart from changes in spelling and the absence of French vocabulary. I find these texts easier to read than Chaucer’s dialect!

So it would seem that Scandinavian immigrants kept or renewed the old North Sea tongue in the Danelaw, whereas something drastic had happened to Anglo-Saxon in the south long before 1066. Maybe the British couldn’t stomach Saxon grammar?

A recent study on ancient autosomal DNA in four early Anglo-Saxon graves in Cambridgeshire (including Linton, where some of my family used to live) has shown that the wealthiest grave was that of a Celtic man, whereas the poorest grave was a Saxon’s, and the other two were of mixed descent. The form of burial was much the same, apart from the grave goods. It seems that in this sample, the Saxon was a servant who adopted British customs: the opposite to the conventional account. Moreover, the two ethnic groups evidently intermarried peaceably.

The same researchers estimated that English DNA was 38% Saxon. Surprisingly they got a figure of 30% Saxon for Welsh DNA. Did the Saxons become servants in Wales, too? Or does “Saxon” autosomal DNA not necessarily imply first millennium immigration from Saxony?

A study (see http://www.surnamedna.com/?articles=y-dna-of-the-british-monarchy) has been made on the Y DNA of the Danish royal house, the Oldenburgs, of which Prince Philip is a member as were the Romanovs. The Oldenburgs originate in Lower Saxony. They have R1b, like most of the Atlantic coastal Europeans (including British and Basques). More precisely, they are in the “Atlantic Modal Haplotype cluster”. Samples have only 17 “STR” values which is not enough to distinguish L21 (a Celtic variety) from U106 (Saxon).

The main point is, they’re not Norse (I1).

Regan Walker says:

Geoffrey, I doubt you have read my novel, or you would know most of what you say is irrelevant. None of it takes place in Wessex or the south of England. If you mean to say the people living in York in 1069 were not still highly influenced by the Danish culture, in names, dress, customs and dialect, I respectfully suggest you are wrong. I did hundreds of hours of research to get it right. The DNA study you cite does not alter my thinking in the least. Also, no matter his proclamations, William soon gave up speaking English and reverted to French, speaking French to his knights. He cared nothing for the Saxons or the rest of the English. His goal was absolute conquest, all the land for himself and his Norman friends.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

Regan, I referred to the spoken language in the North in that period being close to early Anglo-Saxon. Indeed I was contrasting North with South, giving documentary evidence of how different the Danelaw was from Wessex. Clearly by 1070 they spoke mutually unintelligible languages.

The archaeological findings are too new and too few to extrapolate from, but one might be justified in thinking that many regional differences have early origins. The Norse settlement apparently reinforced those differences.

I have seafaring Chapman ancestors who as best I can tell came from Whitby, then spent a good century in Sweden. The family may have been among the first Angles to settle in Yorkshire. So I’m conscious of the trade and cultural links across the North Sea and Baltic countries. (Look for Chapman Bank and Fredrik Henrik af Chapman, if you are interested.)

I hope you can see that I am not challenging your research: quite the opposite.

Regan Walker says:

Ah, I do see. Well, it’s nice to have such deep and illustrious ancestral ties. As I was researching and writing Rogue Knight I felt the loss of such a place when the Normans burned it nearly to the ground, even York Minster. It was a culturally rich place with thriving people most of whom ended up killed or starved. William I was not a nice man. I wonder how many of your ancestors survived the Harrying of the North, the story of which is told in my novel as close to the facts as I could present it.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

Postscript: Regan, I observe that your novels are based on real persons, more so than say Bernard Cornwell’s.

Geoffey de Tournai was one of Count Alan’s men and PASE Domesday records that he held property in “Stenning in Swineshead” in Lincolnshire, an estate previously held by Healfdene.

Open Domesday gives more information about the land, but spells it Steyning. It was in the Hundred of Kirton in the Area of Holland. It paid King William 3 geld and 0.4 salt-house’s worth of salt from its 6 salt houses. There were 8 households in the village, paying Geoffrey a total of one pound per year in rent. That’s an average of 30 pence per household. There were 3 plough lands. 2 plough teams worked for Geoffrey, and half a team for “his men”. There were 50 acres of meadow.

Healfdene’s name is Old English for Half-Dane. This might be a literal description of his parentage, or he might have been named after a King of the Danes mentioned in “Beowulf”. In any case, he owned 18 properties in 6 hundreds in Lincolnshire before the Conquest, none after. His father’s name was Topi, so perhaps he was related to “Topi father of Ulf”, one of Earl Morcar’s men, as this Topi owned some land in Kirmington, in the Hundred of Yarborough, near where Healfdene owned several properties.

Regan Walker says:

Geoffrey, you’d have to read my medieval stories to see how I do it. Yes, I use real historic characters when I can and blend them with my fictional characters, not unlike Cornwall does. All of the knights’ names I used were men whose names are on the list of those who accompanied William the Conqueror in 1066 and passed through Dives-sur-Mer. But Geoffroi de Tournai in my novels is a FICTIONAL character. The lands William gives him will be in the Northwest where the fictional holding of Talisand (first seen in The Red Wolf’s Prize) is located. I hope this helps.