Earl Waltheof’s foray into the history books was unlucky and unhappy. From beginning to end, it seems like he was in the wrong place at the wrong time and never managed to live up to his destiny.

Waltheof was the younger son of Earl Siward, who died when Waltheof was only 10 years old. His older brother Osbeorn was killed in the battle of Dunsinane, and his father died the following year. Because of his extreme youth, the earldom was given instead to Tostig Godwineson, and it is possible that Waltheof received a monastic education in the interim. It wasn’t until the Northumbrian revolt of 1065 that Waltheof was granted the southern part of the earldom, or Middle Anglia, and he was given the title Earl of Huntingdon.

By all indications, Waltheof was not involved in the Battle of Hastings since he retained his earldom after 1066. He may have briefly served as a hostage for William the Conqueror; perhaps this is where he met Eadgar Aetheling and chose to champion his cause in the last of four Northumbrian uprisings in 1069. By then, Eadgar had fled to Malcolm III’s court in Scotland, and together Eadgar, Waltheof and a party of disgruntled thanes met with an invading force of Danes and destroyed the Norman garrison in York. Waltheof’s exploits in beheading the fleeing Normans with his great axe have been recorded alongside his warlike ancestors.

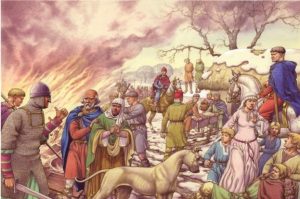

Alas, the raiding party could not organize a defence against the wrathful King William, who Harried the North in a devastating scorched earth reprisal that scattered his enemies and forced Waltheof to submit to his mercy. For the moment, Luck was with the earl, for William gave him a second chance and even married him to his own niece Judith (though perhaps Waltheof’s Norman wife was placed to keep an eye on him). After two years Waltheof was made the first earl of Northumberland (not to be confused with Northumbria which was much larger) and reigned from 1072-1075.

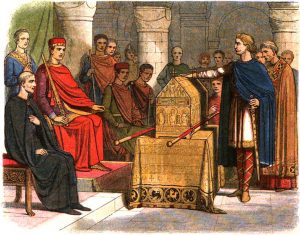

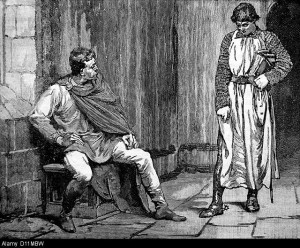

Unfortunately, Waltheof managed to get himself involved with an ill-fated Revolt of the Earls, thought better of it and rushed to confess his role to William. The Norman King seemed to forgive him in face of his timely confession, and William finished off the other Earls and made short work of the revolt. However, an untimely appearance of another Danish fleet in the Humber must have given William pause, and he kept Waltheof in close confinement. Alas for Waltheof, his wife Judith publicly accused him of complicity and after several months he was declared a traitor and sentenced to be beheaded.

The last Saxon earl was executed May 31, 1076 on St. Giles Hill, Winchester. In an excess of piety and atonement, Waltheof threw himself on his knees and burst into prayer. It was said that the executioner got tired of waiting for him to finish and struck off his head while in the midst of the last sentence. Witnesses swear that his severed head finished with “but deliver us from evil. Amen” clearly and distinctly. It wasn’t long before the unhappy Saxons started to treat him like a Saint.

But all did not end with Waltheof’s execution. He was survived by a daughter Matilda, who eventually married David, King of Scotland and son of Malcolm III. From this marriage came the Earls of Huntingdon, as well as her grandsons, Malcolm IV and William I of Scotland.

As for William the Conqueror, it is said that his good fortune ended with the wrongful execution of Earl Waltheof. From then on, William conquered no more, and the last decade of his life proved to be unhappy and fruitless.