It wasn’t until recently that I discovered that Trial by Combat, at least in the 14th century, was a strictly regulated function of the Court of Chivalry, which was the household court of the constable and marshal of England (also known as the Curia Militaris, the Court of the Constable and the Marshal, or the Earl Marshal’s Court). In Richard II’s day, the position was held by Thomas of Woodstock, the Duke of Gloucester and the King’s uncle. He even wrote a treatise on the duties involved with this office.

In court, if evidence in an appeal (accusation), whether of treason or any other offense, was insufficient or unprovable—no witnesses, for example, nor tangible evidence—the case would often be settled by judicial battle. (As far as I can determine, this is the only circumstance where Trial by Combat was invoked.) Some think of this as a precursor to the duel (of honor) fought in later centuries. The most famous trial by combat in the fourteenth century was between Henry of Bolingbroke (the future Henry IV) and Sir Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk. Of course, the combat never took place; the King stopped it at the last minute. But the ceremony and protocol were all there; we get a colorful description in the Chronicque de la Traison et Mort de Richart Deux Roy Dengleterre (the author was probably an eye-witness).

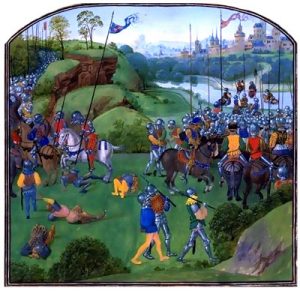

The tournament, to be held at Coventry, was announced far and wide. It was the event of the year; the Duke of Albany’s son came from Scotland; the Count of St. Pol and other nobles came over France. Preparations were extensive; the King’s armory was placed at their disposal. Bolingbroke was sent armorers from the Duke of Milan, and Mowbray engaged armorers from Germany or Bohemia.

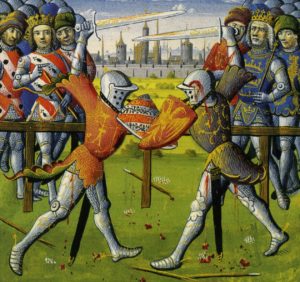

According to la Traison, “The lists were to be sixty paces long and forty wide; the barriers seven feet high. The sergeants-at-arms were not to let the people approach within four feet of the lists… the penalty for entering the lists, or making any noise, so that one party might take advantage of the other, was the loss of life or limb, and also of their castles, at the pleasure of the King.” This was serious stuff! Bolingbroke entered the lists on a white charger followed by six or seven knights on white horses, his was caparisoned in blue and green velvet embroidered with swans and antelopes. Mowbray’s horse wore crimson velvet, embroidered with lions of silver and mulberry trees. There was an exact wording the contestants were required to state (I remember it well in Shakespeare): Bolingbroke said, “I am Henry of Lancaster, Duke of Hereford, and am come here to prosecute my appeal in combating Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk, who is a traitor, false and recreant to God, the King, his realm, and me.” The constable opened Henry’s visor to determine he was the man he supposed to be, “the barrier was then opened, and he rode straight to his pavilion, which was covered with red roses, and, alighting from his charger, entered his pavilion and awaited the coming of his adversary.”

At this point, the King arrived, accompanied by a great retinue. Once they were settled, his herald announced, “Oez, oez, oez… It is commanded by the King by the Constable, and by the Marshal, that no person, poor or rich, be so daring as to put his hand upon the lists, save those who have leave from the King and council, the Constable, and the Marshal, upon pain of being drawn and hung… Behold here Henry of Lancaster, Duke of Hereford, appellant, who is come to the lists to do his duty against Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk, defendant; let him come in the lists to do his duty, upon pain of being declared false.” At once, Mowbray came forward and swore the same oath as Bolingbroke then went to his own pavilion. The constables measured the length of the lances and the two squires presented them to their knights. According to la Traison, “The weapons allowed by the marshal and constable were the “Glaive”, long sword, short sword, and dagger. The long sword was straight, and called by the French “estoc”, whence estocade, a thrust.” The King ordered that they take away the pavilions and “let go the chargers, and that each should perform his duty”. Apparently Bolingbroke first advanced a few paces when the King threw his threw his staff (warder) into the list, crying, “Ho! Ho!”

For the King to interfere in the duel was not unheard of, though it seems that the crowd was bitterly disappointed to be denied their entertainment; never mind that the fight was to the death. Apparently there were no other amusements on the agenda. The contestants were equally skilled in tournament fighting, and by no means was the result a foregone conclusion. The king withdrew with his council—including Bolingbroke’s father, John of Gaunt—and discussed the matter for two hours while the attendees waited. Finally it was announced that Bolingbroke was to be exiled for ten years and Mowbray for life. From most accounts, the crowd was incensed at Bolingbroke’s treatment; after all, he had done nothing wrong. Few seemed to object to Mowbray’s fate; was he guilty until proven innocent? Nonetheless, everybody went home unhappy, not least of all the main contestants. Both were promised large annuities and given a few weeks to put their affairs in order.

Trial by combat seems to have died out by the 15th century, and I haven’t found anything quite as dramatic as this contest. The amount of preparation for such a non-event is staggering. If you happened to be versed in medieval French, you can learn more about tournament ceremonies in this book, reproduced in Google Books: “Ceremonies des gages de batailles selon les constitutions du bon roi Philippe de France”.