It goes without saying that any usurper will have to deal with resistance. Considering the wave of popularity that thrust Henry Bolingbroke onto the throne, I imagine he never would have suspected the number of rebellions he would have to confront in the first five years of his reign. Some were major, others were minor. Two nearly condemned him as the shortest reigning monarch in English history. All must have been disheartening to the man who saw himself as an honorable, chivalric knight.

What could possibly have gone wrong?

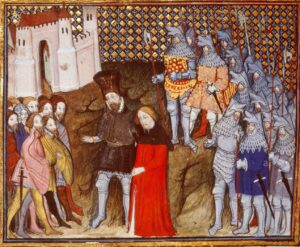

The first rebellion wasn’t much of a surprise—though the timing was shocking. Only three months after his coronation, King Richard II’s favorites launched the Epiphany Rising of January, 1400. Their aim was to capture and kill the king and his family on the eve of a tournament at Windsor Castle. Unfortunately, they were in too much of a hurry; Henry was still at the height of his popularity. At the very last minute, King Henry was warned and he made a frantic escape to London. Nonetheless, the ringleaders were committed; after they found their prey had flown they continued with their revolt, though they weren’t able to attract as much support as they expected. Rather, most of them suffered the indignity of being killed by the citizenry, who took the law into their own hands.

Needless to say, the Epiphany Revolt put an end to Richard. Or did it? Although he was reported dead by February 14 and a very public funeral was held, rumors spread that he had escaped to Scotland and was going to return at the head of an army. Disgruntled rebels were quick to challenge the usurper in his name, and the spectre of a vengeful Richard haunted Henry for the rest of his life. Or, if Richard was dead, the young Earl of March—considered by many the true heir to the throne—served the same purpose. As far as the rebels were concerned, one figurehead was as good as the other.

During most of Henry’s reign, the country was bankrupt—or nearly so—and the first few years were the worst. It didn’t take long for the populace to cry foul, for as they remembered it, he promised not to raise taxes (untrue). Things were supposed to get better (they didn’t). Mob violence was everywhere. Even tax collectors were killed. Meanwhile, a fresh source of rebellion reared its head: the Welsh.

On his way back to London after his first (and only) campaign into Scotland, the king learned of a Welsh rising led by one Owain Glyndwr, who visited fire and destruction on his recalcitrant neighbor Reginald Grey of Ruthin. Turning immediately to the west, Henry led his army into Wales, chasing the elusive enemy deep into the mountains. Unfortunately, lack of funds and terrible weather forced them to turn back. But this just added fuel to the proverbial fire. Repeated Welsh raids unsettled his border barons, who were quick to complain. During parliament—only one year after Henry’s coronation—the Commons insisted on enforcing the most repressive anti-Welsh legislation since Edward I. None of these laws would have been enacted in Richard’s reign. The Welsh were in no mood to acquiesce, and their rebellion gained steam for the next several years, sapping an already exhausted exchequer.

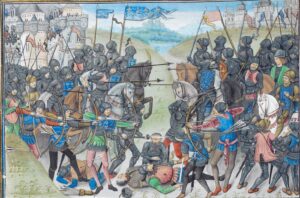

Then there were the Percies. The Earl of Northumberland and his son, Harry Hotspur were instrumental in putting Henry on the throne. They also ruled the north as though it was their own kingdom. This would not do, and Henry followed his predecessor’s strategy of raising up other great families as a counter to their ambitions. Disappointed that Henry did not appreciate them as much as they expected—especially after they won Homildon Hill, the most significant battle against the Scots since Edward I days—the Percies launched a totally unexpected assault in 1403. It was Harry Hotspur who drove this insurrection, using Richard II’s imminent return as a means to raise the restive Cheshiremen to his cause. Once his soldiers realized that Richard wasn’t coming, they fought to avenge him instead. The resulting Battle of Shrewsbury was a very close call; if Henry hadn’t unexpectedly traveled north from London that week to join Henry Percy, he never would have been close enough to intercept the rebels when he learned about the uprising. The fighting was ferocious; it was only Hotspur’s death on the battlefield that determined which side had won the day. As it was, Percy’s ally, the Earl of Douglas, allegedly killed two knights who wore Henry’s livery, giving their lives to save the king in the confusion of battle.

The Earl of Northumberland was still in the North when the Battle of Shrewsbury took place. Historians can’t decide whether Percy’s failure to assist his son was planned or unplanned. But one thing was for sure; Henry Percy was still a force to be reckoned with. Although the king reluctantly pardoned him (with the urging of the Commons), he was back two years later, leading another rebellion in conjunction with a rising led by Richard Scrope, the Archbishop of York, and Thomas Mowbray, son of Henry Bolingbroke’s old rival. Northumberland’s thrust was repelled before he gained much speed, yet Scrope’s forces waited at York for three days before being tricked into disbanding by the Earl of Westmorland, Percy’s nemesis. Poor Archbishop Scrope became the focus of King Henry’s rage. Despite resistance from all sides, the king ordered him to be executed, creating a huge scandal and a new martyr.

Henry Percy suffered outlawry at that point, but he returned three years later, fighting one last battle, so pathetic one wonders whether he had a death wish. He was killed on the field and subsequently decapitated.

These were the major rebellions. Other disturbances were usually dealt with without Henry’s presence. In 1404, Maud de Ufford, Countess of Oxford—mother of the ill-fated Robert de Vere, Richard’s favorite—organized an uprising centered around the return of King Richard. This was in conjunction with Louis d’Orleans, the French duke who planned to invade the country in December. Alas, he was held up by the weather and Richard failed to materialize. In 1405, Constance of York, sister of Edward (Rutland), Duke of York concocted a plot to kidnap the young Earl of March (remember him, the other heir to the throne?) and his brother from Windsor Castle. She was taking them to Owain Glyndwr but got caught before they entered Wales. She implicated her brother who was imprisoned for several months, but no one knows for sure whether he was complicit or not (he probably was).

Bad weather, failed crops, an empty exchequer, regional disorders, piracy that disrupted the wool trade, all contributed to general unrest that plagued the fragile Lancastrian dynasty. Henry’s willingness to accept criticism from friends and supporters—and sincerely try to act upon it—could well be one of the reasons he survived and King Richard failed.