The year 2016 marked the 1000th anniversary of Canute’s coronation as the King of England. I think it’s interesting that even though the Danes ruled all of England for more than a generation, very few moderns seem to give it any thought at all. Between Canute and his sons, the Danes were kings from 1016 through 1042, yet we still think of England as Anglo-Saxon during that era.

Of course, the Vikings were no strangers to England. During the reign of Alfred the Great, the Danes overran the country and would have conquered but for the dogged resistance of the King of Wessex. In the end, Alfred the Great divided the country in half, and the Northmen settled and ruled the Danelaw for the next 200 years. By the time Canute’s father, Swegn Forkbeard took the crown in 1013, England’s Aethelred the Unready had made such a mess of things that the country was beginning to think that Danish rule might be preferable after all. Not that they had much choice.

Swegn Forkbeard died suddenly in 1013, having ruled for only a few months. Aethelred’s son Edmund Ironside had a brief tenure as king, constantly harassed by the Danes under Canute, who was the second son of Swegn (his older brother Harald ruled Denmark until 1018). Ultimately, Edmund Ironside and Canute agreed to divide the country so that Edmund would rule Wessex and Canute the rest of England; if one died, the crown would devolve to the survivor. Alas, the end result was all too predictable.

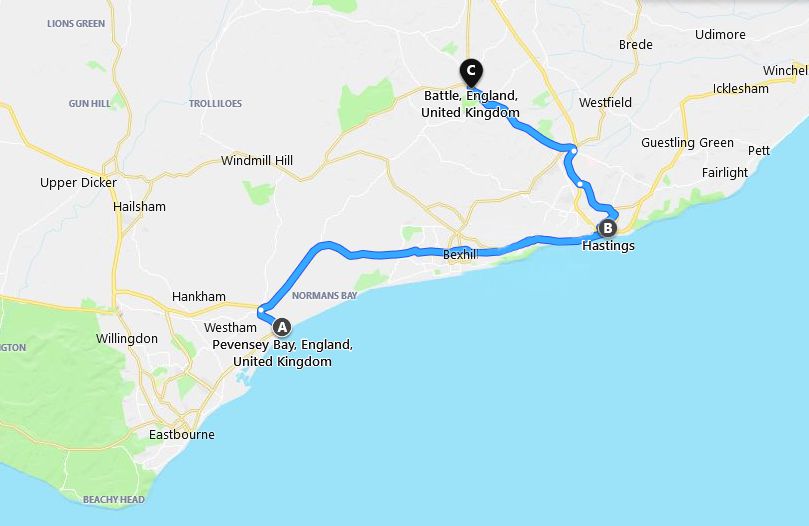

It was conjectured that Edmund Ironside may have been murdered by the villanous Eadric Streona who seemed to change sides like most people change their clothes. But whether by foul means or natural causes, Edmund did not survive his first winter as King. Canute took over in 1016 and at first things didn’t look good for the Anglo-Saxons. Some key english Thegns were assassinated (including Eadric Streona) and Viking Jarls installed in their places. Canute proceeded to raise the largest Danegeld tax yet (£82,500) to pay off the Viking ships, but luckily he sent most of the army home afterwards. From then on, England was not considered fair game (except for the occasional raid) until the unhappy events of 1066.

Historians often voice their surprise that Canute decided to settle down and adopt the ways of his conquered people, in direct contrast to William the Norman. I think it could be fairly said that the Danes were absorbed by the Anglo-Saxons through intermarriage and common economic concerns. Although Canute had difficulty juggling his Empire of Denmark, England, Norway and part of Sweden, he made England his home. He presided over 20 years of peace and prosperity, and by the end of his reign, Canute was known as a good and just king. Had he not died young – only about 40 years old – England might have stayed Danish considerably longer.