The battle of Stamfordbridge is well-known as the turning point in King Harold’s fortunes. But if it wasn’t for a lesser known battle that had taken place just a week before, Harold might not have fared as well: the Battle of Fulford was fought with great loss of life on both sides. And Harald Hardraada was the winner, though his forces were somewhat depleted. In a year packed full of great events, the Battle of Fulford seems to have sunk into obscurity, yet its importance cannot be underestimated.

Fulford is, very literally, a ford on the River Ouse just south of York. There may or may not have been a village nearby that found itself to be the host of an unwelcome invasion of Norsemen. They sailed up the Humber to the Ouse and finally anchored their fleet of 300 ships at Ricall a short march away. Because the invaders started at Scarborough and pillaged their way south, Earl Morcar of Northumbria and his brother Edwin of Mercia had enough notice to assemble their armies and block the way to York, though many said later that they should have waited for King Harold to arrive.

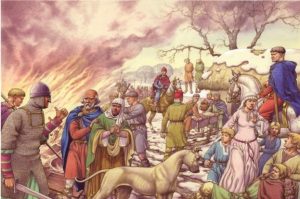

The ford was Morcar’s choosing, with good ground on the defenders’ side and marsh on the other side of the river. The Anglo-Saxon army lined up their shield wall about 1000 men wide and five ranks deep, facing about 6000 Norsemen, including Tostig and his small force. Around mid-day the invaders launched their attack, crossing the ford and assaulting the shield wall in many places.

Eventually, the English were drawn downhill and across the river, and as the fierce fighting continued for hours, the wily Hardraada managed to send a sizeable contingent secretly around Morcar’s flank. Suddenly the Northumbrians found themselves beset on three sides, and the shield wall started to break down as men were forced to turn and defend their rear. The English were forced to retreat – Edwin back to York, and Morcar east toward Heslington. The Norse had won the day, though loss of life was considered exceptionally high, even for such a violent age. It was said that the English had lost a third of their men, and the Norwegians at least a quarter.

Harald Hardraada and Tostig entered York but did not sack the city; Harald had come as a conqueror, not a marauder. The city came to terms and agreed to exchange 150 hostages with Harald. The ensuing four days were taken up with caring for the dead and wounded, repairing weapons and armor, arranging hostages and preparing for York’s formal submission to its new ruler. On the fifth day after Fulford, Harold Godwineson burst upon the scene, taking Hardraada totally by surprise at Stamfordbridge. Had the Norwegian king been less complacent and more prepared for battle, things might have gone differently.

If you’d like more information on this battle, there is an excellent book called The Forgotten Battle of 1066 Fulford by Charles Jones.