While working on my novel FATAL RIVALRY, I had quite a struggle putting together a timeline for events leading up to Stamford Bridge. Many histories (even Wikipedia) tell us that as soon as Harold learned of the defeat at Fulford, he rushed north and surprised the Vikings who expected him to be at the other end of the country. OK, I understand the surprise part. But really, Fulford was fought on September 20 and Stamford Bridge was fought on Sept. 25. Even if Harold and his mounted army were able to do 50 miles a day (unlikely, though I suppose not impossible), this would be predicated on having an army standing by, ready to go. Oh, and how about hearing the news in the first place? Someone had to travel the 190 miles or so from Fulford to London so Harold could get the message. Already that doubles the time he would have required, and what are the odds a messenger would push himself to do 50 miles per day?

There’s little doubt Harold would have set out shortly after he heard the alarming news. Presumably he would have started the march with his housecarls, who were the closest to a standing army available—it has been suggested he had 3000 at hand. He is said to have gathered forces as he rode north, which again must have taken time for they had to be notified and given a chance to prepare themselves—then travel a distance to meet Harold on the march. We don’t know how big the English army was—somewhere between 8,000-15,000 men—but this is one big logistical task in an age when communication was slow and unreliable. Yes, Harold’s march to York was certainly noteworthy, but I don’t think he was a miracle worker! (Even historian Edward A. Freeman was not prepared to accept the five day forced-march saga.)

Cooler heads have sorted out a more reasonable scenario. Harald Hardrada met his first major resistance in Northumbria at Scarborough, which would have been probably the first week of September. Presumably someone would have ridden south at that point, to notify the king of the Viking raids. Meanwhile, we know Harold disbanded the fyrd on September 8 according to the A.S. Chronicle, because “the men’s provisions had run out, and no one could keep them there (on the south coast) any longer”. The timing would be such that Harold could have received the news about Hardrada shortly after he returned to London. He certainly needed some time to prepare for a new campaign and wait for his mounted thegns to come back. So it stands to reason that he might have started his march north some time between Sept. 12-16, which would have given him 9-13 days to reach Stamford Bridge. Undoubtedly he learned about Fulford along the way, which would have spurred him on to greater efforts.

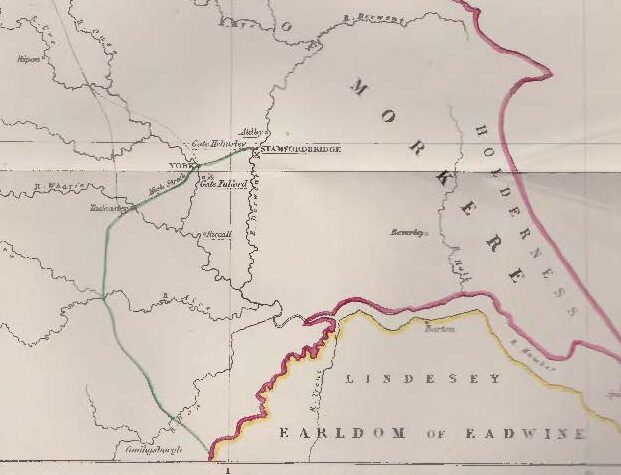

On September 24, four days after the Battle at Fulford, Harold arrived at Tadcaster with his exhausted troops. This town was upriver from Riccall where Hardrada had spread out his 300 ships (beyond a fork where the Wharfe meets the Ouse). It is believed that the Northumbrians withdrew their little fleet to Tadcaster when the Norwegians approached, since they were no match for the invaders. Harold spent the night at Tadcaster and started early in the morning to York, approximately ten miles away. By now he probably learned of Hardrada’s arrangement to wait for hostages at Stamford Bridge. It goes far to suggest that the northerners accepted Harold as their rightful king, for no one sought to warn the Norwegians of the royal army’s approach.

York may have surrendered to Hardrada, but it was apparently lightly guarded by the Norwegians—if at all. Harold made an unhindered entry into the city, acclaimed by the grateful inhabitants who must have felt doubly relieved that they had not been plundered. He marched his army through York and continued east another eight miles to Stamford Bridge. This means his army covered 18 miles that day before engaging the enemy. No rest for the weary!

David says:

The big what if is had William arrived first and been defeated would Harold have sorted the Danes ?

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Such a good question! My thought is that without the element of surprise, the Danes would have been much, much harder to beat

David says:

Without the invasion in the North Harold would have defeated William ?

Geoffrey Tobin says:

I imagine the mounted troops changed horses regularly along the route.

The messages may have been transmitted by pony express (Alexander the Great used such a mail service to convey letters from his army to their families at home).

It’s conceivable that some sort of semaphore system was employed – think of the Native American smoke signals, or the beacons of Gondor.

During the fighting at Fulford, Harald Hardrada’s Norwegians (not Danes) received reinforcements from their ship guards. This prolonged the battle and probably cost the English army dearly. Had the entire Norwegian force been armed, armoured and gathered at Stamford Bridge, it’s anyone’s guess who would have won.

Fulford Gate and Stamford Bridge must have been very costly to Edwin and Morcar. I don’t blame them for not joining the Godwinsons at Hastings, as it’s doubtful they had enough living, let alone unmaimed, men to make a difference.

Incidentally, King William leased out Fulford Gate to Alan Rufus. Their kinswoman Judith of Flanders (named after her grandmother Judith of Brittany) was Tostig’s widow; she subsequently married Welf I of Bavaria.