Before I even realized Historical Fiction was a genre, I was fascinated with MACBETH and the witches’ prophecy. If you recall, after they told Macbeth he would be king hereafter, Banquo wanted to know what they had to say about his future. They answered:

Before I even realized Historical Fiction was a genre, I was fascinated with MACBETH and the witches’ prophecy. If you recall, after they told Macbeth he would be king hereafter, Banquo wanted to know what they had to say about his future. They answered:

“Lesser than Macbeth, and greater.”

“Not so happy, yet much happier.”

“Thou shalt ‘get kings, thou be none.”

Just what kings were they talking about? And what happened to Fleance after he escaped from Banquo’s murderers? I can only suppose Banquo’s legacy was common knowledge to the Elizabethans, for Shakespeare dropped the Fleance subplot, leaving later generations to puzzle over its meaning.

Shakespeare’s story of Macbeth, taken from Raphael Holinshed (who took it verbatim from Hector Boece 1465–1536), was a legend, not real history. Macbeth did NOT kill King Duncan in his bed; King Duncan was killed in battle. In fact, Macbeth was considered by historians to be a good king who reigned fourteen years. But really, who would want to give up such a juicy tale?

I knew none of this at the time—when I started this novel a good 35 years or so ago (some first novels take a long time to mature). In the early ’80s—when the internet wasn’t even a twinkle in Al Gore’s eyes—I only had access to books in my local libraries, and in St. Louis that was a severe handicap. Once I moved to New York and discovered the NY Public Library, my research venue improved considerably. I was surprised to discover that Banquo was thought to be the ancestor of the Stewarts, and James I had only mounted the throne of England a couple of years before this play was written. Shakespeare was giving a nod to James I’s ancestry—and his work on demonology—while showing his audience that killing the king was a really bad idea. It wasn’t until much later—only recently, as a matter of fact—did I discover that MACBETH was written in response to the gunpowder plot of 1605. As it turns out, Shakespeare’s family had some disconcerting connections to the conspirators, and it is thought that the great bard wrote Macbeth to clear himself of any guilt-by-association; the play was first performed nine months after the gunpowder plot was foiled.

But I digress…

As it turns out, connecting Banquo to King James Stewart was the whole purpose of the witches. So when the weird sisters told Banquo “Thou shalt ‘get kings”, they were talking over 500 years into the future! The witches, such an integral part of the play, were already embedded in Shakespearean society; much of that can be attributed to King James (also James VI of Scotland) who was pretty much responsible for the witch burning craze that infested Scotland in 1597. To this day I still don’t understand why this would be a good plot device for Shakespeare. In fact, it is popularly thought that James was so displeased he banned the play for five years, though I can’t find any credible documentation to support this speculation. However, it has also been suggested that the weird sisters (or wyrd sisters) were a manifestation of the Norns—the Norse goddesses who controlled our destiny, much like the Greek Fates. What did Shakespeare have in mind? Considering that paganism was alive and well in the 11th century, it’s not really all that far-fetched. And indeed, this is the interpretation I chose for my novel. It was the Norns who set up a chain of events that placed the Stewarts on the throne. It made so much sense to me!

I discovered a history called Cambria Triumphans, written by Percy Enderbie in 1661; it referred to the old legend, and from this came the plot of my novel. He told us about Fleance and “during his residence in the Welsh court, he became enamoured of Nesta, the daughter of Gruffydd ap Llewelyn; and violating the laws of hospitality and honour, by an illicit connection with her, she was delivered of a son who was named Walter.” Aha! I struck gold. Little did I realize (until I was deep into my research) how many historical figures were actually related to Walter; on his mother’s side he was grandson of Gruffydd ap Llewelyn, Prince of Wales and Ealdgyth, daughter of Aelfgar, Earl of Mercia (and future queen of England); on his father’s side he was grandson of Banquo. He was a distant relation to Alain le Rouge, Count of Brittany and future Earl of Richmond. And, to fulfill his destiny, Walter was created the first Steward of Scotland, a hereditary post. Walter’s quest to unravel his legacy took him through many historical events like the Battle of Dunsinane, the Battle of Hastings, and Malcolm III’s court, and gives us a rare look at eleventh century Scotland as well as King Malcolm’s relationship with William the Conqueror.

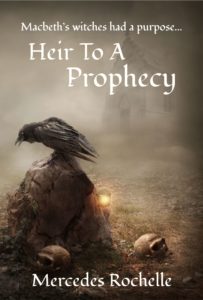

I hadn’t planned to write a historical novel, but by the time I figured it all out, my course was already charted. While researching this book I became fascinated with Earl Godwine and his family, which inspired me to write my “Last Great Saxon Earls” trilogy. All three books overlap this one, and Walter even makes a cameo appearance in “The Sons of Godwine”. This year I was able to regain my rights and publish a revised edition of “Heir To A Prophecy”. It was great fun to revisit my old friend.