Like many of us, I first learned of Richard II from Shakespeare. Even though I knew nothing about him, I was totally moved during the prison scene while he bemoaned the fate of kings—and I never recovered! But his story goes way beyond the events of this play; in fact, Shakespeare only covered the last year of Richard’s life. He tells us nothing about what led up to the famous scene between Bolingbroke and Mowbray, where their trial by combat was interrupted and they were sent into exile. This was indeed the crisis that led to the king’s downfall, but Richard’s story is much more complicated than you would ever think from watching the play.

First of all, did you realize that Henry of Bolingbroke was Richard’s first cousin? The clues are all there but it’s not easy to put them together. The old John of Gaunt (“This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England…”) was the eldest of Richard’s surviving uncles, and because Richard was childless he was next in line to the throne (debatable, but that’s another story). Bolingbroke, Gaunt’s eldest son, was next after him. This did not appeal to Richard; in fact, according to all reports, having Bolingbroke as his heir was anathema. Why? Events in my book, A KING UNDER SIEGE, will give you a good idea. Richard and Henry were never friendly, but during the second crisis in Richard’s reign, Bolingbroke was one of the Lords Appellant—the five barons who drove the Merciless Parliament to murder the king’s loyal followers.

Richard’s minority was not easy. The doddering Edward III was hardly a role model, and neither was his father, the ailing Black Prince who languished for years, disabled and debilitated. On Edward III’s death, Parliament insisted on Richard’s coronation instead of a regency; many feared that John of Gaunt would seize the throne. Nonetheless, what could one expect from a ten year-old? Four years later, the boy king proved himself worthy during the Peasants’ Revolt, but his subsequent attempts to assert himself led to conflict with his magnates. His bad temper, sharp tongue, and impetuous nature gave the restive barons plenty of excuses to hold him down. Richard’s solution was to surround himself with cooperative friends and advisors and exclude the self-righteous lords from his inner circle, which infuriated them. The king needed proper guidance, they insisted; his household needed purging.

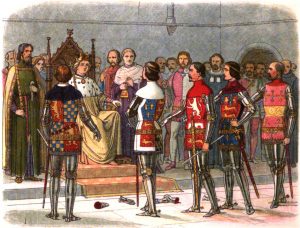

The Lords Appellant, as they came to be known, threatened Richard with abdication—humiliating him and destroying his power base. At first there were three of them: Richard’s uncle Thomas Duke of Gloucester, Thomas Beauchamp Earl of Warwick, and Richard FitzAlan Earl of Arundel. After Richard’s aborted attempt to raise an army in defense, Henry of Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray joined their ranks—the same who challenged each other in Shakespeare’s play.

So you can see that Shakespeare’s trial by combat had a lot more going on than could easily be explained. Richard may have appeared detached while he observed the quarrel between Bolingbroke and Mowbray, but under his regal bearing he must have been shivering with glee. The altercation between these two knights was actually the result of their involvement in the Merciless Parliament. A year before the play took place, Richard had already succeeded in wreaking revenge on the original three Appellants. Mowbray feared that their turn was next, and when he voiced his concerns to Bolingbroke, the latter tried to save his skin by telling the king. The argument escalated from there, giving Richard the perfect opportunity to get rid of both of them. He made his fatal error when he went too far and deprived Bolingbroke of his inheritance.

Shakespeare gave us the poignancy of Richard’s last days. Historians have left us more of a conundrum which may never be sorted out. Richard’s 22-year reign can be divided into two parts: the 12 years of his minority and the ten years of his majority—each of which are brought to a tragic climax. Hence, it will take two books to cover his story. As you might guess, volume two will be called THE KING’S RETRIBUTION.