While doing research for my medieval romance, The Red Wolf’s Prize, I discovered some interesting things about the dietary habits of those living in England at the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066. To my surprise, they ate quite well and, for the upper class, their diet was quite varied.

While doing research for my medieval romance, The Red Wolf’s Prize, I discovered some interesting things about the dietary habits of those living in England at the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066. To my surprise, they ate quite well and, for the upper class, their diet was quite varied.

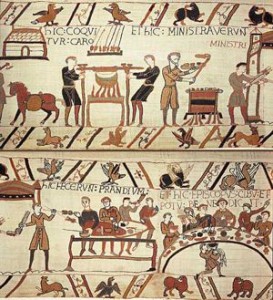

If you were to accept an invitation to dine in the manor house of a Saxon thegn, what you might be served would depend on where in England you were. Wild boar lived in the forests even to the 12th century, as did deer. Your main course could thus be roast venison or boar. There were also game fowl and other birds. If you were in sheep country, depending on the time of year, you might have roast lamb. Meat would have been served more in summer and autumn when domestic animals were killed and game was more readily available, although pigs, sheep and cattle were killed during the winter as well in order to provide fresh meat.

If your thegn lived near a river or the sea, you might be served fish or shellfish. A wide variety of fish was eaten, including herring, salmon and eel, as well as others not eaten as much today such as pike, perch and roach. It is also thought that they ate flounder, whiting, plaice, cod and brown trout. Shellfish, especially oysters, mussels and cockles formed a part of the diet for those with access to them. Fish was eaten fresh, but also preserved for less plentiful times of year. It could be salted, smoked, pickled or dried.

Since the fork was not invented then, you’d be eating your dinner with a spoon and knife. Even women had their own eating knives with sharp blades that could spear a tasty bit of venison.

Of course, there would be bread. They grew wheat, rye, oats and barley: wheat for bread, barley for brewing and oats for animal fodder and porridge. Sometimes a lord’s rent was paid in leavened bread. But even the grains varied by location. Wheat made the finest, whitest bread but it was not grown everywhere. If you were in Southern England, where the main cereal crop was wheat, your bread might be wheat or mixed grains, but in the north, where oats were grown for their weather resistance, you might be served oat-based breads and cereals at certain times. And you’d have butter on your bread. Milk, especially sheep’s and goat’s milk, was used to make butter and cheese.

Eggs from chickens, ducks and geese would also have been eaten although the fowl of the period would not have laid as those of today and the eggs might have been smaller.

Your meal would also be accompanied by vegetables grown in the kitchen garden or on the surrounding farms owned by the lord of the manor. It is known that they had carrots, but these were not the large orange vegetables that we eat today. They were closer to their wild ancestors, purplish red and small. Welsh carrots, or parsnips were also available. Cabbages were of a wild variety, with smaller tougher leaves. And they cultivated legumes such as peas and beans. So, a rich array was available.

If the meal was of the more ordinary variety, you might be served a hearty stew. Peasants ate soups and stews and used meat for flavoring. Such a stew might contain wild root vegetables such as burdock and rape, and onions and leeks, even wild garlic.

Spices were available, so your meal wouldn’t be bland. In Aelfric’s Colloquy, the merchant speaks of importing spices. Food imports were moved around the coast and up the rivers by barge and boat. Depending on your thegn’s location, among the spices used on your food might be ginger, cinnamon, cloves mace and pepper. In Bald’s Leechbook, broths of mint and carrot and ginger, peas and cumin are mentioned.

Salt was a precious, expensive commodity produced from evaporation from seawater and from salt springs in Worcestershire and Cheshire (near where The Red Wolf’s Prize is set). You may recall the Middle Ages expression “below the salt,” which refers to those lesser beings who sat below the place in the table where the salt was placed.

To drink, there would be ale, apple wine and honey mead wine served, most likely, in wooden or pottery cups and mugs, though there is no evidence of handles on these. Horns were also used. After the Conquest, if not before, you might be served wine imported from Normandy or other parts of France.

Dessert might be a healthy affair: apples, pears, quinces, cherries, grapes, peaches and berries—in season and in locations where they were grown. They did have honey as a sweetener, too, and almond cakes were popular though not served every day.

Much of Anglo-Saxon life changed with the coming of the Normans in 1066. For one thing, the new Norman lord owned all the forests and could deny access to the game. The Saxons who were once freemen became virtual serfs. With 5,000 knights to feed, William the Conqueror was quick to claim resources for himself, thereby depriving the English population of the rich diet they once had.

Bestselling author Regan Walker loved to write stories as a child, particularly those about adventure-loving girls, but by the time she got to college more serious pursuits took priority. One of her professors encouraged her to pursue the profession of law, which she did. Years of serving clients in private practice and several stints in high levels of government gave her a love of international travel and a feel for the demands of the “Crown” on its subjects. Hence her romance novels often involve a demanding sovereign who taps his subjects for “special assignments.” In each of her novels, there is always real history and real historic figures.

Regan lives in San Diego with her golden retriever, Link, whom she says inspires her every day to relax and smell the roses.

www.reganwalkerauthor.com

Regan Walker says:

Hi, Mercedes! Thanks so much for having me and the Red Wolf on your blog! I’m glad to be here sharing the foods the Saxons ate!

Regan

wendy butler says:

Would you be willing to share your resources regarding foods and recipes used during this period in history? I would be most grateful. Thanking you in advance. Wendy Butler

Collette Cameron says:

What a fascinating post, Regan.

Regan Walker says:

Wendy, I don’t have any period recipes (they didn’t leave any), but you can see my attempt at one on my website here: http://www.reganwalkerauthor.com/maggies-mutton-lamb-stew.html. As for my food research, it’s pretty much here as far as The Red Wolf’s Prize goes–and it’s reflected in the novel. I also use the book The Art of Dining, a history of cooking and eating by Sara Paston-Williams. Hope this helps.

Regan Walker says:

So glad you enjoyed the post, Collette!