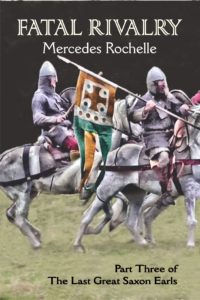

In 1066, the rivalry between two brothers brought England to its knees. When Duke William of Normandy landed at Pevensey on September 28, 1066, no one was there to resist him. King Harold Godwineson was in the north, fighting his brother Tostig and a fierce Viking invasion. How could this have happened? Why would Tostig turn traitor to wreak revenge on his brother?

In 1066, the rivalry between two brothers brought England to its knees. When Duke William of Normandy landed at Pevensey on September 28, 1066, no one was there to resist him. King Harold Godwineson was in the north, fighting his brother Tostig and a fierce Viking invasion. How could this have happened? Why would Tostig turn traitor to wreak revenge on his brother?

The Sons of Godwine were not always enemies. It took a massive Northumbrian uprising to tear them apart, making Tostig an exile and Harold his sworn enemy. And when 1066 came to an end, all the Godwinesons were dead except one: Wulfnoth, hostage in Normandy. For two generations, Godwine and his sons were a mighty force, but their power faded away as the Anglo-Saxon era came to a close.

Available in Paperback and Kindle: http://a.co/838SFLc

Geoffrey Tobin says:

As I think I have noted, Tostig’s wife Judith of Flanders was a first cousin of Duke William’s. One would naturally think she’d be related to his wife Matilda of Flanders, but she wasn’t, except by marriage. Judith was named after her grandmother Judith of Brittany.

Tostig’s widow married Welf I, Duke of Bavaria, and is thus an ancestor of that widespread Imperial dynasty, which includes Queen Victoria. The Welfs are a branch of the Frankish house of Este, originating with Margrave Adalbert of Mainz in 951, coincidentally 1066 years ago.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

My real reason for writing is that I have been studying the Bayeux Tapestry in conjunction with other documents of that generation. After some struggling to figure it out, I’ve twigged to where the Breton knights are in it: they’re the ones bearing white shields with a simple pattern of dots. (I guess ermine spots are too fine a detail for the embroidresses to achieve convincingly.)

Edward the Confessor’s funeral is watched by an unusually-realistically drawn elegant red fox in the lower border. I think this is a rebus for Alan Rufus, whose name means “the red fox” in colloquial Breton, which Abbot Scolland would have known.

Since it’s very probable Alan Rufus was the royal thegn (“Comes”) Alan of Wyken in Suffolk, the BT is implying that he was excluded from participation in the funeral of his royal relative, but did not leave England until afterwards.

It looks very much as though Harold Godwinson dismissed Alan from his post.

Had this not happened, Alan would have felt himself obliged to serve King Harold. How much difference this would have made is evident in the panel of the BT where Earls Leofwine and Gyrth are overrun by Breton knights.

Since Alan received as many of Gyrth’s manors as King William did, it’s pretty clear that he led those knights.

The Carmen asserts that when William’s horse was axed, Gyrth attempted to slay him, but William defeated him in single combat.

Domesday has Gyrth’s most valuable manor going to William de Braose, so most likely it was he who dealt the fatal blow.

The BT shows an Englishman clad in mail axing the neck of a horse ridden by the leading Breton knight on the right. As he does this, another armoured man touches his arm to attempt to draw attention to the foot soldier about to stab him in the back with a spear. The axed horse is shown on its head, presumably in death agony, while someone attempts to control it using the reins.

I think here we may have a depiction of Gyrth axing Alan’s horse and William de Braose spearing Gyrth. Alan would have insisted that de Braose be rewarded with the finest prize for this.

Coincidentally, it was a later William de Braose, Fourth Lord of Bramber, who spilled the beans on King John’s murder of Prince Arthur.

Geoffrey Tobin says:

In the Bayeux Tapestry scene I identify as of Earl Gyrth’s last moment alive, the white shield held by the rider on the black stallion has a pattern twelve black spots. I take this as indicative of rank: Duke William’s shield has a large cross with twelve spots in similar arrangement. Other officers are shown holding shields with fewer spots.

The twelve-spotted white shield appears earlier, held by the chief guard behind Harold’s nephew Hakon in William’s palace. The guard has yellow hair and wears an orange tunic with yellow v-neck and yellow belt.

An identically dressed figure is present in many other scenes. He is one of William’s envoys to Count Guy of Ponthieu, and is riding a familiar black stallion; this horse is one of those tended by Turold, and its rider stands beside him.

When Harold swears his notorious oath, this figure looks at Bishop Odo and points to the word “sacramentum”, but Odo seems to be shushing him.

At the Norman “Last Supper” near Hastings, we recognise the man standing beside the Bishop and pointing to the name “Odo”.

James Edmundson says:

Hello. My Edmundson family has been traced back to old Westmorland, England around Little Musgrave. I also find a lot of Edmundsons around York. I speculate that I descend from Harold Godwinson via one his sons Edward or Edmund. Any thoughts on how to trace back from my last confirmed ancestor, Willliam Edmundson, b. 1627-1712. I have tried for years but don’t know how to proceed. Thank you, James E. Edmundson.

Mercedes Rochelle says:

Hi James. Geneaology is not one of my strengths, unfortunately. You might contact Geoffrey Tobin, a frequent contributor on this blog: you can find him on Twitter @grdtobin. He has an encyclopedic knowledge of the period. Good luck.