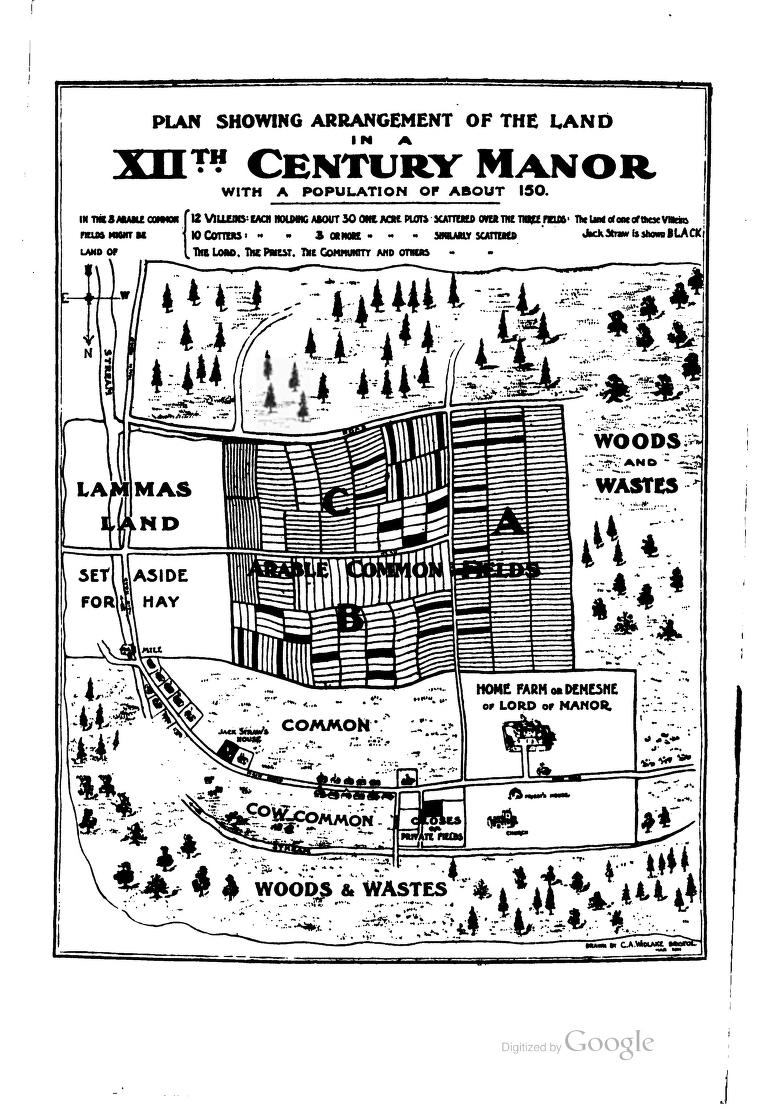

I discovered this amazing map in Montague Fordham’s book, “A Short History of English Rural Life from the Anglo-Saxon Invasion to the Present Time” published in 1916. (It’s amazing what you will find on ForgottenBooks.com.) I’ve recently come to the conclusion that any study of the Middle Ages is incomplete without getting your hands around the concept of the English Manor—and I will be the first to admit that my knowledge is sparse! I’m not writing this article as an expert—merely as a student of history.

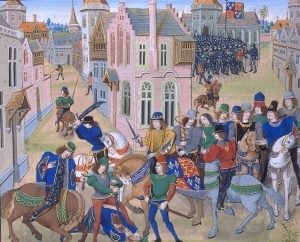

I was introduced to the complexity of this subject when I recently read the book “Life on the English Manor” written by H.S. Bennett and first published in 1937. This was a very difficult volume to plow through (so to speak), and I don’t think I did it justice. Having finished the book with great relief I immediately shoved it back onto my shelf, but I’ve been fretting over it ever since! So here I am again, and I am going to attempt to pull out the major points so I can get things straight in my own mind, supplemented by what I’ve learned from Fordham (of the map). After all, I’m currently researching the Peasant Rebellion in 1381, and guess what led up to it? It’s only 30 years away from the Black Death, and the peasants were still struggling against the impositions from their betters, trying to keep them from taking advantage of their improved situation. But for the most part, these articles will concern manors before 1350.

The smaller manors contained about 20-30 acres, though others included many villages; the Bishop of Winchester’s Manor of East Meon in Hampshire was 24,000 acres. But this is the exception. Apparently the average manor contained one village and was separated from the next manor by a broad stretch of woods or wasteland. Sometimes two manors split the same village in two. All manors contained a Home Farm (or Demesne), where you would find the hall and barns belonging to the lord; outside of this you would find a mill, a church, the priest’s house, then the village houses, and of course the fields. The lord would probably stay there a month or two during the year; the rest of the time, the bailiff or seneschal would reside at the hall.

The smaller manors contained about 20-30 acres, though others included many villages; the Bishop of Winchester’s Manor of East Meon in Hampshire was 24,000 acres. But this is the exception. Apparently the average manor contained one village and was separated from the next manor by a broad stretch of woods or wasteland. Sometimes two manors split the same village in two. All manors contained a Home Farm (or Demesne), where you would find the hall and barns belonging to the lord; outside of this you would find a mill, a church, the priest’s house, then the village houses, and of course the fields. The lord would probably stay there a month or two during the year; the rest of the time, the bailiff or seneschal would reside at the hall.

To look at this map, we see that the arable common fields were divided into sections called furlongs, shots, or dells. Each furlong was subdivided into little strips, or selions, which were separated by unploughed ridges called baulks. These strips were usually 1/2 to an acre of land, belonging to the peasants (sometimes the lord held some strips as well). A peasant often held more than one strip but they were not contiguous; an example is shown by the black colored-in holdings all belonging to Jack Straw. He must go to the end of his strip and walk on the headlands—more unploughed baulks perpendicular to the furroughs—to get to his other strips of land; the headlands were also where he turned his plough. Presumably the planting was a communal activity, though nothing is really known for sure. Apparently the reason a peasant’s holdings were scattered was the continual division between relatives and children. Bennett gave us an example from the Norfolk manor of Martham: “the 68 tenants of Domesday time had increased by 1291 to 107—a not unnatural growth—but, quite unexpectedly, subdivision had progressed so enormously that the land formerly held by the 68 had been split up into no less than 935 holdings in some 2000 separate strips.” Keeping track must have been a challenge.

If a peasant was lucky, he was permitted to rent, on a yearly basis, a few-acre patch of uncultivated “waste” land, usually on the border of the forest. This was called his “assart”, and he could plant on it what he pleased; it was often a godsend if the man had extra mouths to feed. The wastes satisfied other needs as well; they were used for grazing, and if wooded they provided fuel and wood for farm implements and repairs. Commonly, the peasant was allowed to take wood off the ground or “by hook or by crook”—whatever he could knock off a standing tree.

As best as I can determine, the wastes and the common area around the village is where the animals grazed while the crops were growing. The Lammas Land, or Meadows as they were called, were held in common, guarded, fenced around the outside, and planted between Christmas and Lammas (Aug. 1). When the crop was harvested, the Lammas Land was thrown open for grazing to the community.

I will be following up with more on the English Manor as I sort it out. The most important thing I learned is that there was no consistency from region to region or even from manor to manor. As Bennett put it, if a village was divided up between two manors, “it was possible for two men to be living in the same village, and each holding the same amount of land; but, because they served different lords, they might find themselves very unevenly burdened with services and rents.” So, of necessity, anything we learn about the Manor can only be seen as representational of the medieval peasant’s life. (see Part 2)